Prefer to hear to this Story Instead? Listen Here.

The desire to be truly free, and answer to no one. How far would you go to protect it?

It’s a word and philosophy that sure gets flung around a lot, freedom, and maintains its powerful luster because it’s a subjective thing. It means something different to everyone. For me, I’ve found I tend to feel the most protective of the days where I’m out in the middle of nowhere Nevada, completely self-sustained in an off-the-grid camp setup with my husband and dog. It’s just us and the Great Basin Desert, where barrenness, aloneness, enormity, and unforgiving beauty is the attraction. Either that, or I safeguard the feeling of coming across a place that most people dismiss for its “nothingness”, but knowing we’ve seen enough Nevada to realize that whether it’s a lump of turquoise, an old pioneer cemetery, or a hot creek, there’s something else there that’s earned a second look.

That rural Nevada contact high is something we’ve become completely addicted to and protective of through the years, but at the end of it, we always come back. We come back home to our ordinary house in an ordinary neighborhood. Sleep in an ordinary king-sized bed, take an ordinary shower, eat ordinary meals, and return to ordinary jobs. But what if we didn’t? What if we just stayed out there in the magic? And just how far would we actually go to protect our opportunity to keep experiencing it? If you’re Claude Dallas, well, I guess that means using both barrels.

With this series of stories, it’s obvious I am fascinated by Nevada defenders, and the place (and those feelings that come with it) they so boldly protect. Most of the time their life story is an admirable one, and the bridge to more intimately understanding some of the most isolated places in America. Then there’s Claude Dallas who, for better or worse, is definitely the most polarizing Nevada folk hero I’ve personally learned the story of. Where he chose northern Nevada’s mighty peaks and colossal valleys because he could do whatever he wanted, answer to no one, and remain undetected.

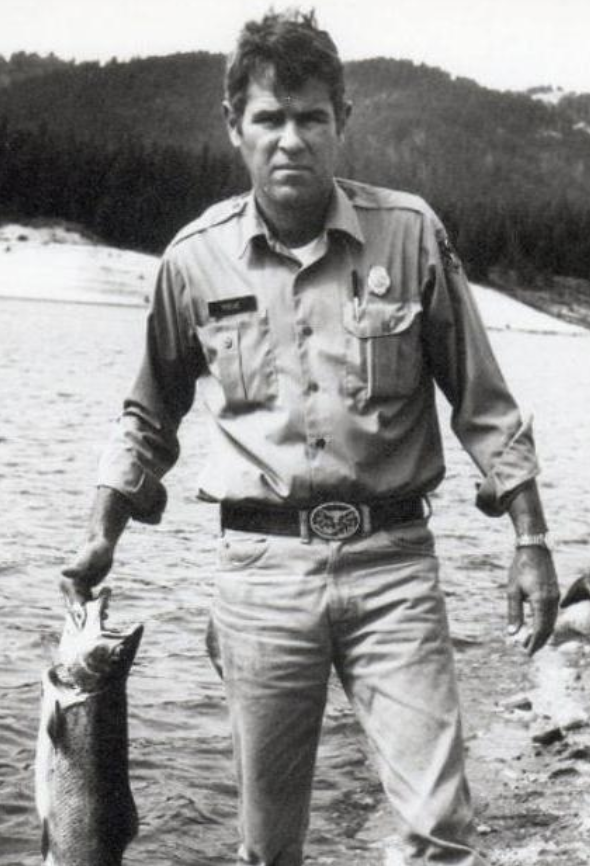

Maybe the craziest part in all of it is this: he’s a person who is still alive and still seeking refuge in the high desert, and some who’ll say served his time while others will argue a life sentence would never be enough. It’s not only an almost-unbelievable true story, but one that happened recently. And one where a whole lot of northern Nevadans not only know of his story, but have very divided, very strong feelings about this new outlaw living in an old west. A lot of his acquaintances and neighbors would defend Dallas’ character as truthful, a hard worker, a man’s man, the best cowboy around, a person who loved fresh air and animals, an amazing listener, individualist, and a direct gentleman. His victims would describe him as an antisocial loner, a gun nut, underdog exile, a survivalist, a renegade who can’t live among people, sociopathic manipulator, and later, a remorseless killer who committed the unthinkable act of killing two law enforcement officers.

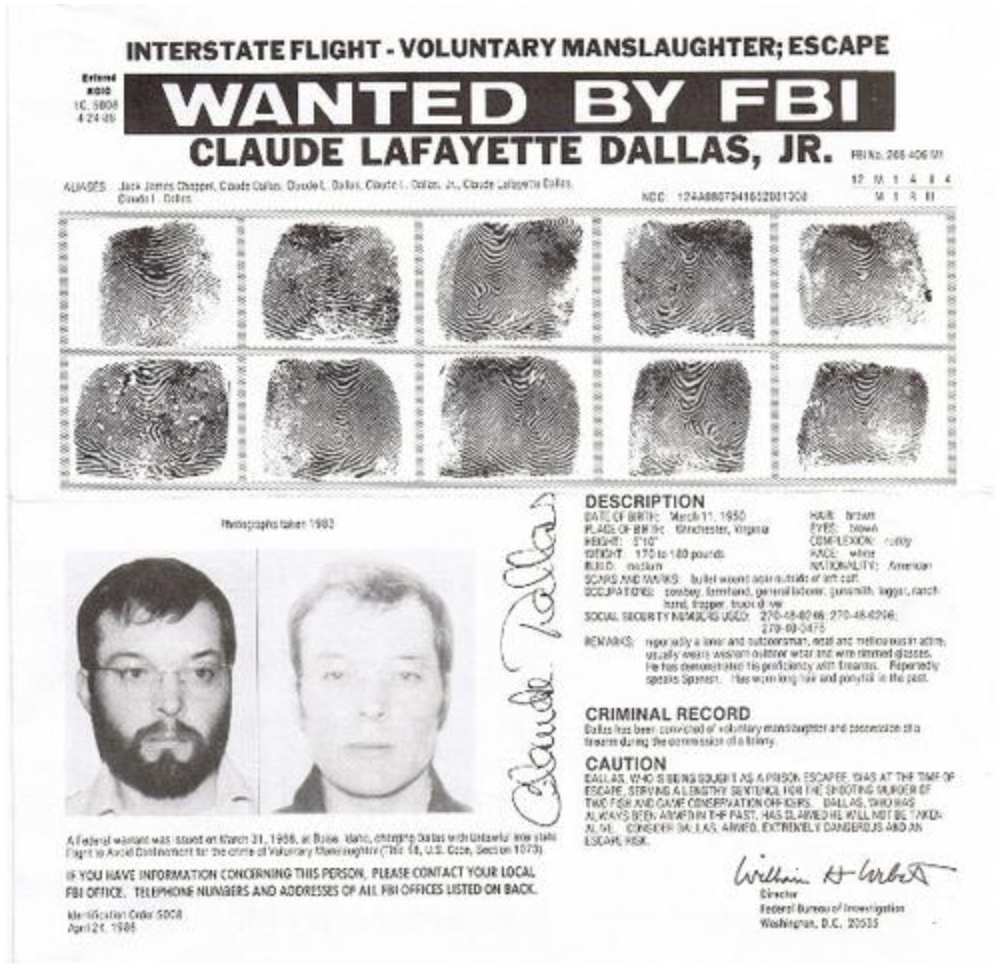

Roaming the Owyhee and Paradise Valley in the ruggedly remote mountains of north central Nevada, Dallas was the type of guy who could be on the minds and mouths of everyone, but was nowhere to be found and in the end, was perhaps only caught because he wanted to be. A lot of Westerners believe if you give a boy a gun you’re making a man. But in Dallas’ case, where did dozens of guns, thousands of rounds of ammunition, countless illegal traps, pelts and hundreds of pounds of poached meat, and pure disdain and defiance for the law actually get him? One of the more elaborate manhunts in United States History, being on the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted List, and the subject of the longest and one of the most confusing court cases in Idaho history—that’s what.

This one is a long, complicated, and sensitive true story that still divides many Nevadans. So, pour yourself a Picon, and decide where on this sensational spectrum you land. It’s the Legend of Claude Dallas: the most infamous nomadic poacher and remorseless mountain man Nevada’s ever seen.

A Boy From Winchester Who Wanted to Be A Cowboy

Claude Dallas grew up pretty damn unremarkably. Part of a regular, middle-class family from Winchester, Virginia, the Dallas family relocated to Ohio when he was a young boy. There, they purchased, and made an ordinary life for themselves on a dairy farm. Dallas apparently hated it. During his adolescence he became enamored with books about the Old West, where he dreamt about rustling cattle instead of milking them. According to his folks, the next thing they knew, he wanted to be a cowboy. And that’s pretty much exactly as it went.

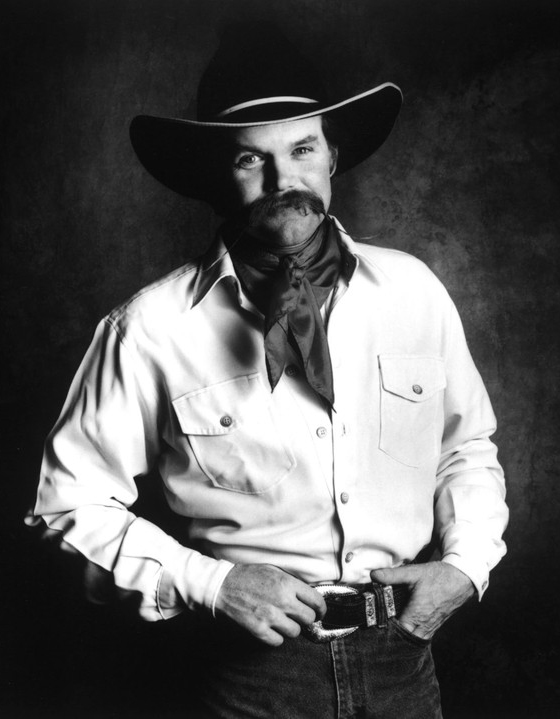

As soon as Dallas turned 18 and graduated from high school, he hit the road, hitchhiking West in pursuit of becoming a real life version of the characters from the pages of his books. This was during the late 1960s by the way, when the Vietnam War was reaching its peak violence and enforced its draft lottery system. Of all places, he landed in an isolated stretch of southeastern Oregon at the Alvord Ranch, which is basically just north of McDermitt, Nevada. Almost instantly, he was hired on as a ranch hand where he would actually become a real cowboy, or in this part of the West, a buckaroo. And by the sound of it, he really played the hell out of being one.

It seems like no matter the subject, if you ever ask the generation before you about the way it was, they’ll tell you it was purer, less complicated and basically just better. Back when you didn’t need a camping reservation, there were no speed limits, no light pollution choked out the stars, geothermal power plants hadn’t tapped natural hot springs yet, and cattle operations were still enormous and super successful—you get the idea. I’ve had the chance to talk with a lot of real buckaroos through the years, somehow most of whom also cowboyed during this same late 1960s to mid 1980s timeframe, and from what I could string together, it was during this time (when Dallas was cowboying in the same region) that a lot of really huge and really famous cow-calf operations were still running full throttle. The glory days of being a real buckaroo on ranches that were hundreds of thousands of acres, with hundreds of thousands of cattle they were responsible for.

Dallas was doing real cowboy shit up there on the Alvord Ranch, oftentimes doing the jobs nobody else wanted to do, inching closer to the old definition of a cowboy, or despising any work that took him off his horse. He sure sounded like a tough dude, and heartachingly and uncharacteristic to most cowboys, almost immediately showed violence toward animals. Back then Dallas was the type of guy who didn’t see anything wrong with shooting any animal, at any time, for any reason. Within the first few months of living and working on the Alvord Ranch, he was said to have badly kicked dogs, constantly baited illegal traps out of season, and insisted the laws didn’t apply to subsistence hunters. With his first few paychecks, Dallas immediately bought a gun, but not just any gun: a Winchester Model 94 Rifle, or “the gun that won the West.” He was a legitimate authentic buckaroo, but was also said to be pretty flashy about it, where locals joked he dressed as if he stepped out of the pages of the Buffalo Bill show catalog.

Dallas lived and worked on the Alvord Ranch for a few years before heading south into Nevada, into a place called Paradise Valley. Situated about 50 miles from the Idaho-Nevada state line, Paradise Valley has always been a region of people known for forging their own way. It’s a remote north central stretch of Nevada that’s long been home to Basques, real buckaroos, hunters, and a lot of conservative, self-reliant people who don’t usually ask for help or permission. Paradise Valley, NV is about an hour north of Winnemucca, and when Claude Dallas arrived in the early 1970s, Winnemucca only had about 4,000 residents (compared to its 8,300 today.) On the way into the valley from Winnemucca, there’s a junction right off the highway called Paradise Hill, and is where the majority of this story all happened.

It’s also an absolutely gorgeous place, encircled by several rugged mountain ranges like the Bloody Runs, Krum Hills, the Osgoods, and the Santa Rosas. In the driest state in America, you can imagine how uncharacteristically verdant this place is, considering it’s at the foot of many high elevation mountain ranges that all drain into one 40 by 12 mile long valley. Here, Dallas got a job as a ranch hand on a Paradise Valley operation, though he didn’t really behave like most of the other buckaroos in the Valley.

It was said that Dallas was never too interested in the ladies, and was basically your classic desert recluse from the jump. He loved to talk about guns, and was more interested in sharpening spurs, custom fitting pistol grips to his own hands, or melting down lead to forge his own bullets. And let me put it to you this way: people noticed. From what I read and researched about him, it sounded like people kinda felt sorry for this new, sorta introverted loner, and adopted him as theirs. One guy in particular especially so: George Neilsen, who owned the local bar and basically became a pseudo father figure to Dallas.

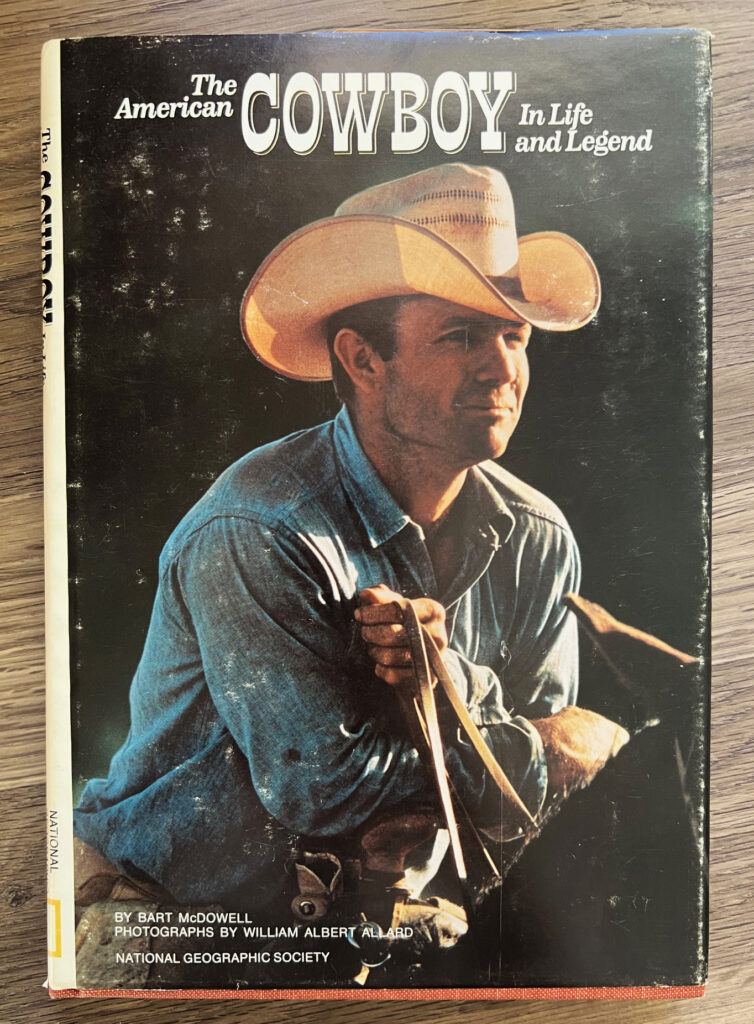

The American Cowboy in Life and Legend

As Dallas’ confidence for his work increased, so did his pure defiant hatred for authority and the law, especially when it came to any sort of hunting regulations. I read that local fishermen routinely crossed the boundary line of the property he cowboyed at, and in response, he put up 7” spikes to blow out their tires and send a serious message. A pattern for severe behavior was starting to emerge here.

So meanwhile back in Ohio, Dallas started receiving draft notices, ordering him to report for induction into the US Military for the Vietnam War. But whether this was a legitimate or deliberately turned blind eye, a warrant was issued for his arrest for failing to show up. The craziest thing? He ultimately got caught because he was photographed and featured in a cowboy book put together by National Geographic, published in 1972. To say I was completely fascinated by this is the understatement of all understatements, so I immediately tracked down a copy of this book to have a look for myself.

Titled The American Cowboy in Life and Legend, the pages of this book live up to my imagination, bringing to life the old ways of cowboying that I’ve heard described to me so many times by so many different cowboys, particularly each January at the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko. From the Great Plains, to the American Southwest, to Texas Hill Country, to Nevada’s Great Basin, the book is a really beautiful love letter to the American Cowboy. I recommend finding your own copy for only a few bucks.

So, I got this thing in the mail and immediately started scouring the pages, looking for photos of Dallas, and what would eventually get him caught and arrested for evading the Vietnam War Draft. And on page 133, there he was—sitting around a camp, drinking a beer with his cowboy comrades, with a caption that reads, “This camp, an old homestead called the Little Humboldt Ranch some 40 miles from the headquarters of the Nevada Garvey Ranch, shelters Quarter Circle A buckaroos heading for work in the spring pasture. There they live in tents, while watching after 25,000 head of cattle.”

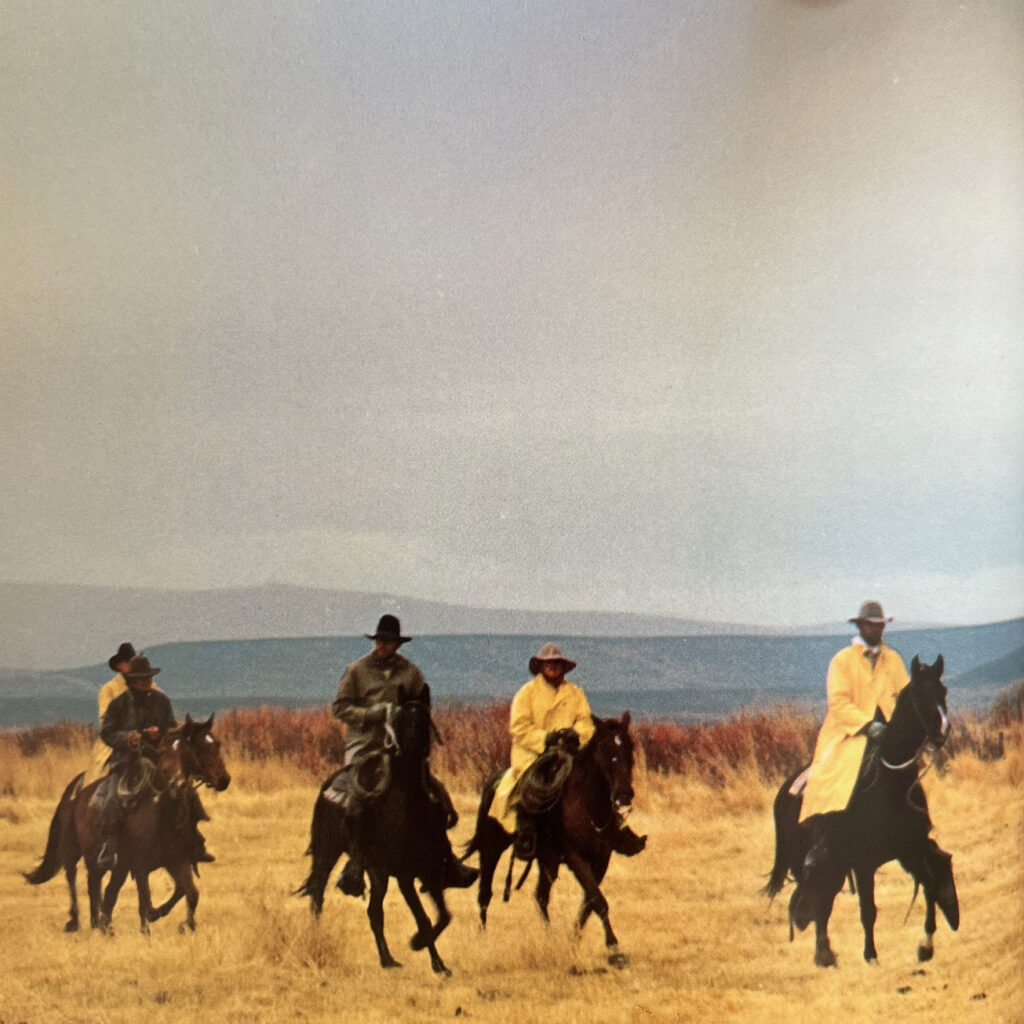

And on the next page, there he is again, galloping across the high desert in yellow rain ponchos with other buckaroos, and from what I can put together, is the photo that would ultimately get him caught.

He was charged with draft evasion and what would become his first official arrest, though he would eventually be pardoned. I read something about how his response was that he would fight for his country if he was asked nicely, but wouldn’t stand for being ordered around. From here, his contempt for the law and really being told what to do by anyone else was officially on the fast and steady climb.

Nevada Public Lands

The Owyhee is rugged countryside. With places with names like Defeat Butte, Skull Creek, Starvation Springs, Devils Corral, and Poison Creek, it really paints a picture of not just the landscape, but also the type of people who chose to live here and ultimately defend it. Its uncomplicated solitude appealed to Dallas—here, he could basically live however he wanted, completely undetected.

We know his favorite subject was guns, but he also loved to talk about public lands, especially when it came to rules and regulations. Like most rural Nevada recreationalists, myself included, public lands are not just important, but at the center of the Nevada experience. With a higher percentage of public lands acreage than any other state in America, your ability and right to wonder what’s over there down that valley then actually go find out is possible here, and not the case in most other places. It’s been this way since Nevada transitioned from a territory to an official state back in 1864, mostly because I think state officials wanted to foster the ability to bore into any mountain and valley possible in order to keep mineral bonanzas flowing. Yet, now more than 170 years later, the threat of privatizing public lands for personal gain is very real, and very annoying—at least to me.

Claude Dallas sounded like he wanted it both ways: he was a guy who went to public schools, spent most of his time on public lands, killed public animals, and drove on public roads. And while he was also protected by public armed forces, police, and firemen, he detested the law. Especially game wardens—or the people responsible for enforcing hunting, trapping, and game laws—in particular. To a lot of people choosing to live in the extreme rurals, they’re “emissaries of flower-fondling environmentalists.” To everyone else, they’re to be as respected just as much as any other badged law enforcement officer.

Transition To Mountain Man

So remember George Nielsen, the bar owner in Paradise Hill that took Dallas under his wing. And besides running the main watering hole in the area, Nevada Fish and Game had their eye on Nielsen because they kept hearing rumors about him selling poached venison and chukar to migrant workers on the side, under the table. They weren’t wrong. And while Dallas did the hell out of the cowboy thing from 1968 to 1975, by the mid 1970s he basically turned into a mountain man, trapping animals full time. Now he would reach even further back into history and the pages of his Old West books by becoming a real mountain man.

He began an under-the-table pelt scheme with George Nielsen, where Dallas would illegally bait traps, not follow any seasonal regulations, and killing far beyond allowable limits. He was living in open violation of game laws in every way possible. He didn’t just set out a few traps, but was said to cover entire mountainsides with illegal lures which not only took the sport out of it, but was fully illegal. Even the biggest outdoorsmen in the region knew it was obvious he was more interested in killing than trapping.

To make a bad situation even worse, Dallas began shooting wild mustangs for food to survive off of, but would also use it as bait for other animals he wanted the pelts of, like coyotes, mountain lions, and foxes. So the idea was, he’d shoot the horse, take some of the meat for himself, then wait for coyotes and bobcats to feed off of it and then gun them down for their pelts, which he gave to George Nielsen to deal from the back door of his Paradise Hill Bar. He bragged to an off-duty cop hanging out at the bar one night, and even went to lengths to show him hides that were missing toes and tags. So, the law was definitely onto the two men.

Even though this really remote region of north central Nevada was so enormous he could successfully run these illegal traps undetected for years, eventually he was cited for baiting traps, which of course was definitely illegal. He was ticketed for illegally baiting and trapping mountain lions. He only had to pay a small fee of course, and immediately bragged to Paradise Hill Bar patrons that he didn’t want to make any trouble for the landowner, otherwise he would’ve shot the game warden who cited him.

Tensions between Dallas and game wardens continued to mount, where Idaho game wardens knew Dallas was illegally baiting many, many traps, staked him out, and took his guns. We know he was pretty much gun obsessed, and the only way he could actually get them back was to go get them from the Conservation Officers and of course pay an additional (small) fee. Basically with his tail between his legs, he retrieved his guns and of course paid his fines, but also bragged that he “wouldn’t get caught again”, and also made comments about how fun it would be to be on the lam.

While his artillery collection swelled and his tastes for extreme isolation intensified, people living in the area basically rationalized his behavior. Like, even though what he was doing was definitely illegal poaching, he was killing bucks, and not fawns or does. Or that the meat he was supplying to locals was his repayment for favors people had done for him. Yet, even the biggest local outdoorsmen disapproved because what he was doing wasn’t subsistence hunting—he was straight up slaughtering everything that moved and trapping animals far beyond his limit.

Retreat to Bull Camp

By the time 1980 rolled around, Dallas had become more extremist than ever and decided to really commit to living off the grid. No more trips to the Paradise Hill Bar, no more regular reliance on anybody else. So in a place just 2.5 miles north of the Nevada border and 13 miles east of Oregon, he decided to set up a camp that would keep his poaching operation with George Nielson going. It was a remote Idaho canyon right off the Owyhee River in a place called Bull Camp.

While friends from the Paradise Valley area would make semi-regular stops to restock him with fresh produce and other crucial supplies every few months, he basically lived out there fully off-grid, and completely alone for an entire year. One of them was this kinda bored local potato farmer on the brink of retirement named Jim Stevens, who would bring some of Dallas’ favorite treats like fresh oranges and butterscotch pudding his wife made.

The thing is, even though Bull Camp was on public lands, it was also acreage another Idaho family leased from the BLM for their cattle to winter on. It belonged to Don Carlin and his son Eddy, who ran and managed the 45 Ranch. Because being a full-time rancher was hard for a family to survive off of even back then in the glory days of being a cattleman, it wasn’t uncommon for ranchers to also be trapping, where they could earn a few extra bucks selling pelts to help supplement their families during the slow months. But these people usually did so on the up-and-up, and were actually following local game regulations.

The Carlin’s heard there was a mountain man living off and trapping on the land they paid to lease from the BLM, and on the brink of trapping season and when and where they also wanted to trap, Eddy Carlin rode out to Bull Canyon to meet this character and have a conversation about turf. He arrived to see what Dallas was up to, where he’d already had out-of-season pelts stretched out pretty much everywhere in sight. Vibes were sinister. It sounds like Eddy had a respectful, yet troubling conversation with Dallas that basically gave him the creeps. Claude acknowledged he was trapping ahead of the official season opener, and Eddy said he wasn’t going to spill the beans to anyone but that he knew game wardens routinely patrolled the area, and that they would eventually discover Claude and his camp. Now perhaps one of Claude’s most infamous quotes, Dallas replied that he’d “be ready for them.”

Naturally, this totally spooked Eddy Carlin. It was obvious to him the type of person he’d just met was one he probably wouldn’t want to make an enemy out of. He drove more than 50 miles for a phone at a nearby Indian Reservation to get ahold of Super-Game-Warden, Bill Pogue to raise a flag about other illegal poachers on their land, but specifically left Claude Dallas out of the conversation, basically anticipating this guy would definitely be trouble, and didn’t want to send the conservation officer straight to him.

Bill Pogue was the former sheriff of Winnemucca, and had spent his entire career in law enforcement. When researching this story, I read a book called Give A Boy A Gun by Jack Olsen, which described Pogue as the personal body guard for any wildlife in the area. He was a seasoned officer who held people to the law, and realizing how far Eddy Carlin drove for a phone to reach him, he took this tip-off seriously and immediately called in his much younger partner, game warden Conley Elms to accompany him in the field.

Murder on the Owyhee

On a cold, wintery morning in a remote canyon deep within the Idaho-Nevada state line, Idaho State Game Wardens Bill Pogue and Conley Elms arrived. It was January 5th, 1981. Just before they showed up to see who exactly was on the 45 Ranch and the other end of Eddy Carlin’s cautionary call, another person had also arrived at Bull Camp: Jim Stevens, Paradise Valley potato farmer, and one of many community members who decided to take Claude Dallas under his wing. Only a few days after the holiday season and into the new year, Stevens showed up to restock Dallas’ supplies.

Basically distracted by Stevens’ visit, Claude was down at his camp when Bill Pogue and Conley Elms arrived up near the mouth of Bull Canyon. But having studied every sound and tracked every movement in this isolated canyon for more than a year, he detected their presence the second they arrived. And of course they not only saw a bunch of illegal traps baited all over the freakin’ place, but could also very clearly see what Claude Dallas was up to was no good, with many out-of-season bobcat pelts stretched out and multiple deer strung up around his camp.

A fierce defender of animals and the laws that protect them, Bill Pogue basically immediately approached Dallas, and wasn’t in the mood to listen to any of his BS. Conley Elms on the other hand was much softer spoken, but also a lot bigger in size and perhaps more physically intimidating — at least that’s what I pictured from all the articles I read about these two Idaho Conservation Officers. After a few terse words, they basically informed Dallas that, based on all the illegal shit they could see happening all around his camp, that they were not only going to cite but arrest him, and were also going to disarm him and search inside his camp. They did take one of his guns away from him, a 357 Ruger security-six revolver, but failed to see he also had another one strapped to his hip, concealed beneath a long cowboy duster coat.

Nobody exactly wants to be arrested, but with his worst fear realized, they cornered Dallas in front of his camp with his hands behind his back, threatening to enter his tent and also handcuff him (another major fear of Dallas’). And by the sounds of it, all it took was an instant. While Stevens had his back turned to them and was overlooking the Owyhee, Dallas crouched down and grabbed his revolver, shooting both Pogue and Elms back and forth before Stevens could really even react. And as they lay there dying, Dallas would return to his tent for his .22, only to shoot each of them behind the ear and the exact kill shot that would put one of his trapped animals out of its misery.

And what a world of hurt this put Jim Stevens in, who thought he was just coming to see an old friend and became an innocent bystander with the quickdraw of a gun, fearing maybe Dallas would now aim his crosshairs at him. But, it was just the law and its messengers that Dallas had a problem with, and not his old friend Jim Stevens. In that book I read, Give A Boy A Gun, it described Dallas justifying gunning the wardens down by proclaiming Pogue and Elms did a sloppy job of regulating the laws, they had it coming, and deserved it.

From here, things got really complicated for Claude Dallas. In the book I could really feel his perhaps instant and only regret was involving Jim Stevens. Dallas both implicated him by murdering two game wardens then basically demanded his help in order to move and hide their bodies, while also coming up with an alibi that would get Stevens out of this jam. They dragged Elms’ body, face down and downhill to the Owyhee River, and loaded Pogue up in the back of Stevens’ truck. Then they cleaned up the camp a bit basically only to try and disguise bloody spots on the ground, and set off into the night for one place and one place only: George Neilsen’s Paradise Hill Bar.

The 15 Month Search for Claude Dallas Begins

The second Claude Dallas showed up to his bar in the middle of the night with a very rattled Jim Stevens and a dead cop in the back of his truck, George Neilson didn’t seem to want to have anything to do with him. Well, kind of. According to this book Give A Boy A Gun, which I sometimes couldn’t find the line between truthful events and narration for a plot line’s sake, the three of them unloaded Pogue’s body out of the back of Stephen’s truck and into one of Neilsens. And as Claude disappeared with Pogue to hide his body in a coyote den near Winnemucca Dunes, Nielsen and Stevens burned their clothes and Stevens went home, trying to wrap his mind around what he would say to authorities in the looming morning hours.

That left Nielsen to deal with Claude. When Dallas returned, Nielsen didn’t ask and didn’t want to know where he had buried the game warden—again, according to this book. Instead, he dropped him off somewhere near Sand Pass Road, which connects from Winnemucca Dunes up to Highway 140, or the road to Denio. Claude vanished into the night, and that was the last anybody saw of him for 15 months. At least anyone looking for him.

Just as quickly as he disappeared was about the same amount of time it took for Dallas to become an overnight folk hero, instantly creating the Legend of Claude Dallas, and a major migraine for every cop within a thousand miles. While Stevens and Nielsen reported their traumas to the police in the morning, anyone who knew Claude believed he could’ve probably made it all the way across the Black Rock Desert on foot by morning. Ultimately, thousands of law enforcement officials and just as many volunteers would scour the high desert for a little longer than a year and a half, tirelessly searching on foot, by air, and with dogs. They dredged reservoirs and hot creeks, drilled into iced-over lakes, and chased down leads that put Claude Dallas in the Yukon and the tropics in the same hour. All of them were dead ends.

The Owyhee turned out to be the perfect hiding place, with no better person to know every square inch of it than Dallas. People who knew him believed he had at least seven camps somewhere out there, each stocked with food, guns, and lots and lots of ammo. Locals throughout the region were said to have left pickup trucks out every night with keys in the ignitions and full gas tanks, and beers and sandwiches in the cooler. Northern Nevadans and Southern Idahoans even made t-shirts that boasted “Go Claude Go”. Every waitress and cowhand from Reno to Boise knew the story, and as the book described, he was a person that was everywhere but nowhere all at the same time.

People in the region and many parts of the rural West basically freakin’ loved that he stuck it to the law, not allowing anyone to tell him how to live his life when he “wasn’t hurting anyone”. On the other side of the coin, just as many folks stood by law and order and those responsible for enforcing it. I guess that really just goes to show that you could know of a person without truly knowing them, or what they’re capable of.

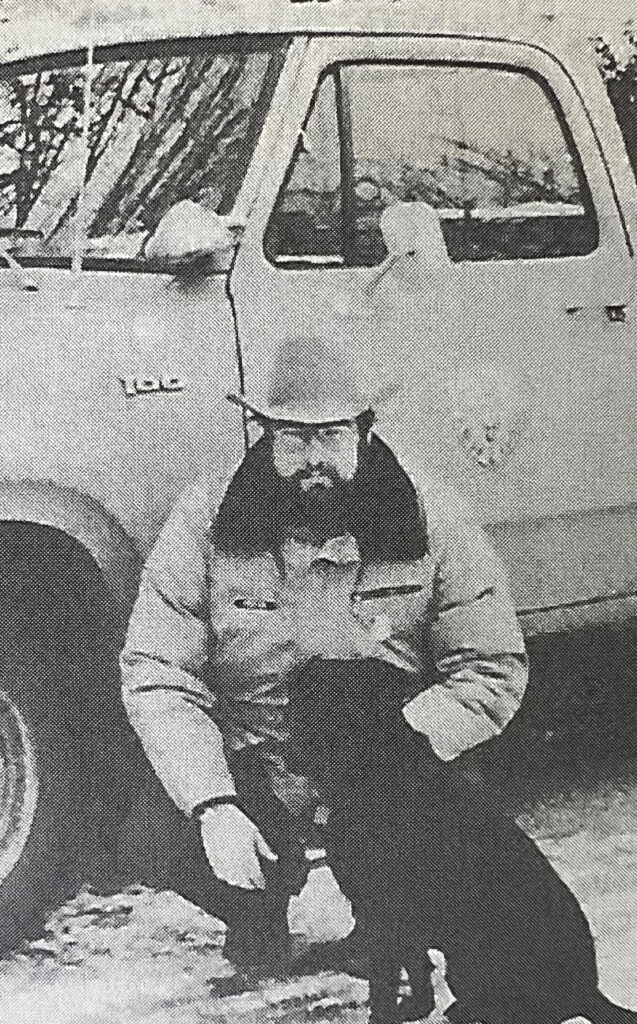

Claude was on the run from January 1981 to April 1982—fifteen whole months. His escape route brought him w est of Sand Pass Road and through the Black Rock Desert, over to Mendocino, on to South Dakota and where he was said to have worked a job undetected by simply scrambling up the digits of his social security number, down to Texas, back up to the Alvord Ranch, and ultimately back into north central Nevada. Apparently he returned to Paradise Valley, where his presence was reported on a tip line to the FBI. You better believe just about every law enforcement agency within 500 miles was part of that raid and arrest, but it was FBI Special Agent Franz Nenzel, SWAT officer Dave Gillian, and Owyhee County Sheriff Tim Nettleton who led the teams responsible for capturing Dallas.

Naturally, he didn’t go down without a fight, where he basically escaped the house they surrounded and jumped into a pickup truck equipped with several loaded weapons. In the book I read, it described Dallas shooting at helicopters closing in on him while blasting down a Paradise Valley dirt road. He was shot in the leg, crawled into the sagebrush, and was ultimately found, cuffed, and booked. His worst fears realized.

The Trial: They Both Reached For the Gun

Just about overnight, locals in the region raised the Claude Dallas defense fund while also quickly forming the narrative that both wardens had a major attitude problem, painting them as overbearing, ruthless, and antagonizing. Bullies even, who played with their guns. They believed that Dallas did what a lot of people would do, and deserved a medal instead of jail time, and that Pogue was a pushy man, and Dallas was the type of man you don’t push.

On top of all that, a lot of locals to the Paradise Hill region started fixate over who the hell tipped off the FBI, forming this sorta pseudo manhunt of their own, and with the trial in Idaho (where his crime occurred), even obsessed over which state Bull Camp was located in and made sure maps and boundary lines were actually accurate. And, aside from the majority of his defenders also living in the ultra rurals and personally identifying with Dallas’ way of life, a whole other sympathetic fan base emerged: twenty-something women who basically saw him as this super attractive, new outlaw in the old frontier. They were called the Dallas Cheerleaders by media covering the case.

Meanwhile, Pogue and Elms’ widows, along with just as many defenders of the law as those tearing it apart said the wardens were upstanding emblems of the law. They argued that two different people were on the stand: the one at Bull Camp that early January morning and the one before them in the courtroom, and that every game warden in America may as well be walking around with bullseyes on their uniforms if they were to let Claude go.

The jury was made of 10 women and 2 men, and were instructed to follow the law and not their emotions—which was ironic to me personally, seeing as Dallas did the exact opposite. It became the longest case the judge had ever presided over, and also became the longest case in Idaho history, with more than 80 character witnesses that both defended and tore Claude and the Idaho game warden’s characters apart. My eyes almost popped out of my freakin’ head in one particular section of this book I read, when the Waddie Mitchell showed up as a character witness for Claude Dallas.

If you know him, he needs little introduction—he’s a Nevada icon. And if you don’t, he’s basically among Nevada’s most famous buckaroos, who lived and worked on many of the Great Basin’s largest ranches and is a founding member of the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering, which happens in Elko every January and celebrates cowboy life, culture, and tradition. He not only worked alongside and even shared a tent with Claude Dallas, but even vouched for him as “the best cowboy in Nevada”. Having a hard time basically finding the line between truth and narration in this book more than a few times, I contacted Waddie to confirm this was true: it was.

To me, the biggest part of this case that really set everyone off was the bullet behind their ears, and whether this was a cold-blooded execution, or an act of humanitarianism by putting them out of their misery. Dallas claimed that Pogue rested his hand on his pistol during the confrontation, which is what a lot of law enforcement will seem to do when speaking with you—the whole hands on the utility belt thing. Whether it was just a conversation or an actual threat and that Pogue would truly draw his weapon and shoot Dallas over poaching, I guess we’ll never know—we weren’t there.

One of the jurors—who sounded like the only one who wanted to actually charge Dallas with murder one and not involuntary manslaughter, was ultimately dismissed for having preconceived opinions about Dallas before the trial began. Their replacement would agree with Dallas’ defense, in that he was protecting himself from overly-aggressive and threatening lawmen. And while he was initially charged with two counts of first degree murder, his sentence was reduced to two counts of involuntary manslaughter.

This was a really surprising turn of events for me and many others, who believed reducing his charges to manslaughter really minimized what he did. But what shocked me even more was that a $100k bond was posted for Dallas, and then immediately raised and paid by his supporters. While he was awaiting sentencing, they busted him out of the joint and brought him to a private hunting camp in Paradise Valley. It sounded like he visited and stayed with many old friends in the region, but also instantly returned to a way of living he knew and loved: in open violation of game laws.

Dallas’ Sentencing, and His Second Escape

Then the day came for his sentencing, on January 4, 1983. The crazy part is, between his conviction and sentencing which was a few months time, jurors were threatened, and even Judge Edward Lodge’s dog was shot and thrown on his own lawn. During the sentencing, the judge opened by acknowledging Dallas was clearly beloved, but that no question of self-defense actually arose. That, and two state game wardens would never shoot someone over a misdemeanor in the first place, let alone in front of another witness. He said Pogue and Elms believed they had disarmed Dallas, and that Claude fired and hit Pogue before he even drew his weapon and if he were to believe it was self defense, Dallas wouldn’t have run, or loaded his weapon to protect himself. That, and by instructing Stevens what to do next to help him proved he was in the defense, not offense.

Dallas was sentenced to 30 years. Sounds like the only emotion he showed throughout the whole deal was at the end of his sentencing, when those handcuffs were clasped around his wrists. He later filed an appeal in 1985, and lost.

Then? Then this story manages to become even more mythic when Dallas escaped from Kuna, Idaho State Prison on Easter Sunday in 1986. He was on the run, again, for almost a full year before eventually being caught outside a 7-Eleven in Riverside, California in 1987. He was sent to prisons away from the West in Nebraska and New Mexico, and finally moved to a more high-security prison in Kansas. But get this: he would only serve 22 of his 30 year sentence, and was released 8 years early for good behavior in February of 2005. He’s still alive, said to be living in another really remote region of northeastern Utah called Grouse Creek, and the wilds of Alaska.

Protecting Your Paradise

Having traveled to many of Nevada’s far-reaching corners for many years and having spent time in plenty of rural bars including Paradise Valley, I knew what an unpredictable tale this was. I tend to be pretty tight lipped about most controversial subjects, and well, let me put it to you this way: I’ve done more smiling and nodding than talking out in Nevada’s ultra-rurals. There are a lot of topics that can be very touchy out there, but I guess I wasn’t fully able to grasp just how sensitive and polarizing this story was back then and still to this day until researching it.

Its extreme controversial nature also came into clear focus when I was able to ask a few friends who were alive and in the region as this happened, real time. It really put a lot of things in perspective for me because as much as I could study both sides of this story, the fact of the matter is, I wasn’t alive as this happened, and was only a baby when he was recaptured from his prison escape. A lot of my friends compared it to the Bundy ordeal that happened just a few years ago that I was alive for and of course saw the headlines unfold myself. Let’s just say that comparison alone gave me a lot to think about.

Basically, everyone I spoke with (including Waddie Mitchell) didn’t want to comment on it, speak anonymously, or stay out of it altogether, which told me almost everything I needed to know in a split second. This was a person whose life conflicted with the government, and not only rustled something awake in thousands of people across an entire region, but also inspired many books, songs, and even a movie. He was a hero and a villain to many.

One person I spoke with cowboyed the same region during this same time frame as Claude and discovered a wild mustang that had been shot one day out there on the range. Kinda puzzled by how bizarre this was and perplexed by who and why someone would do something like that, his campmates told him it was the handiwork of Claude Dallas. They also said that these stretches of a mostly unpopulated West fostered the lifestyle and dreams of plenty of seedy characters. Another person I spoke with spent a lot of time in this north central region of Nevada during the 80s, staying at many ranches filled with many people on Dallas’ side. Their brother was also a game biologist for NDOW, and personally knew one of the wardens who were killed.

So, was Dallas a remorseless, cold-blooded cop killer driven by delusions of a distant era? Or was he out there, not really bothering anybody, living life as he wanted in an out of the way place? The thing I keep coming back to is this: not everyone has the courage to dream about someone they want to become and then actually go out there and do it. But just because you actually go to those measures and declare yourself as such doesn’t put you above the law. He may have been chasing his dreams and defending his right to live in that remote canyon in the Owyhee, not hurting anybody up until he did.

I have a lot of strong feelings about the world I’m able to freely and regularly access out there in Nevada wild—one that’s available to me pretty much whenever and wherever I want to go, and as long as I’m not breaking any laws, without anyone really telling me what I can and can’t do. I know I’m unalone when it comes to this relied upon escape. And whether that means buying a piece of property, or keeping up with what we’re currently doing and heading out there every spare second we’ve got, we talk a lot about how we can both prolong and protect these feelings, and our ability to keep on accessing that magic.

How far would I go to safeguard it? I’m not sure, but as I read and finished this book out in some of Nevada’s most isolated places—the ones Claude became so fascinated by—it sure has given me a lot to think about. I wonder if I know anyone who personally helped Claude Dallas through the years. That, and if there will ever be a day where we might cross paths out there, bumping down the wilds of the Big Empty, and in the heart of the same country we love the most.

Note From the Author: the true story of Claude Dallas is based on researched, alleged facts. and just the same as all legends of lost Nevada stories, includes personal opinion.

Sources

- The visual presentation of this story would not be possible without the generosity of Scott Moritmore, who graciously provided images from his personal archive. See more of his work (and life exploring the Great Basin State) right here. If I haven’t sold you on Nevada, with one look at his work, you will be now.

- “45 & Star Valley Ranches, Owyhee County Idaho”, Hall and Hall, 2020, https://www.legacysite.landbrokermls.com/members/documents/propdocs/2623_1591726393.pdf

- “Claude Dallas”, Alchetron, November 18, 2023, https://alchetron.com/Claude-Dallas

- “Claude Dallas”, Wikipedia, June 17, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_Dallas

- Cornelius, Jim. “Claude Dallas” Frontier Partisans: The Adventurers, Rangers, and Scouts Who Fought the Battles of Empire, September 15, 2015, https://frontierpartisans.com/4481/claude-dallas/

- Croke, Bill. “The Cowboy Poet and the End of the West”, Washington Examiner, September 2024, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/magazine/1919432/the-cowboy-poet-and-the-end-of-the-west/

- McDowell, Bart. Photographs by William Albert Allard. 1972. The American Cowboy in Life and Legend. The National Geographic Society.

- Mooney, Bill. “The Circle A Ranch of Nevada”, Cowboy Showcase, December 21, 2009, https://www.cowboyshowcase.com/mooneys-stories—the-circle-a-ranch-of-nevada.html

- Olsen, Jack. 2024. Give A Boy A Gun. Las Vegas, NV. Crime Rant Books.

- Riley, Michael. “In Idaho: A Killer Becomes a Mythic Hero”, Time, January 26, 1987, https://time.com/archive/6708158/in-idaho-a-killer-becomes-a-mythic-hero/

- “State v. Dallas”, From Casetext: Smarter Legal Research, November 20, 1985, https://casetext.com/case/state-v-dallas-16