Prefer to Hear this story Instead? Listen Here.

There are few things I love more than my cow dog I busted out of a cow town. He’s never not with me.

But, I think most of us who have dogs in our lives feel that way—that sort of can’t-go-anywhere- without-them kind of big love that only builds on itself the longer we have them around. And while this unmatched canine camaraderie has basically been revered as the original, model companionship since the beginning of time, they weren’t always treated as the loyalists we know of them today but were more of a tool used to track, hunt, haul supplies, guard camps, and even babysit. And funny enough, contrary to mainstream belief, not all of them came with us from Europe—not even close.

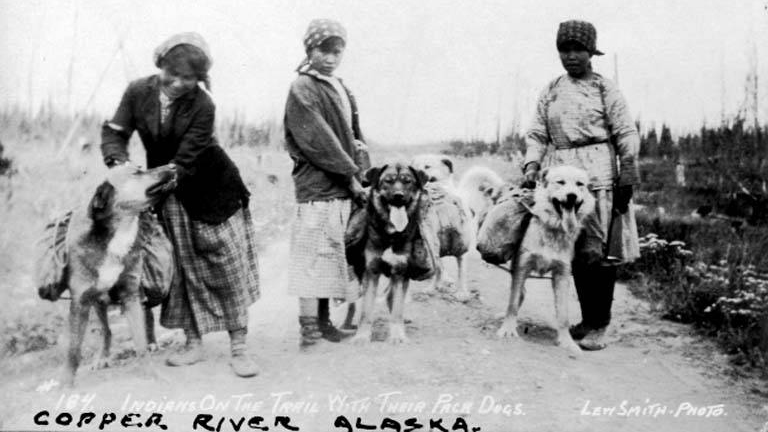

When 19th century explorers and naturalists first set foot in America and the West, they not only encountered this country’s original population of people but also their dogs, and were oftentimes shocked (translation: scared) by their wild, wolflike appearances, differing from a lot of the schnauzer and terrier-type dogs they knew, and may have left back home. The dogs before them were large, strong, and didn’t bark but howled. And like the American Bison, Coyote, and the rest of North America’s unfamiliar, endemic brood, the American Indian Dogs were instantly feared by Euro-explorers, becoming part of their list of things that needed conquering (and eradicating) in this terra incognita.

Even though a lot of people choose to believe America’s first dogs were brought over by Europeans, the truth is they weren’t. America’s first dogs—which are sometimes called American Indian Dogs or Plains Dogs—were living in North America for thousands of years before those first explorers ever even arrived. While millions of dogs are found in homes all across this country nowadays, the original American Indian Dogs are nowhere to be found, their genetic legacies obliterated from the genomes of all living dogs today.

But back before the Plains Dogs were completely wiped from our history and became a Legend of Lost Nevada and far beyond, they slowly but surely became man’s best friend alongside this country’s first people.

And with DNA recovered from these ancient beauties revealing where America’s first dogs came from and how and why they disappeared, it’s the story of original friendship, and that of Danger Cave: one of the oldest canine burial sites ever recorded in the Great Basin, and the world.

The American Indian Dog’s Arrival to the Americas

It’s amazing how DNA science has really changed the way we think about everything. At least within the last 60 years or so, it’s shifted our reality of what we “know” about our most devout friends: our dogs. Things really started to turn a corner when archaeologists discovered ancient canine remains curled up in individual grave-like pits in Illinois during the 1960s and 70s. Remarkably, the remains at these two sites—called Stilwell II and Koster—were radiocarbon dated at an astonishing ten thousand years old, not only making them the oldest known dogs in the Americas at that time, but also the oldest solo dog burials anywhere in the entire world.

That revelation redrew the timeline entirely. Even though the story we Americans “remembered” is that we brought dogs with us across the Atlantic, having these ancient dog burial sites pop up all over North America disproved that narrative, and fast. Additionally, these ancient tombs weren’t just unveiling the discovery of canine skeletal remains, but illuminated the fact that someone took to the sentiment of laying a dog to rest in its own grave. So, the dog didn’t simply just stay in the spot it ultimately perished, but was buried with ceremonious intention in his own final resting place. Two pretty remarkable revelations in one.

Once the Illinois sites were rediscovered and blew the freakin’ minds of archaeologists in all corners of the continent, it became theorized that the first dogs may have come to the Americas from Siberia a few thousand years after the first people showed up. We know that humans entered this part of the world around 16,000 years ago using the Bering Land Bridge, which connected Siberia to Alaska. Then five thousand years later, glacial meltwater submerged the Bering Land Bridge forever, but it’s believed America’s first dogs must’ve naturally come from a place north of Siberia called Zhokhov Island, and followed people across this natural bridge before it vanished for good.

So what would become known as American Indian Dogs cruised over from Siberia to Alaska, and then archaeologists estimate the dogs probably stayed there in the Alaska region for a while alongside people, not venturing deeper into the Yukon Territory and the belly of North America until later. After the Illinois revelation, several more ancient dog burial sites were recovered in Alaska, Wyoming, near a place called Jaguar Cave in Idaho, and throughout the Great Basin.

Mostly all of Nevada’s prehistoric dog remains were discovered near ancient lakes or what would’ve been wetland habitats, like Lake Winnemucca (one of the oldest human-populated places documented in North America, by the way), Stillwater Marsh, and Desiccation Cave near Pyramid Lake, though none seemed to have been entombed in a grave, or buried with intention. That, and while dogs first appeared in the Great Basin 10,000 years ago, in a region whose human population has always been very low, there’s not been much significant evidence of them here compared to other places. At least, not until Danger Cave.

Meet the American Indian Dog: The First Generation of Our Best Friends

Compared to the DNA of 145 modern and ancient dogs, the American Indian Dogs have a special genetic signature not found in any other canines on Earth. In other words, these “precontact dogs”, as scientists sometimes call them, have a genetic makeup unlike any other dogs we know today, completely distinct from all modern breeds not just because other European breeds would eventually outnumber them, but also because colonists brought disease, violence, and a way of life that devastated tribal populations and everything that belonged to them, including their dogs.

Some modern dog breeds share similar genes—like the Siberian Husky, Alaskan Malamute, or even the Mexican Xoloitzcuintli— though the purebred, ancient Plains Dogs died many generations ago. The pros estimate that there were three types of aboriginal domesticated dogs in North America, though most of these ancient breeds fall into two categories—large, and small— with the larger being most similar in size to coyotes, and the smaller more consistent with foxes.

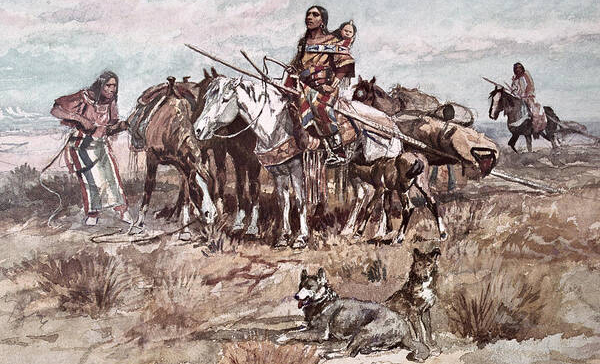

The first people to domesticate these wild dogs were the Plains Indians, who lived mostly in the (modern day) central part of America—so from Montana and Wisconsin, down through Texas. It wouldn’t take long for the Plains Indians—whose population was made up of thousands of people from dozens of tribes ranging from the Blackfeet, to the Crow, Osage, Comanche, Arapaho, Apache, and beyond—to become known as the “dog breeders” to other tribal nations not just because of their sheer population of the 300,000 dogs they kept with them, but also because they bred, and traded dogs with nations all around them, ultimately making this amazing Plains Dog super-breed to do exactly what they needed.

From the northeastern areas, they mixed quiet hunting and herding types with the barking, bear-hunters of the northwest, and larger village Indian dogs from the north with smaller pueblo dogs from the southwest that ultimately made a dog with all the best, most desirable qualities that didn’t have anything to do with companionship—at least, not yet. These medium-sized super-dogs could pretty much do any and everything these many tribal nations could imagine, ranging from pulling sleds and toboggans responsible for transporting food and supplies, to tracking and corralling buffalo and hunting big and small game, and eventually were trusted to guard camps, babysit small children, and keep their masters warm on frigid nights.

The American Plains Dogs were medium-sized good boys and girls, with short to medium coats of pretty much all natural hues with longer, fluffier hair around their necks, called a rough. With masked faces, pointy ears, and light yellow, gray or blue eyes, these dogs weren’t only excellent tools for the many tribal nations across the country, but were striking creatures, too. So handsome in fact, that entire groups of modern dog breeders have tried their damndest to resurrect these ancient beauties. But like the original genetic makeup of the American Bison—another creature whose eradication was made by design—are now only a legend.

Plains Dogs in the Great Basin

With the Plains Indians the savviest dog breeders and traders this country has ever and probably will ever see, the majority of these legendary dog populations were with them in America’s center. Nevada’s ultra-rurals are among some of the least populated terrain in America nowadays, which has basically always been the case—populations were obviously even lower around here back then, and few people meant even fewer dogs. While we know American Indian Dogs did belong to and lived with the Northern Paiute from the Walker River to the Pyramid Lake regions, a slightly higher number of American Indian Dogs were said to have lived with the Shoshone in the northern regions of modern-day Nevada, too.

As I mentioned earlier on, most of the ancient canine excavations in Nevada’s Great Basin were few, and recovered around places that still do, or used to have lots of water. If these aboriginal dogs weren’t with groups of people (which was relatively unlikely in Nevada), it was easiest for them to survive in a wetland habitat where they could rely on water, and other game drawn to it. And while the flowing, Truckee River waters were dammed and diverted from Lake Winnemucca now more than 120 years ago and Lake Bonneville as one of the most famously dry playa surfaces on Planet Earth, they weren’t always that way, but instead ideal wetland habitats for people and domesticated dogs to live alongside.

Rediscovering Danger Cave

There, on the edge of the ancient Salt Lake glacial sea less than a mile over Nevada’s eastern border in the Great Basin Desert, is Danger Cave. Like many other caves perched high above what would’ve been basins filled with massive lakes, America’s first people used these rock shelters for many reasons, ranging from reliably dry places to store things that included things like traded goods, hunting tools, and even sacred burial sites, to a natural refuge that would protect them from the high desert’s harsh elements. At least this has been the case with Nevada’s Lovelock Cave, Hidden Cave, and Toquima Cave. Danger Cave was no different.

The thing that really blows my mind about these Great Basin caves is that new arrivalists to the West didn’t really pay any attention to these sites until the 1920s or after, and even then, only because they realized they could mine guano (bat poo) for fertilizer, which naturally occurred in most Nevada caves. And even then, these sacred sites—some containing the oldest artifacts of their kind in the entire world—only caught the attention of historians and archaeologists when guano miners made statements like “there are so many Indian artifacts here I can’t do my job, they’re in the way.” Only then did people say, “Hey wait a minute, something valuable might be here.” That will never not blow my mind.

But it’s basically the same rediscovery story of West Wendover’s Danger Cave, where archaeologists wouldn’t officially study it until 1941 when archaeologist Jesse Jennings and his crew started to notice what may actually await here. Wendover experienced its most significant population boom right around this same time because the US Military made this remote corner of Nevada desert a WWII Air Force Base that would house the Enola Gay—or the first aircraft to drop an atomic bomb in warfare, the one that dropped the A-bomb on Hiroshima.

Military men and their wives knew about this cluster of caves perched on the edge of town overlooking the Bonneville Salt Flats mostly because they made the ideal place to throw elaborate parties during national blackouts. Matter of fact, one right next to Danger Cave became Jukebox Cave because the young Americans stationed here actually dragged a jukebox into the cave, poured a concrete dance floor inside of it, and basically made the ideal hidden party spot naturally sheltering any light or signs of people during these nationally-mandated blackouts during wartime. What a trip to imagine that, right?

But, they didn’t use Danger Cave for any parties, mostly because the surface area leading up to the cave was so steep it was originally named by locals as “Hands and Knees Cave” because the only way you could actually reach the entrance was exactly that: by crawling up there on your hands and knees. But, its steepness didn’t keep Jennings and his team of archaeologists out, who began excavating the cave in 1941. And, they’re the team responsible for giving the cave its current name, Danger Cave, after a bunch of enormous boulders fell from a rocky ledge overhanging the cave, nearly crushing them. You can still see the rocks that fell.

Here, Jennings and his team would realize the 100-foot-deep by 15-feet-tall Danger Cave was an extremely dry place that made ideal storage conditions for the Ute, Paiute, Goshute, and Shoshone Nations who first lived here. Inside Danger Cave, Jennings and his team were able to uncover textiles and tools, more than 2,500 chipped-stone artifacts and over 1,000 grinding stones, animal bones, and beetle wings and remnants of 68 plant species, which were important because it changed the way we thought about time and people in this part of the world that spanned a history of more than 10,000 years, framing up a new view of otherwise little-known Great Basin Desert culture.

During this study, Danger Cave’s first archaeologists were able to discover that the rock shelter supported a tiny population of people somewhere around 25 to 30. He and his team were able to realize that their focus on survival prevented them from building permanent structures, developing complex rituals, or even amassing lots of personal property. But it wasn’t until 1980 when a second team of archaeologists realized the bones recovered here was the earliest evidence of domesticated dogs ever discovered in the Great Basin, and all of North America.

Realizing One of the Oldest Canine Bones Ever Found

While Jesse Jennings’ work recording Danger Cave’s ancient history filled in major gaps of what we know about the human histories of the Great Basin Desert, they originally believed the animal bones recovered from a grave-like pit inside the cave belonged to a bear. But then in the 80s, a study with an emphasis on dog evolution revealed the remains found in the Danger Cave tomb were that of the oldest domesticated dog remains in North America—even older than those sites originally recovered at Stillwell II and Koster in Illinois.

Believed to be somewhere right around the 9,400 year mark, the Danger Cave dog remains (buried with absolute intention in a grave inside the cave), were the oldest in the Americas all the way up until 2021, when an even older specimen was discovered in southeast Alaska. So there, on the edge of an ancient prehistoric lake that spanned 20,000 square miles, inside an ancient cave occupied by the first people to ever live in the Great Basin, some of America’s oldest canine remains were discovered. Yet, I’d be willing to bet it all inside those Wendover Casinos that most people never even take their eyes off that giant, 60-foot-tall neon cowboy waving you off the interstate and into another bizarre Nevada border town. If only people could stop seeing the version of Nevada they’ve decided it must be—empty, dead, and boring—and realize what awaits in every mountain range and high desert valley before you, Nevada would embody a completely different set of adjectives altogether.

In a culture that’s not only obsessed with figuring out the exact genetics we have but also that of our dogs, I can’t help but wonder if those Plains Indians-bred super-dog genetics did influence the modern dog—seems pretty ignorant to believe otherwise. Could Elko, my cow dog mutt that I adopted from an Elko, NV animal shelter have some ancient breed in him? While those DNA strains disappeared long ago, he sure ticks the boxes of almost all of the Plains Dogs characteristics and it’s fun for me to wonder about as I see his head poke through the back window, with the Great Basin framed up behind him, as we bump down Nevada’s most remote gravel roads.

When I started my Song Dog Silver Nevada turquoise business in 2022, I went to look and see what other enterprises may exist with the words “Song Dog” in them. The only other listing that turned up was something called Song Dog Kennels—a place I originally thought to be some kind of a dog boarding business, but never really looked into it much, knowing they weren’t a jewelry business.

Now a couple years later, after learning the histories of the American Indian Dog and the Great Basin’s place in it, I went to research more information about this fascinating legacy only to realize Song Dog Kennels isn’t a dog boarding place at all, but the original copyrighted registry of an American Indian Dog breeder. Founded in 1965, this group leads most of the modern-day research we depend upon for information about this fascinating lost breed with a mission to “maintain the true descendants of the “old dogs”.

With a coincidence that rich, I know I didn’t find this Legend of Lost Nevada, it found me.

Sources

- Cerny, Brittany, “Native American Indian Dog: Origin, Fun Facts, and How to Adopt One”, Pow Wows Inc., January 8, 2024, https://www.powwows.com/native-american-indian-dog-origin-fun-facts-and-how-to-adopt-one/

- Clark, Elaine, “Danger Cave still evokes life as it was at Great Salt Lake of 8,000 years ago”, KUER 90.1, December 27, 2022, https://www.kuer.org/health-science-environment/2022-12-27/danger-cave-still-evokes-life-as-it-was-at-a-great-salt-lake-of-8-000-years-ago

- “Danger Cave”, Wikipedia, January 7, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Danger_Cave

- “Danger Cave State Monument and Juke Box Cave Tours, Metcalf Archaeological Consultants, March 2024, https://metcalfarchaeology.com/danger-cave/

- Grimm, David, “America’s first dogs lived with people for thousands of years. Then they vanished.”, July 5, 2018, https://www.science.org/content/article/america-s-first-dogs-lived-people-thousands-years-then-they-vanished

- “Jolley, Faith Heaton, “The story behind Utah’s Danger Cave”, KSL Broadcasting, April 29, 2015, https://www.ksl.com/article/34442210/the-story-behind-utahs-danger-cave

- Lupo, Karen D., and Joel C. Janetski, “Evidence of the Domesticated Dogs and Some Related Canids in the Eastern Great Basin”, UC Merced, July 1, 1994, https://escholarship.org/content/qt1h1946p4/qt1h1946p4.pdf?t=krnljr

- “No, it wasn’t a bear: Scientists discover oldest dog in North America”, Nexstar Media Group, Inc./ABC4 Salt Lake City, February 24, 2021, https://www.abc4.com/news/no-it-wasnt-a-bear-scientists-discover-the-oldest-dog-in-north-america/

- “Plains Indian Dogs”, SixKiller Designs and LaFlamme Farms, March 2024, http://www.indiandogs.com/plains.htm

- “What’s so special about Danger Cave?”, Utah Humanities, July 1, 2011, https://www.utahhumanities.org/stories/items/show/221