Prefer to Hear this Story Instead? Listen Here.

Here’s something you won’t read about on the tourism websites: being afraid of the desert.

It’s something that’s never really registered with me, but there sure are an awful lot of people who are absolutely uninterested in venturing beyond the cell phone towers, hundreds of miles from signs of civilization in every direction even though in Nevada, that sort of isolation comes along with just about everything you do, everywhere you go. Where I search for this very special kind of solace most people are afraid, and we’ve got folks like ol’ Bristlewolf to thank for it. A Nevada legend, but in all the worst ways.

For years and years, my husband and I used to scour maps in search of every last sign of a new-to-us hot springs source in Nevada. We planned our entire lives around it (which sounds dramatic but is honestly a basic truth) spending every spare second we could in search of the next great soak. Usually there is an unreplicated thrill in rolling up on a hot springs pool for the first time, where you’ll find the source and then hopefully a perfectly maintained pool somewhere nearby, and visiting Pinto Hot Springs for the first time back in 2015 was no exception.

A feeling of excitement that was then immediately followed by, “wait, something definitely feels off around here.” We didn’t have time to soak or really even explore the grounds beyond that main, cerulean pool that day, but after returning to civilization and pinging cell phone towers we discovered our intuitions weren’t wrong—three people were murdered at Pinto Hot Springs by a desert recluse who emerged from his underground hovel and shot them. People who were out roving Nevada’s high desert public lands, just like us.

The Great Basin Desert: In Search Of __________

There are a lot of reasons people head out into the Nevada desert. Depending on where you’re at, the Great Basin’s unending sea of sage affords some of the most isolated terrain in the Lower 48 states, while other times you can be mere miles from a metropolitan area, city, or town and be completely hidden in plain sight and undetected just the same. As a human race, at least in the last few hundred years or so, I think it’s safe to say that we turn to open spaces in a way only the West can afford in times of solace and crisis alike, with an infinite list of reasons that can be as complex as the Nevada landscape itself.

For me personally, I know I’ve disappeared in the Great Basin Desert during times of personal crisis as a way to run from bad behavior while searching for answers to help recover from it. I’ve also sought freedom-seeking thrills only attainable in Nevada borders that range from unbeatable human connection, recreational spectrums beyond my wildest dreams, and even deep spiritual connection. I want to learn and experience it all as a way of immortalizing the stories of the Nevadans before me while adding my own. The common denominator throughout that trajectory? To protect my peace and find myself at once.

But I’m definitely unalone there. This is the narrative for most people I’ve crossed paths with in Nevada to varying degrees—whether it’s weekend voyagers like me, or people who’ve uprooted their lives and made Nevada’s fabulous faraway terrain their home. Most Great Basin believers are searching for their own personal freedoms in one way or another, which can range from anything’s-possible-American-Dreamin’, to hiding from the government or some other sort of enemy, to simply not wanting to be told what to do or how to live their lives from anybody else, or even more drastically, they’re searching for total and complete isolation. In Ronald Bristlewolf’s case, the reasons he decided to disappear in the Nevada desert were all of the above.

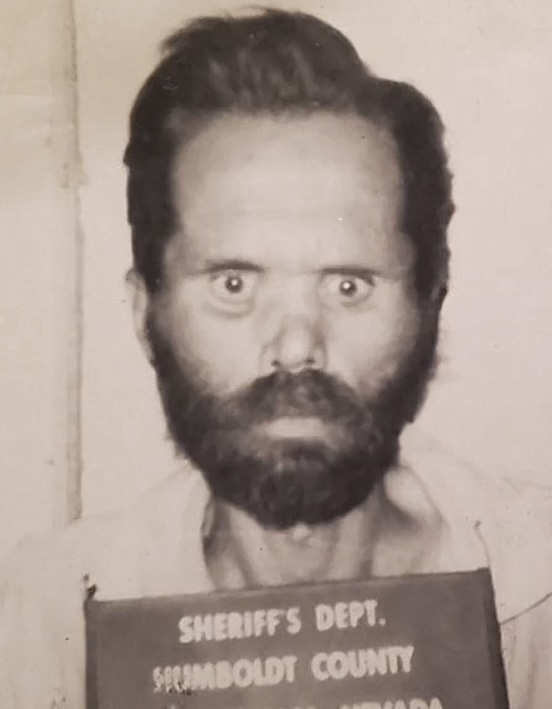

Becoming Ronald Bristlewolf, Nevada’s “Homicidal hermit”

From what I can gather from an absolutely erratic array of internet search results, Ronald Gress was always a bit of a misunderstood cat, working a string of odd jobs while trying to stay away from societal norms and everyone else because he knew that was the only way he could survive. He certainly succeeded—that is until a few unlucky souls got a little too close, where he would emerge from his underground 2-room hovel and murder three people in the Black Rock Desert in 1978.

Ronald Gress had made a life for himself drifting from one abandoned place to another across (think old ghost town ruins and even abandoned cars) the American West, slowly becoming more and more disconnected with reality and conventional society with each move and respective capture. You can get a glimpse of his unfortunate pattern by watching a docuseries-in-progress over on YouTube under the channel Bristlewolf, where (at least as of this writing) a couple of retired Oregon state policemen describe running Gress out of an old abandoned structure for squatting and poaching. Ronald Gress would be captured many times similar in nature to this standoff-style arrest, sent to jail where he was treated with medication and therapy before eventually being discharged on work release.

But after this last confrontation with Oregon’s boys in blue, he made his way south into the Nevada desert near Denio, NV. A teeny-tiny place on the Nevada-Oregon border where he would become Bristlewolf.

To backtrack for a sec—it’s no secret that Nevada beholds more public lands than anywhere else, with a figure like 80% open to the general public to do just about whatever you want, whenever you want to do it. Today you can roam Nevada’s public lands for free (at least in most cases where you don’t need a special caving or prospecting permit), with one caveat: the federal government requires that you don’t stay in one place for longer than 14 days maximum. The way I understand it, this regulation is in place so people don’t make a permanent or even semi-permanent living situation out there on federal lands, for free. But back then in the 1970s when Ronald Gress was looking to get away from everyone, no such 14-day rule existed.

After too many run-ins with the law, even a tiny town with only a few dozen residents was too much for Gress, so he slipped back into his pattern of retreating to remote and abandoned places to live. And as the driest state in America, what better place to live than next to flowing natural hot springs and a reliable water source? Tucked into the high desert hills about an hour from Denio, Gress lived a true survivalist’s lifestyle in northwestern Nevada, living off the land mostly eating jackrabbits or other animals struck by cars. He loved animals and feared people, and really despised killing animals he needed for food and mostly avoided it. Area ranchers said he always carried a gun, and whenever he talked with somebody, he would raise the barrel a little just to make them squirm.

After living off the land in the most gruesome, unimaginable way for at least two years, Gress worked some sort of a small prospecting claim in the Quinn River area until he got into a bad accident where he blew up most of his right hand. Then he was able to claim a $185-a-month disability pension, which helped sustain a healthier lifestyle. It was during this time that he really adopted a second, made up identity—Bristlewolf—and area locals began referring to the hot spring he claimed as “Three Fingers Hot Spring”.

Pinto Hot Springs: A Desert Recluse’s Refuge

Living at a hot spring? Sounds equal parts dreamy and sustainable to me—there are even a few modern day hermits who live out at a few Nevada hot springs I know of that seem to do just fine—all the way up until the living-in-an-underground-dugout part. I guess you could say ol’ Bristlewolf was pretty resourceful—surviving a northwestern Nevada winter above ground would be pretty brutal, hot water or not. But right there next to Pinto Hot Springs, Bristlewolf dug an underground, two-room 8×10 foot home for himself accessed via ladder, surrounded by two gardens and an irrigation system he rigged up with the hot springs water.

Even though basically everyone in the region knew and feared him, things went pretty ok for Bristlewolf out there for a while. Locals never got too close to him, and of course the BLM’s 14-day rule didn’t exist yet so he could just keep on living there.

I came across a few different articles that suggested that he knew the federal government was looking at changing this limitless, stay-as-long-as-you-want regulation and Bristlewolf became paranoid about it, worrying that someone would come and try and kick him off “his” land, again. A gun wielding loose cannon living in complete isolation with increasing paranoia? That spells bad news to me, too. And people—unfortunately in this case that meant anyone—getting too close to Bristlewolf and Three Fingers Hot Spring cost them their lives.

Black Rock Desert Deaths

Welcoming desert explorers from all corners of the American West, the proprietors of the Denio Junction Motel didn’t think much differently of Colorado newlywed road trippers Richard and Judy Weese, up until they never returned to their room. The Weese’s—Richard, who was 40, and Judy, 31—decided to hit the road from Colorado to Nevada that summer to try and track down a gold mining claim they had inherited. Using Denio as their basecamp, they set off into the ruggedly remote northwestern Nevada corner searching for their freshly inherited claim, which led them right to Pinto Hot Springs.

Only Bristlewolf and the Weese’s know exactly what went down, but legend has it that they unknowingly arrived near “his” underground hovel, Bristlewolf became threatened by them in some way or another, and he met them with the wrong end of his rifle. To make matters worse, an old Basque sheepherder, Peter Chachenaut—who Bristlewolf knew and allowed to soak his arthritic legs at the hot springs regularly—arrived for a soak. Upon accidentally discovering the grisly murders, Bristlewolf emerged from underground and shot him too, then left the three victims out in the open and next to the hot springs for about a week or so.

The folks running the Denio Hotel knew something went wrong when the Weese’s didn’t return to their room, and reported them missing. Then two men who were in the Pinto Hot Springs area rockhounding, and lucky enough to remain undetected by Bristlewolf himself, reported seeing three bodies near the hot springs. When Humboldt County police arrived at the scene, Bristlewolf reportedly took off on a three-wheeler before being captured and sentenced to three consecutive life terms.

He was just 44 when he murdered those three people, and with a ruling he was mentally unfit to stand trial, lived the rest of his life in the Nevada State Prison system until he died in 2013 at the age of 78. What a wild tale.

Imagine our complete, bewildered disbelief reading these accounts after we’d been to this very public lands hot springs just hours earlier, knowing something about that place was off but not being able to put a (missing) finger on it. The terrain looked like Nevada hot springs in the old days—you know, before massive geothermal operations take over, and the powder-coated alkali ground is cracked open, exposing all kinds of flowing hot creeks and bubbling geothermal pools every spectrum of the color wheel with man-made geysers, even.

In other words, a total euphoria for the hot-springs-obsessed like us, where we were drawn to it like moths to a flame—or eh, maybe red spider mites to a natural bottomed pool. Something like that. And unknowingly, right beneath our feet and out of view was an underground room that played a part in a very sinister thread of Nevada history, just as undetectable a threat as it was that summer afternoon for the Weese’s. Even in the many trips back to Pinto and seeing evidence of underground rooms still there and having that “something’s off about this place” feeling still remain, I’m not sure I’ll ever be able to relax at Pinto.

While I refuse to let fear lead my Great Basin rambles and will loyally err on the side of awe now and always, I can’t say that experience didn’t make me think differently, even just for the space of that afternoon. In a place with unbridled possibility, I suppose it allows for the good and bad to mingle together, at least long enough for this Legend of Lost Nevada to earn his spot in the history books.