Prefer to Hear this Story Instead? Listen Here.

As far as I know it, there isn’t much a Nevada dirt road won’t fix.

I’ve spent a lot of hours this past year thinking about how people have moved across the West throughout time. About how most of the roads we follow in a modern world were forged by pioneers following old wagon trails and emigrant routes, and how those mimicked human migration paths an indigenous population steadily replied upon for thousands of years long before that. And even before then, it probably all began with some ancient creature humans chased after. It’s a wild thing to let your mind expand upon the next time you’re wondering why a road has that particular bend in it, that’s for sure.

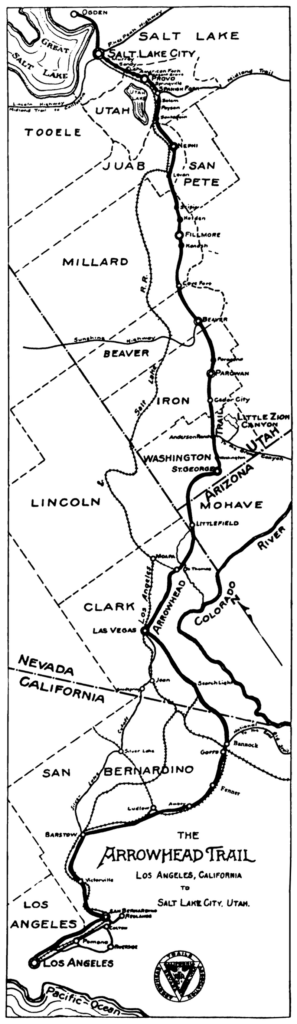

As the first all-weather road in the United States and the first ever scenic highway in Nevada, Utah, and the American Southwest, the 853 mile-long Arrowhead Trail is no different, closely following routes people have used for centuries, and before that, what the pros estimate to be the oldest prehistoric trackway the dinosaurs followed. But unlike the sensational tourist heralding route the powers in play wanted this state-bridging scenic drive to become, the mighty Arrowhead Trail is now not much more than an imagined route from another time. A Legend of Lost Nevada.

Seeing The West Unlike Ever Before

The West the world knows today sure is an iconic one, especially with Arches, Zion, Bryce Canyon, Gold Butte, the Valley of Fire, and the Grand Canyon luring you over this way. Its world-renowned prowess was first realized (at least in a modern world) by the turn of the 20th century, when the so-called sublime, or “untouched” and “pure” landscapes of the American West inspired folks like Henry David Thoreau and John Muir to persuade President Roosevelt to set aside some of these magnificent places for the long haul.

The Yellowstones and Yosemite’s of the world were then dedicated and preserved, which helped usher in the Great Western Awakening, or a time when seeing the West became the American thing to do, but only if you could actually afford to go on elaborate outdoorsy vacations and in a lot of cases, purchase or have unbridled access to early models of vehicles with “off-roading” capabilities.

Remember this was during a time when the grueling trek across places like Nevada’s Forty-Mile Desert were fresh in the minds of people having personally just endured it, and purposely going back to such inhospitable places of the American West was the insane thing to do—that is, unless you were cut from the upper crust. It was an era of American history that commanded elite easterners to swap their cosmos for Coors and high rises for cowboy campfire stew to embark on adventurous, “rugged living” out West.

During this same time, at the turn of the 20th century, early models of the Pierce Arrow were being tested on surreal landscapes like the Bonneville Salt Flats for its speed and off-highway capabilities, and the development of the Lincoln Highway (or Nevada’s Highway 50 and what would eventually be coined the Loneliest Road in America) opened as the nation’s first transcontinental highway, or an artery that spanned coast to coast. More than ever, this idea of not only exploring the now-available American West was burning bright and hot on the minds of many Americans, but traveling long distances from the comfort of your own personal vehicle (and not a shared locomotive) became more on hand than it ever had been before.

This was without-a-doubt an exciting time in American travel culture, and what’s even more fascinating and super-fun for me to think back on, especially when pointing my Tacoma down every last square inch of Nevada highways I can get my tires on, is this was also during the same period of when the Michelin Man really began being marketed to the masses. Besides a folk hero that made tires available to your brand new personal automobile, Michelin also initiated this absolutely genius marketing plan, where Americans were called to top-rated fine-dining Michelin Star restaurants scattered all across the country. Places that depended on good Michelin tires to actually reach and spread out far enough it, in many cases, meant buying a new set of tires to see what that one restaurant way off in California was capable of serving, and with a brand-spankin’ new American Auto Tour to check out along the way.

A Patriotic Hello to the American Auto Trail

Next, Motor Court Motels started to spring up all over the country, too. They’re the type of places I purposely seek out as I travel through Nevada (at least when I’m not public lands camping), because they’re usually under ownership of the same family through the decades and feature some really incredible retro signage of some kind that if you’re lucky, you’ll find the original neon buzzes on. Some of my favorites include the Scott Shady Court in Winnemucca and the El Rancho Motel in Boulder City, but rest assured this was an American movement with thousands of gloriously neon-ified motor court motels designed to accommodate a new rush of motorized travel throughout the nation. The American motor court trend was way into the future from the Arrowhead Trail, but does give perspective for where this whole thing was headed.

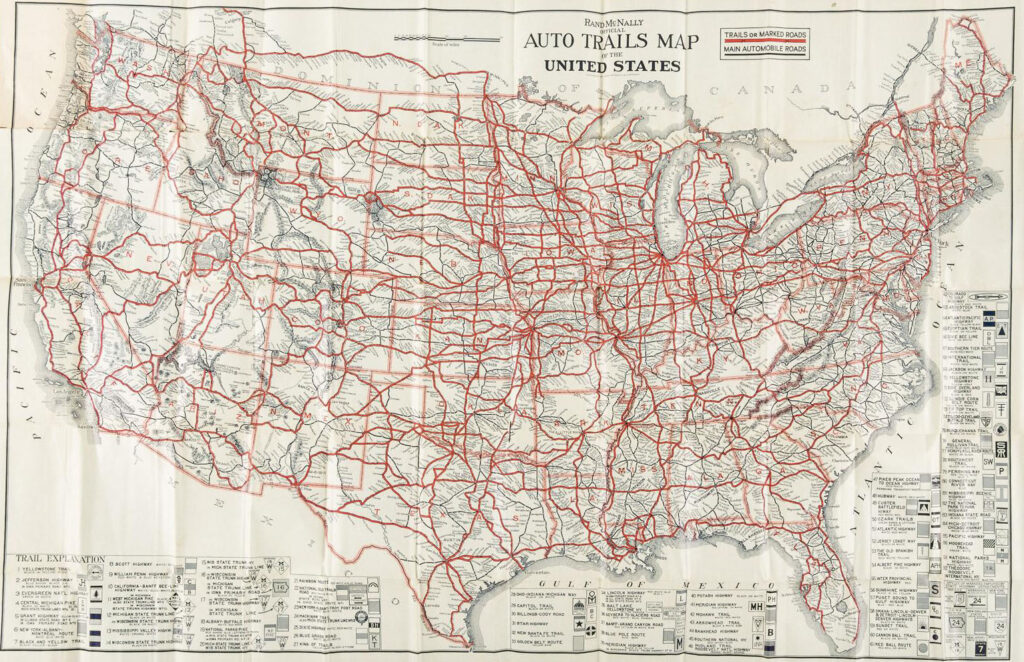

So by the time the 1920s rolled around, there was definitely tons going on with a lot of new travel trends born during this era that we still fully embrace today. With so much excitement surrounding conquering “new and unseen” landscapes of such iconic grandeur and enthusiastic access to tools that could take you there, the “Auto Trail Period” became a thing in the United States, which was a time that basically ushered in the development of lively informational routes across the country. So, think wonderfully themed highways that not only helped people navigate in the early days of the automobile, but also introduced highway systems with enough thematic gumption to keep you cruising a little further down the road to see what pleasantries might reveal themselves next.

Usually maintained by private organizations like localized chambers of commerce to anyone who showed up with “enough paint and the will”, the Auto Trails would eventually be replaced by the United States Numbered Highway System (so think Interstate 80, or Highway 101 for example), but when it first kicked off it sure was a thrilling program that totally worked. There were an amazing 86 of these Auto Trails that sprawled across America, including the Electric Highway that ran from Forsyth to Helena Montana, the Evergreen National Highway that connected British Columbia to Texas, the Geysers to Glaciers Highway bridging Glacier National Park to Yellowstone, the Mississippi River Scenic Highway, the National Park to Park Highway, the Yellowstone Trail, and of course the Arrowhead Trail, which became the very first scenic highway in Utah and Nevada and ran from Salt Lake City through Nevada’s southernmost tip and down to it’s terminus Los Angeles.

Imagining the Arrowhead Trail: Nevada’s First Scenic Highway

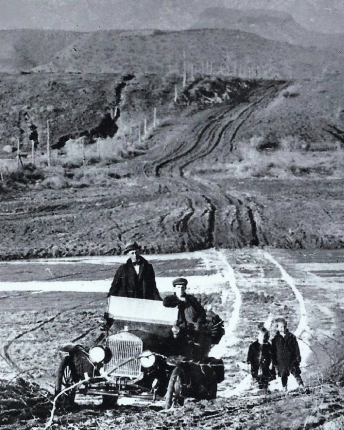

But, back to the very first, the Arrowhead Trail. While two other American Auto Trail highways predate the Arrowhead Trail I couldn’t find much info about them being scenic routes, but the Arrowhead Trail is exactly that, and was re-plotted and test driven for its off-roading capabilities about 10 years ahead of any others on the list. Originally a path used by the dinosaurs, then animals, and then humans, the Arrowhead Trail closely followed the Old Spanish Trail, which of course at its 1914 conception was in pretty rough shape. So the Auto Trail program developed a new route that closely followed this historic trail through Utah, Nevada, and California.

It’s a funny thing to imagine Utah searching for ways to drum up tourism, especially in a modern world where the West is absolutely overwhelmed by them with Utah’s Mighty Five as one of its main epicenters and ultimately where this exact route would drive right through. But that is one of the reasons the Arrowhead Trail was first dreamt up—to attract motorists who might want to see a world of geology unlike any place else. If you’ve ever been to the southwest, you’ll know what a mind-blowing experience it is to drive up and over the highest plateau in North America, cruise down into deep sandstone gorges, along the rim of the most famous canyon in the world, and in Nevada, through ancient sandstorms frozen in time. The Arrowhead Trail promised just that.

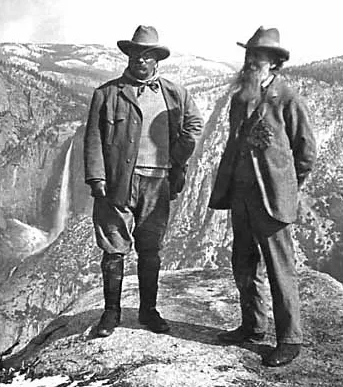

Charles H. Bigelow: The Face of the Arrowhead Trail

The only person crazy enough to set out on such a dangerous mission was Charles H. Bigelow, an American race car driver from Los Angeles, who was responsible for making the Arrowhead Trail look cool in its early days but also to prove it was viable for regular people to navigate. He was the exact right man for the job in a lot of ways, with experience racing cars in the very first Indy 500 in 1911 at the brickyard, the 1908 Los Angeles to Phoenix overland race, and he successfully navigated a 30 day race from New York to Los Angeles which included crossing the Santa Fe Trail—a route that no car had ever driven until Bigelow practically cruised right through it.

Bigelow became absolutely enamored with the American Southwest, determined to drive it all and while setting land speed records across many impassable landscapes from primitive automobiles. So one of the most famous racecar drivers in America and one of the few people actually qualified for the task, Bigelow successfully steered down the Arrowhead Trail from 1915 to 1916 in his trusted twin-six Packard he named “Cactus Kate.”

Again, knowing Utah is completely panicked with crowds today, back in 1916 the state of Utah only had around 35 miles of paved roads in the entire state. So once Bigelow basically re-mapped the route, he solicited the help of many Utah residents with “Good Roads Day”, where more than 400 locals brought their own teams of horses, plows, and scrapers to build the Arrowhead highway themselves.

Cruising into Nevada, and the Valley of Fire

A few segments of the route were constructed roads, though mechanical breakdowns, flat tires, and overheated engines in remote areas challenged even the most intrepid travelers, especially in those first few years the Arrowhead Trail was “open”. While plenty of regular civilians and later even St. George-area prison work crews rebuilt the route, Nevada’s section of the Arrowhead Trail was constructed, for the most part, at the hands of the Civilian Conservation Corps. Coming into Nevada from the Zion National Park region, the Arrowhead Trail dropped down into the Moapa Valley, through parts of modern day Gold Butte National Monument, through what would become Las Vegas Boulevard, down to Nelson and up and over El Dorado Pass, and into Searchlight.

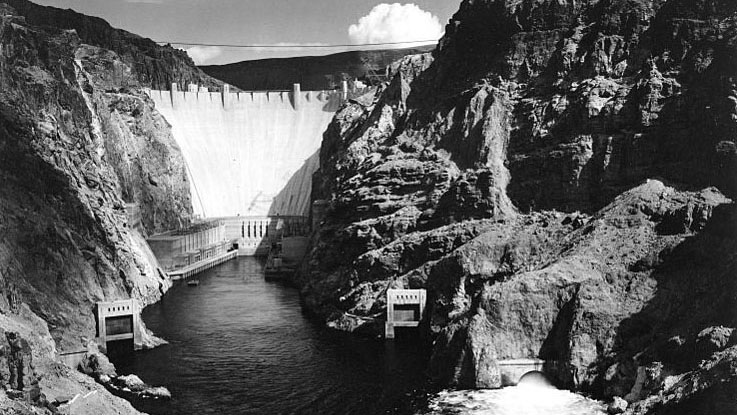

Even though this was at least 30 years before anything close to the Las Vegas Strip we know today became real, the powers behind the Hoover Dam project knew it would draw tourists to the southern Nevada region. And realizing just how successful this construction project was, President Hoover’s return-Americans-to-work initiative largely inspired the nation’s Civilian Conservation Corps program, but also shifted eyes to other tourism possibilities in the same vicinity of the Dam. So on the heels of its completion, in 1931 Nevada’s first state park was proposed, not far from Hoover Dam and also directly along the Arrowhead Trail.

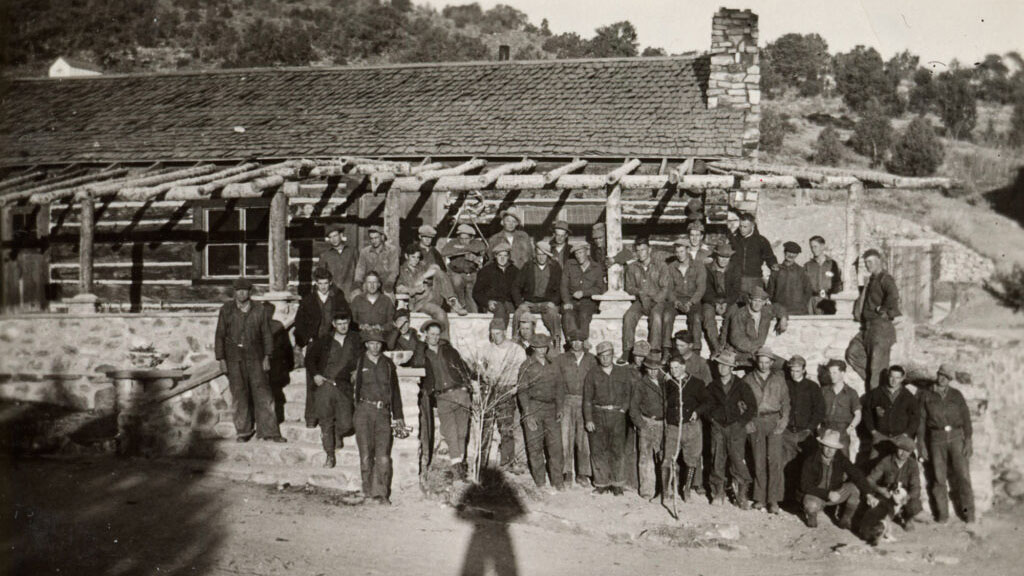

While Valley of Fire State Park is Nevada’s first, oldest, and now the most chaotically busiest, it was a white knuckle excursion to get in there during the nineteen-teens. Matter of fact, a AAA official traveling through during the 1920s described this red sandstone enveloped stretch of road as the Valley of Fire, noting when the setting sun touched it, the entire valley looked like it was set ablaze. While Nevada’s stretch of Arrowhead Trail was particularly rough and was initially built without a local population showing up with teams of horses and other road building materials, its brutal state didn’t remain that way for long. The Civilian Conservation Corps were officially assigned to build these lands into Nevada’s first state park in 1934, where they would go on to build a real road through the park—one of the most scenic in Nevada to this day, by the way, at least when it comes to paved roads, ironically so.

Along with that damn beautiful road that ribbons through some of the park’s most famous features, like White Domes Trail, the Fire (Bacon) Wave, and Mouse’s Tank, the CCC also built restrooms, firepits, and shade ramadas, all with a signature stone masonry you’ll learn to spot in Nevada state parks if you stick around long enough. But maybe what’s most special and unlike anywhere else, the CCC was assigned a special task at the Valley of Fire. Given how dangerous this particular stretch of the Arrowhead Trail was and long before any signs of a town existed within 75 miles (or more), it was decided folks navigating this region and visiting the park needed a place to stay—an overnight cabin, just in case they needed it.

And man, seeing sites like this—those few in Nevada the CCC were responsible building way back when—make me feel like I was born in the wrong era, or maybe even seeing my entire life as if I’ve somehow already lived it. Tourists have pissed me all the way off the few times I’ve visited Valley of Fire, mostly because they’re racing the hour away from the Strip in their rented sports cars just so they can either drive the theirs-for-a-few-hours Ferrari as fast as they can through Valley of Fire’s postcard-perfect roads, take pictures of their borrowed Lamborghinis next to vibrant Aztec Sandstone formations, or both. It’s transactional, and not the Nevada I’m talking about on this website.

But whenever I cross over that invisible threshold and into state parks boundaries or anywhere else I know CCC histories exist, I make sure to go straight to them. All the times I’ve stopped by the CCC Cabins in Valley of Fire, I’ve seen people drive down the quarter mile road leading to them and usually not even get out of the car to see what’s actually going on here. Either that, or they stand at the opposite end of the trail leading to the three cabins, shrug in some sort of disappointment, and hit the road in search of their state parks passport stamp instead of actually experiencing the park or this wonderful legacy.

Valley of fire ccc cabins, built specially for arrowhead trail travelers

Made from local sandstone, each of the three Valley of Fire CCC Cabins are modest ten-by-ten rooms and even come equipped with a perfectly masoned fireplace—how on brand is that. While anyone can stop by and even go inside all three of the rooms, the cabins are only open for day use now, along with every other feature within Valley of Fire park boundaries except the impossible-to-actually-reserve campgrounds. Minutes away, you’ll also find the CCC’s work in Overton, which is one of the gateway communities to the Valley of Fire, where they performed their first (and one of their only) archaeological digs, resurrecting the Ancestral Puebloans’ Lost City, and helped build the museum to house all the artifacts recovered, too. Further up the road, the CCC also did tons of work at the now-designated Gold Butte National Monument, where they built roads and a dam.

I think one of the reasons I’m so enamored by the work of the CCC is because these teams of men were responsible for building most of my favorite places, and with so many people unfamiliar with their efforts, knowing that info makes it feel like a secret, or something. Something worth another look, and places worth protecting whether they’ve been made into state or national parks by now, or not. Like when you know how to spot their work, the legacies of these men are suddenly right there in the truck with you. I think that’s why I’m also so fascinated by the Arrowhead Trail, because while portions of this road did turn into modern stretches of interstate in Nevada and beyond, most people have no freakin’ idea. And even when they’re led right to it, like at Valley of Fire’s CCC Cabins, they still don’t get it.

But there, tucked away in the Nevada desert, lies a modern day state park that was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps, only because the road had been forged by one of America’s most badass off-road race car drivers, only because the path had already been relied upon as a historic trade route, only because it was followed by the first humans for thousands of years before that. Here lies a stone masoned cabin that sits in front of ancient petroglyphs, but is only available to those who really choose to see all that’s actually here.

So whether it’s hugging every whoop in Monitor Valley, following every bend and hug of the Walker River, every last mile of rattle-the-truck-loose in Gold Butte along the lost Arrowhead Trail, or whatever else may be your fave great drive in Nevada, think of someone like Bigelow’s tail lights leading you over the next bluff, and the thousands of people who’ve followed that route before him, and in all the years since. I know I sure will.

Sources

- “Arrowhead (Trails) Highway”, U.S Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management, December 2023, https://www.blm.gov/visit/arrowhead-trails-highway

- “Arrowhead Trail – Henderson”, Nevada State Historic Preservation Office, December 2023, https://shpo.nv.gov/nevadas-historical-markers/historical-markers/arrowhead-trail-henderson

- “Auto Trail”, Wikipedia, December 16, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Auto_trail

- Church, Lisa Michele, “Red Rocks and Race Cars: Charles H. Bigelow and Tourism Development Along the Arrowhead Highway”, November 18, 2018, https://wchsutah.org/people/charles-h-bigelow7.pdf

- Cronon, William. 1995. The Trouble With Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature. New York, NY. W.W. Norton & Co.

- “History of Valley of Fire State Park”, Nevada State Parks, Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, December 2023, https://parks.nv.gov/learn/park-histories/valley-of-fire-history

- “Michelin Man”, Wikipedia, October 18, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michelin_Man