Prefer to hear to this Story Instead? Listen Here.

It’s the perfect place for secrets, this state.

It also just so happens to be the perfect venue for wondering what’s off in the distance way down there or when it was the last time someone stopped by, and then actually having the public lands access and the will to go find out for yourself. At least, that’s exactly what a group of 30-something Ely-area cavers did in the early 1980s, after being tipped off about a possible limestone cave hidden deep in eastern Nevada’s high country.

And sure enough, in a lone mountain range mere miles from the Loneliest Highway, Ely’s High Desert Grotto caving club would go on to not only set foot in a place no other modern man ever had before, but they would also discover the most complete skeleton of the largest carnivorous mammal ever reported in the continent: The Giant Short-Faced Cave Bear.

And from trying to figure out the largest cluster of natural caves in Nevada from the speleological pros, to connecting with the same guys who wiggled into that waterlogged cave back in ‘82, to realizing the force of this ancient superbeast twice the size of a grizzly bear, to unpacking the Pleistocene timeline and Nevada’s prehistory with paleontologists responsible for excavating the cave then safeguarding its ten thousand year old remains, I realized there are lots of layers to this story. Just about as many as the sediment in which these remarkable ancient fossils were discovered, in fact, and those that would ultimately change the way we think about Nevada’s prehistory. It’s the legend of Lily the Giant Short-Faced Cave Bear, and the team of people who were courageous enough to find, protect, and preserve her place in a world that always seems to be changing.

Nevada Caves

Caves, man. Nevada’s got ‘em—a lot of them. At least when it comes to the eastern side of the state, where Nevada’s largest concentration of natural limestone caves awaits. And you know, the more I spend time staring at mountain ranges from my ultra rural camp setups out there, trying to spot cool features or something that moves, the more I realize how much I’m fascinated with Nevada caves. Knowing something is there that you can’t see right away really has become the center of my Nevada intrigue, and the more I think about it, there really is no truer emblem of those sentiments than Nevada Caves.

If you can spot one on the mountainside way up there, well that’s one layer of satisfaction. If you’re able to figure out what’s inside, it’s another completely different thing. Within, there might just be the best example of pictographs in North America, a cache of Tule Duck Decoys, a California Trail pioneer’s hidden axle grease inscriptions, ancient canine burial sites, or in this case, the most complete remains of this continent’s largest predator. And boy, what a lair this cave must’ve been ten thousand years ago, overlooking a valley that doesn’t look much like it does today.

But wait, how do all these Nevada caves form and why are there so many of them in eastern Nevada? Well, in a place that was mostly covered in massive sea-like bodies of water long ago, many Nevada caves were formed by wave action, or when water crashes into mountain sides that over time, would carve out a natural cave. But in eastern Nevada and where this story takes place, so many natural Nevada caves exist because of their limestone geologic makeup. That, and a lot of tectonic activity. Nevada’s eastern edge has the state’s largest number of caves in general, which are considered special in terms of both hydrology and geology.

The way I understand it, when slightly acidic groundwater seeps through cracks in limestone bedrock, it gradually dissolves it, creating cavities that can eventually become caves. When this happens, it’s called a karst formation, and over millions of years time, it can create something as grand as Carlsbad Caverns. Or Lehman Caves, which is the largest and most celebrated cave in Nevada thanks to its size and number of intricate features like stalactites, stalagmites, columns, and shield formations. Lehman Caves is situated in the Snake Range just about as far east as you can go and still be in Nevada, nestled deep within and protected by Great Basin National Park.

The park—Nevada’s only national park, by the way—has 41,000 acres of karst landscape that supports a lot of caves, which is what keeps groups like the National Speleological Society so damn interested in eastern Nevada. As the largest caving-focused membership organization in the world, it’s their mission to promote fellowship among cavers and to protect, explore, and study caves. What a venue they’ve got, right here in Nevada’s Great Basin. This cluster of caves is also what ultimately captured the attention of Great Basin National Park Ecologist Gretchen Baker, and what would become her life’s work.

I’ve been lucky enough to know Gretchen for a long time, and was excited to talk with her about Nevada Caves and the Giant Short-Faced Cave Bear knowing she’d almost certainly been inside the cave these amazing remains were discovered in not so long ago. Gretchen landed in Great Basin in 2001 after spending time studying the Everglades, Yellowstone, Carlsbad Caverns, Glacier Bay, Death Valley, and Jewel Cave. She estimates she’s been inside around a thousand separate caves throughout her career, and has studied even more.

Gretchen told me we’re living in the golden age when it comes to Nevada speleology (or the study and exploration of caves) and especially in eastern Nevada, which is partly what’s kept her here for so long. Only within the last few years and thanks to an influx of federal funding, they’ve been able to better understand how these caves formed, who and what lived in them, new types of cave species, and how water previously or currently affects them.

Water in the desert has always been a magic thing. It’s also what led the Ely High Desert Grotto caving club right to the Giant Short-Faced Cave Bear.

Ely’s HIgh Desert Grotto & A Discovery of a Lifetime

Ely, Nevada—what a perfect place for a caving club. Back in 1982 and when this story all happened, hundreds if not thousands of eastern Nevada caves awaited the High Desert Grotto caving club’s discoveries, including the caves and karsts inside Great Basin National Park boundaries, which didn’t exist yet. That designation wouldnt come until four years later, in 1986. Imagine the possibility of real adventure that lay before them—the type you read about in books or see in the movies—practically right in their own backyards, and with very few restrictions or anybody telling them no.

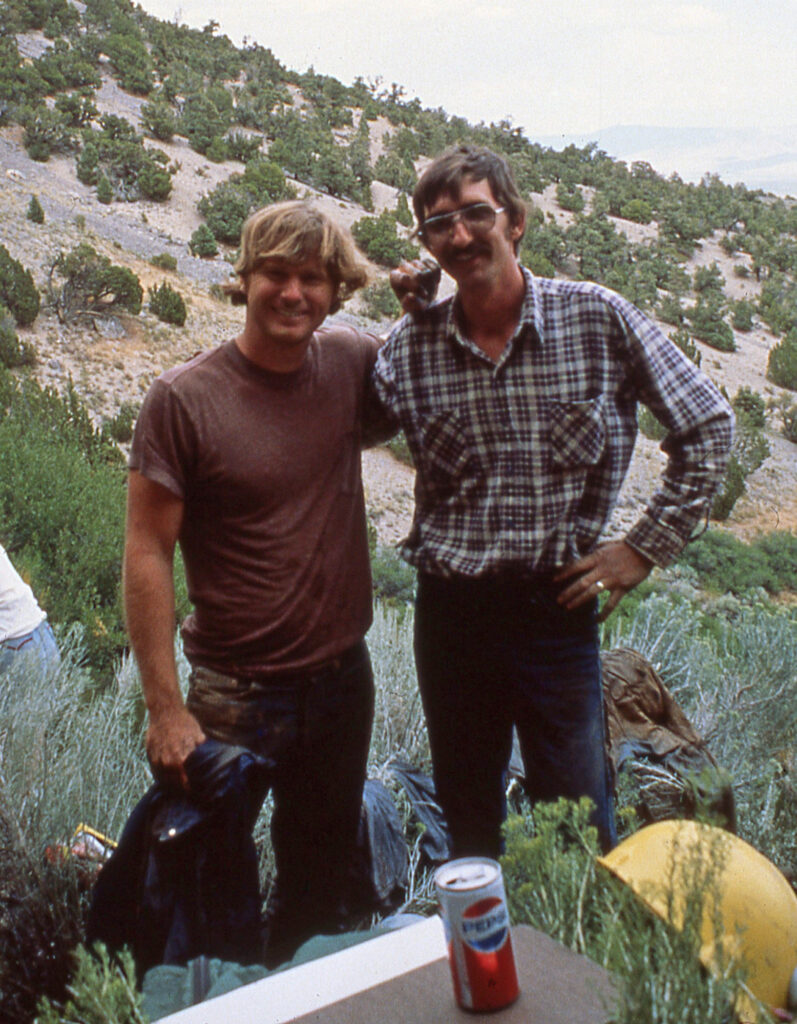

The original members of the High Desert Grotto club were mostly 30-something guys who all caught caving fever—and bad. From what I could put together, they spent as much time as they could backpacking, hiking, four-wheeling and experiencing the same high desert arena many of us Nevadans have become fixated with, along with spelunking into any caves they could find. I read through a lot of the High Desert Grotto club newsletters detailing the thrills of their many explorations, and besides getting into any cave they could visit, most of what threaded their interests together was making new discoveries, or accessing caves nobody else had mapped or visited. These newsletters, documenting their explorations crawling into barely noticeable entrances that opened into massive, ancient chambers really lit up all the corners of my imagination. If only I were born about 20 years sooner you can bet I would’ve been right there with them.

A couple of them were geologists by trade and National Speleological Society members, which helped connect them to folks at the Cave Research Foundation, like Ron Bridgeman who studied caves in the region during the 1960s, just a couple decades earlier. Ron tipped them off about a possible high elevation cave in eastern Nevada’s towering mountain ranges, suggesting something was surely there beneath a large limestone rock because water noticeably trickled from it. He hinted that the group should maybe go check it out.

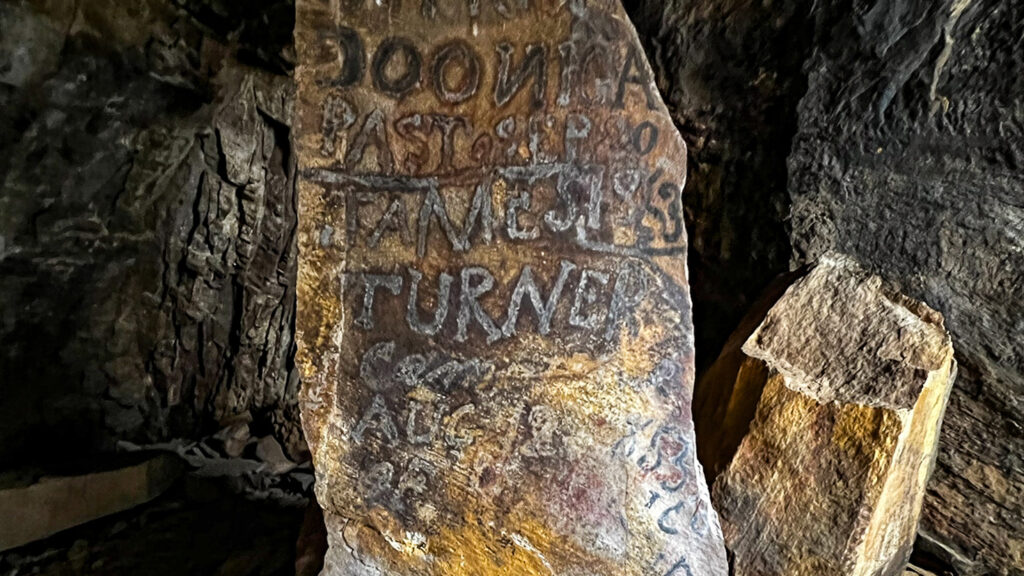

So on December 19th, 1981 High Desert Grotto Members “Spelunker Sam” Baker, Dennis Hone, Bob Swain, Glen Roberts, and “Limestone Louie” Echegaray jumped in their rigs and headed into the mountains in search of a possible undiscovered cave no modern man had ever likely realized, let alone visited. And surely enough, they located the site Ron was talking about, but decided they needed to return another time more prepared to be in the Nevada backcountry in the dead of winter.

So just about a month later on January 16th, 1982, the same group would return along with John Barnett, who was the group photographer and a main driving force behind the club’s official formation.

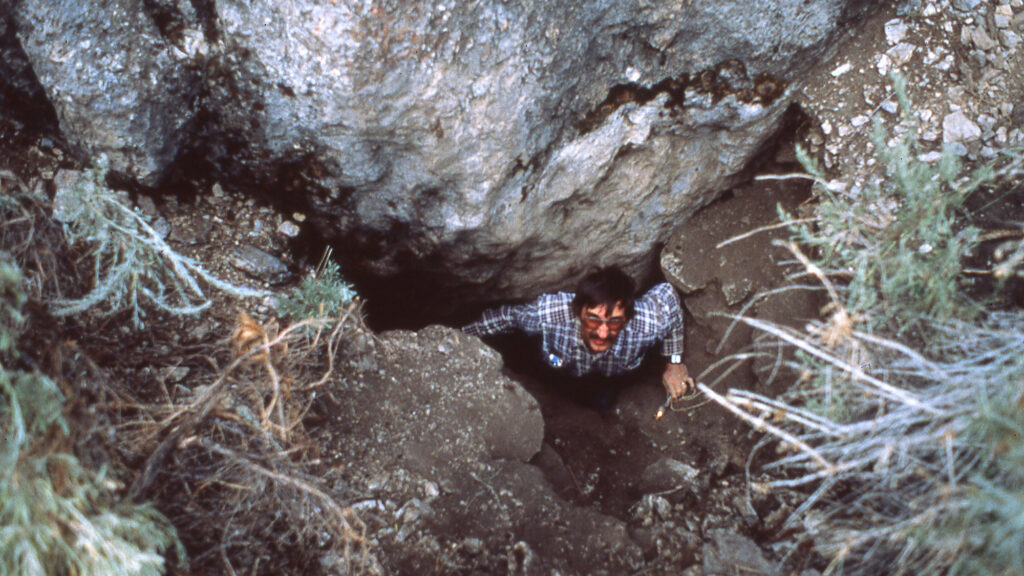

There on a frigid wintry morning at an elevation higher than the Lake Tahoe Basin at a limestone cliff hidden deep within the wilderness at the foot of one of Nevada’s tallest peaks, the group began digging. After several hours of shoveling and chiseling at an attempt to carve out a small opening big enough one of them could wiggle through, Glen Roberts made the comment that it would be a real labor of love to get into whatever might be below. And finally, the group created a chasm large enough for Dennis Hone to slide into—a feet-first shimmy into a narrow chute that would drop him into a frigid pool of water and into the cave, the Labor of Love Cave.

Freezing cold and soaking wet but over the freakin’ moon about this discovery of a lifetime, the group would return a third time the next day, January 17th, 1982, this time prepared to get each member of the High Desert Grotto into this narrow opening and deeper into the Labor of Love Cave. “What a beautiful winter day to be on an Eastern Nevada mountainside,” they recounted in their club newsletter. “Bright sun, with a deep blue sky; a large buteo hawk floating overhead, two feet of new powder snow on the north face of each ridge, and on the south facing slope, seven inches of slowly compacting snow, shrinking before a strong sun and fair breeze. We occasionally cross the tracks of a mule deer, seeing evidence of their browsing on the older stands of bitterbrush in the bottoms of the swales.” Dennis Hone wrote these newsletters for the group, and gladly sent them to me when I got in touch with him. Sure sounds like those days we all live for out there in Nevada wild, doesn’t it?

And one by one, each member slid down through the narrow opening beneath a giant slab of rock, twisting and bending beneath more rock faces before dropping into a small flowing stream. They described that first entry as three feet high by three feet wide, with a sloped passage tilted into the mountainside and several pools of water. As the group got their bearings inside this deep, dark, ancient cave, they noticed it opened up to be much larger at about 450 feet deep, extending far into the mountain. The group was also immediately dazzled by the cave’s intricately formed and extremely fragile stalactites and stalagmites within this totally active cave, which is how the pros describe caves that still have water flowing or dripping through them with active chemical erosion.

Then? Then they spotted the bones. Below the surface of cerulean pools of water, the High Desert Grotto members noticed what looked like the remains of something big. They wrote “Sam has spotted two sets of bones, partially and totally submerged in the water. Is the first set hominid? The other appears to be a large carnivore. These bones, in a sealed cave, might be of considerable age. In addition, the fragility and delicacy of the formations is astounding.” They would go on to discover even more large bones, deeper inside the cave.

I can barely wrap my mind around the thrill that must’ve come along with finding something like that, and from the sounds of it, neither could they. These nine members of the High Desert Grotto club sat deep inside the cave marveling at what they’d just discovered, belted out their clubcall in honor of this truly momentous occasion, and returned to the cave’s entrance where they celebrated with a bottle of champagne they’d buried in the snow just a few hours earlier.

Identifying the Giant Short-Faced Cave Bear

The second their tires gripped onto the pavement and they reached Ely city limits, the High Desert Grotto members got a hold of Ron to let him know he was right on target for predicting a possible cave, and began putting their feelers out to anyone who might be able to help identify this ancient jawbone. Ron made instant plans to visit the cave in the company of several pros like a professor of anatomy and an archaeologist, while other High Desert Grotto members divided and conquered by getting ahold of a couple different BLM archaeologists who ultimately suggested the jawbone could be from an ancient Cave Bear.

And luckily, this team of local, Ely-area experts would lead the High Desert Grotto to Steven Emslie, a freshly graduated paleobiologist just starting out in his career, and right around the same age as the other High Desert Grotto club members. Steve confirmed what they’d found was in fact the lower jawbone of the Giant Short-Faced Cave Bear—an animal that went extinct in the Pleistocene around 10,000 years ago, and was also the king of the food chain, yet one of the first species eradicated from the planet by humans. And as a slightly confusing aside and before we go any further here, there’s also such a thing as a regular old Cave Bear. But, make no mistake we’re talking about the Giant Short-Faced Cave Bear here. Know that they’re different, and whenever I mention a Cave Bear in this story, I’m talking about the Giant variety, of course.

By March of 1982 Steve became the lead guy in charge of the Labor of Love excavation, and as the discoverers of this ancient site, he let the High Desert Grotto members know they were in total and complete control of where the fossils would ultimately be stored and studied. Steve offered his help with one catch: that the High Desert Grotto figure out how to get a scientific collection permit. These were relatively rare and difficult to secure from the US Forest Service, but doing so would ultimately help connect the dots on our knowledge of animal and taxonomic relationship in the evolution of the bear family. If the club handled the permit, he’d get the grant money lined up that would fund the excavation.

Meanwhile, Sam Baker admitted to a recurring nightmare: that the bones within the Labor of Love Cave were stolen, slabbed and turned into bolo ties. So you could say protecting a freshly exposed ancient cave was riding high on the minds of the High Desert Grotto. By April and while Steve worked on the grant to fund excavation, Kenneth Byrd, an assistant professor of anatomy and cave research, concluded that all of the bones in the Labor of Love Cave ended up in there naturally, and were of “extreme scientific value.” That was what the group really needed to approach a place to store these ancient bones once they were safely removed from the cave.

And here’s where this whole thing really gets me: the High Desert Grotto first approached the Nevada State Museum—an obvious first institution to contact about ancient bones recovered on their turf. They ultimately had total disinterest in the find but also asked for $1,080 per cubic foot in order to store the remains. So, they went to the top fossil museum in the West: the Page Museum, which is now the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History and the La Brea Tar Pits Museum. Besides being one of the largest fossil sites in the world and most robust fossil museum collections and exhibits in America, there’s also a permanent staff here devoted to studying and managing vertebrate paleontology that Steve already had a great working relationship with. They also had the largest collections of Giant Short-Faced Bear material back then, and now.

A Labor of Love

So with a plan of where to store the remains once excavated, a US Forest Service scientific collection permit in hand, and the grant money to fund it, High Desert Grotto members Sam Baker and Bob Swain assembled with Steve Emslie in July 1982 to excavate the Labor of Love Cave. This time the opposite from frigid wintry conditions, the group would arrive to discover very high water levels from the spring runoff flowing inside the cave. And even though it was peak summer in the high desert, the group still needed wetsuits to prevent hypothermic conditions in a cave that constantly remains around 50 degrees.

Once the group was inside they were able to explore the entire single chamber cave, take a look at the perennial stream flowing through it, and examine a dirt wall originally believed to be limestone. From there and upon closer examination of that dirt wall, they were able to figure out that they weren’t too far below ground and that this section of the cave was possibly open at one time, but later collapsed, filling in that section of the cave. They also learned that the stream flowing through it would’ve slowly filled the cave with silt, washing in periodically and forming many layers. Any animals inside the cave would’ve become trapped, where they would eventually perish and become buried. The pressure from the silt would’ve been too great for some of the buried bones, especially skulls, which is exactly why they weren’t able to recover complete skulls of any kind from the Labor of Love Cave—just that lone lower jawbone.

And then, after thousands of years of silt filling the cave, the stream either diverted or broke through a new opening and began flowing through the cave. Deposits that would’ve taken centuries to form were then destroyed by erosion, with complete skeletons being washed out and redeposited to new places. Then sand and gravel bars formed, which contained hundreds of bones and fragments of many different types of living things.

When I connected up with Gretchen, the Great Basin National Park ecologist, she compared caves to big, cold, dark refrigerators, and that really stuck with me. She mentioned she’d been to the Labor of Love Cave site a few different times throughout her career, and of course knew this legendary site belonged to the Cave Bear. But she also said the cave stored a bunch of other species who no longer live in the area, like American Pika, Bison, Canada Lynx, American Lion, Shrub-Ox, and Harrington’s Mountain Goat. What an environment that ancient Lake Bonneville must’ve created. Definitely not the one we know today, anyway.

But, back to 1982. Emslie documented many slender soda straws, some three feet long, young stalactites and helictites inside this very active cave, along with the first bear skeleton they would discover, submerged in a pool. In a second pool deeper inside the cave, they discovered more big bones—both specimens washed into the cave from somewhere else, and likely were only preserved because they’d been in super cold water all that time. Steven Emslie would go on to write a lot of articles about this remarkable day, saying, “I knew I was about to embark on one of the most exciting experiences of my life. This turned out to be a gross understatement. My visit to LOL cave left me awed by its formations, and quite excited by the paleontological contents.”

Within two weeks, the team put together a plan to save the bones before they were washed away, or worse, stolen by vandals. They meticulously mapped where each of the bones were, how they were exposed, and completed a photo survey, carefully angling light into the water in order to capture the submerged fossils. Twenty people showed up to help, which happened August 1, 1982. Removing the bones took six hours, carefully wrapping each specimen in foil and noting its contents. And as they carried out the last two fossils and looked back on this ancient cave nobody had set foot inside for at least ten thousand years, they sealed the entrance behind them.

By September, their club member roster doubled.

Meet Lily: The Most Complete Short-Faced Cave Bear Ever Discovered

I had the rare treat of connecting up with the Steve Emslie this past December, which was a clear high point of my career meeting with people who’ve seen something in Nevada and gone to remarkable lengths to protect it. He returned my first email from Antarctica where he was doing field work (!!), let me know he collected a few more degrees since that summer of ‘82, and has been a professor in biology and marine biology at the University of North Carolina since 1998. I asked him, now that more than forty years had passed since that day in the Schell Creek Wilderness, if his Cave Bear excavation still remained one of his top career highlights. Steve said he’d had lots of other exciting moments and discoveries through the years studying Condors in the Grand Canyon, at fossil sites in Florida, and in Antarctica, but that Labor of Love cave entrance was pretty damn special.

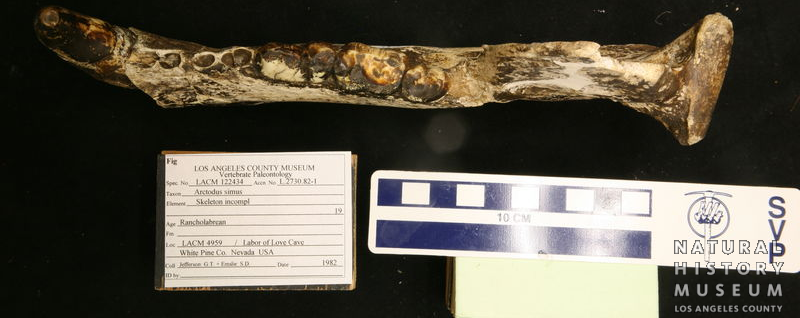

As a paleobiologist, Steve helped me connect the dots on exactly how special this discovery was and is, who the Giant Short-Faced Cave Bear really was, and what it all meant in redrawing the Great Basin’s prehistoric timeline. This Ely discovery was so important because it was not only the most complete Giant Short-Faced Cave Bear skeleton ever discovered, but was also the first time that one could be fully analyzed. Once Steve and the High Desert Grotto were able to remove the fossils from the Labor of Love Cave, they were shipped to the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History. From there, it took about a week to clean, preserve, and identify each specimen, which was a long, meticulous task, but proved more and more interesting with each passing moment. Right away, they were able to figure out this was a near complete female specimen they had on their hands, and one the White Pine Museum would eventually call Lily.

So, who was this Legend of Lost Nevada? Well, in short, take whatever modern giant bear you might be imagining, like say a Grizzly Bear, and then double it in size and weight. On all fours, the Giant Short-Faced Cave Bear could stare a 6-foot person in the face, and when standing on its feet, it towered over 11 feet tall. Males were capable of weighing up to 2,000 pounds, while females like Lily were around 1,100. In other words, these were the largest known terrestrial carnivores that ever existed on this continent, roaming all of North America during the Pleistocene 2.5 million to 12,000 years ago.

Lots of Giant Short-Faced Cave Bear skeletal remains have been found all across this country in places like Alaska and the Canadian Yukon, in California, Wyoming and Nebraska, the swamps of Florida, and even Mexico. But what happened at White Pine County’s Labor of Love Cave is so damn special because it’s mostly complete, but also the first ever record of this species in Nevada.

When researching the many layers of this story, I got the chance to read a lot of different materials about the Giant Short-Faced Cave Bear, including a book called Chasing the Ghost Bear: On the Trail of America’s Lost Super Beast by Mike Stark. He mainly wrote about another Cave Bear recovered from the Mt. Shasta region of northern California at Potter Cave. And while his book and other materials I thumbed through may have suggested the Cave Bear’s bone crushing teeth and fearsome claws meant this creature was a super predator and ready to shred anything’s face off that moved, it’s here’s where Steve’s work differed (with the help of Nick Czaplewski), and was a scientific opinion that honestly outraged a lot of people. At least, at first.

You see, the largest terrestrial carnivore today is the African lion, but herbivores like elephants can grow to be such mighty sizes because they essentially have a more flexible plant-based diet. And so for the first time ever, Steve theorized that the Giant Short-Faced Cave Bear was not exclusively this vicious skull-crushing beast, but an omnivore, relying on a largely herbivorous and opportunistic diet. So basically, in order for this ancient bear to reach such colossal sizes, it needed to have a stable diet and abundant food, meaning that it would eat whatever it could get: both plants and meat. They were predators and scavengers.

Steve was able to reach this conclusion by studying the Labor of Love Cave’s remains, and also realized that it was probably such an adaptable species because it had to be. This giant lived during the Pleistocene and ultimately became extinct due to a warming climate, which would disrupt access to any vegetation and prey it would rely on as food. The Cave Bear had a disproportionately short snout and scrunched face compared to modern bears, with bigger teeth and longer limbs, and a slender, cat-like body. Researchers believe that their legs evolved to be longer for prolonged, migratory travel, and also increased their vision over tall ground cover in an open habitat to spot food sources more easily.

So when Steve was really able to analyze the Ely Cave Bear’s specimens, he got to take a closer look at limb proportions, tooth size and wear, body size, and later, stable isotopes. He concluded the fossils recovered from this Nevada cave belonged to SIX bears instead of the two initially anticipated. This included multiple black bears, a tibia from a Grizzly, and one bone from a Short-Faced Bear not related to the other one found upstream. Altogether, there were the remains of three different black bears, two short-faced cave bears, and one possible grizzly, though the grizzly was likely carried in there by another animal as its deliberate or scavenged prey. So it was a cave of ancient bears, all mostly cohabitating, which connected some unanswered questions about interactions between bears during the Pleistocene, and all right here in Nevada.

He told me that the bones in the pools of water were not that well preserved and that they were most likely submerged for 10,000 years, or since the Pleistocene ended and melt streams would’ve been the highest. Once the cave sealed up and remained a constant cool temperature inside, it probably helped with their preservation integrity, too. Even though they of course excavated the Cave Bear’s fossils in the early 1980s which connected a lot of clues, it wasn’t until 2018 that more fossils suddenly appeared and this time outside the sealed cave’s entrance, prompting a continuation of this important work, this time with even more resources.

This all happened when USFS employee Doug Powell noticed there were more fossils scattered outside the Labor of Love cave while doing routine field work, which turned out to be ribs, bones from a foot, a shoulder, and a scapula. The discovery prompted Steve to return to Ely, this time with many more sophisticated tools than what was available 36 years earlier, like radiocarbon dating the Cave Bear’s teeth from some collagen still intact inside, protected by a shell of enamel. This would confirm what they believed all along: that the bones were deposited inside the cave before and during the Last Glacial Maximum (or Ice Age) and eroded from stream deposits inside the cave, and even though the entrance closed up in a modern world, it was very open, and very accessible to a lively valley below back then.

It also authenticated a pretty dreamy prehistoric visual, in a basin that’s almost completely dry today. Steve told me that during this time and back when the Cave Bear would’ve been roaming about, the region that’s now eastern Nevada was a very rich and diverse environment, with Bristlecone pine forests stretching down from those far reaching peaks and into the valleys, and lush, pluvial lake filled basins similar to the Ruby Marsh today, and lots of extinct megafauna within. Think of colossal giants we can only dream like the Cave Bear, camel, and giant sloths, but you would’ve also found plenty of other creatures like the Pronghorn Antelope, bison and horse down in the valley, with mountain goats clinging to cliffs, and giant teratorns, condors, and eagles soaring overhead. He said it must’ve been quite the site for early humans, this valley, and he’s right. At least my mind went completely wild envisioning this amazing, ancient scene.

There’s never been a mammal like the Giant Short-Faced Cave Bear in the continent before the Pleistocene, and there hasn’t been one since.

At the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History

I knew of the Ely Cave Bear and had seen the replica skeleton inside the White Pine Museum, but it wasn’t until I was standing in the paleontology department of the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History that the significance of this story would fully register. I guess having the lead vertebrate paleontologist pull that ten thousand year old jawbone out of a drawer and hold it right in front of you will do that to you.

But that’s exactly how it happened, once Steve graciously connected me up with Sam McLeod at the LA Museum. He’s the same guy Steve had a great working relationship with back in the 80s, and as soon as the Nevada State Museum shot them down, he got Sam on the phone next. And 44 years later he’s still protecting these ancient remains, and somehow instantly agreed to show me and my family what was inside those many rows of ancient archives. And that hour that we got to spend with him there? My husband compared it to getting to see the inside of a treasure chest. High above the droves of people downstairs in very crowded exhibits of gemstones, fossils, and taxidermied creatures from around the world, we walked rows of archives with America’s ghosts.

Out of one drawer he would pull out the hair from a bazillion year old giant sloth, from another an almost microscopic ancient mouse bone no bigger than a grain of sand mounted to the top of a pin, and entire cabinets brimming with tiny, prehistoric horse hooves. He even showed us a bunch of enormous bones recovered from the world famous La Brea Tar Pits right down the road, that all this time later, still smelled like tar. The place and the company was truly unforgettable. I honestly still can’t get my head around it, being part of Sam’s world that Friday morning.

Like aisles at a grocery store pointing out loaves of bread or cans of soup, each row in the LA County Museum’s paleontology department also indicated where all these cabinets of America’s prehistory came from. We spotted a lot of Nevada locations, like the Virgin Valley, Tonopah, Fish Lake Valley, Tule Springs, and of course White Pine County, Nevada. We were deep in fossil land when Sam pretty casually opened yet another drawer, this time holding out that jawbone. The one I’d never seen before—not even a picture of it yet—but I immediately knew was Lily’s.

As we crowded around this drawer of Giant Short-Faced Cave Bear fossils with Sam, looking at that still-intact tooth on the lower jawbone Sam Baker stored in his freezer all those decades ago and then Steve would radiocarbon date, all the things I’d bent my brain in two for these past couple months all started playing back, almost like a movie reel. Getting all the way down to LA to see Sam, downloading Steve and Gretchen’s expertise, meeting with and learning the story of the High Desert Grotto Members, and of course now seeing Lily herself. She was the main, yet final character I would meet in her own story. The last piece.

I’ve been to a lot of museums, but the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History was easily the coolest museum I’d ever set foot in. My friend and favorite pen pal John Ekman, who’s also the president of the Goldfield Historical Society, conveniently lives in LA and was also able to join up with us. I could’ve spent days here, but we at least got to spend a few hours where we would ultimately stumble upon an exhibit devoted to the Giant Short-Faced Cave Bear, and only because they protect its largest collection of fossils in the country. Here were the modeled, replica remains of the same fossils upstairs we were just looking at, with Sam.

In the Cave Bear Club

The Cave Bear museum exhibit in Ely became a thing after Steve’s radiocarbon dating realizations were made in 2018. That, and of course they wanted to commemorate the High Desert Grotto’s role in Nevada’s prehistory. One of Steve’s old friends Mary Beth Marks, who was there during the excavation in 1982, traveled to LA to help with the modeling of Lily’s original remains in order to create the exhibit at the White Pine Public Museum. And of course, when I got home from LA, the first thing I did was join the museum’s Cave Bear Club. About a week later, I got my club t-shirt, water bottle, stickers, and membership card. I’m member number 20.

Steve’s work brings him to all corners of the globe, and one of his main areas of focus is working on fossil birds. He told me that not too far down the valley from the Labor of Love Cave in other additional ancient caves, he’s continuing the work initiated by a group of archaeologists in the 1950s, studying the most abundant remains of prehistoric raptors beyond the La Brea Tar Pits. Besides the Cave Bear, these ancient wetlands in our Nevada high desert were also home to an impressive diversity of birds, like the Harlequin Duck, Snowy Owl, Greater Sage Grouse, and California Condor, which confirmed the first fossil records of these species in the Great Basin. He also discovered a new species of Kestrel. Caves of actual secrets, right here in a state that’s often skipped over altogether.

My husband and I have spent a lot of hours far away from people out in the Big Empty and this question comes up a lot: “Wonder who was the last person to stand on that peak over there?” we’ll ask each other. Or “who was the last living creature to stop by this exact place along the creek for a break?”, or “who stood in this exact spot to see this same view?”, or “how many people do you suppose have built a campfire right here through the years?”

If there’s anything we’ve learned from Lily the Cave Bear and the quest of her keepers it’s that someone or something probably has. That connection, bridging us in a modern world to a distant past, and all the life who have called Nevada’s Great Basin home through the millennia sure is a great place to let our minds wander. Now we don’t have to ask ourselves if, but when.

That bridge the High Desert Grotto forged between now and then is a true mind tangle for me. That, and the feelings they must’ve felt that day and in the months after: awe, satisfaction, and then probably a looming fear that what they’d uncovered could ultimately be destroyed if this information fell into the wrong hands. I can relate to that, at least on a much smaller scale. But that’s not what happened here, not for these guys. Besides this incredible find, maybe what’s most satisfying for me in this remarkable story is that at the end of the day, they could have their cake and eat it too—the paleontology was preserved, and so was the cave.

That, and no bolo ties were ever made.

Sources

- “Arctodus”, Wikipedia, December 14, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arctodus

- “Cave Bear”, Wikipedia, December 30, 2024,https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cave_bear

- “Cave/Karst Systems”, Great Basin National Park, National Park Service/U.S. Department of the Interior, December 2024, https://www.nps.gov/grba/learn/nature/cave.htm

- Dawn Andone, in discussion with the author, November 2024.

- Dennis Hone, High Desert Grotto Member, in discussion with the author, December 2024.

- Dr. Steven Emslie, Professor in Biology and Marine Biology at the University of North Carolina, in discussion with the author, December 2024.

- Emslie, Steven. “The Cave of Ancient Bears”, Terra, Vol. 23, No 4. March/April 1985.

- Emslie Steven and Jim Mead. “The Age and Vertebrate Paleontology of Labor-of-Love Cave, White Pine County, Nevada”, Western North American Naturalist, 2020.

- Emslie, Steven and Jim Mead. “Two New Late Quaternary Avifaunas from the East-Central Great Basin with the Description of a New Species of Falco”, Western North American Naturalist, 2023.

- Emslie, Steven and Nicholas J. Czaplewski. “Contributions in Science, A New Record of Giant Short-Faced Bear, Arctodus Simus, From Western North America With a Re-Evaluation of Its Paleobiology.” Lawrence, KS. Allen Press Inc., November 15, 1985.

- Gretchen Baker, Great Basin National Park Ecologist, in discussion with the author, January 2025.

- Hone, Dennis. High Desert Grotto Pit Bull Newsletters. January 6, 1981 through March 3, 1981.

- Joel Despain, National Cave and Karst Research Institute, in discussion with author, December 2024.

- “La Brea Tar Pits History”, Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County, December 2024, https://tarpits.org/la-brea-tar-pits-history

- Matt Bowers, National Speleological Society, in discussion with the author, December 2024.

- Sam McLeod, Collections Manager of Vertebrate Paleontology of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, in discussion with the author, December 2024.

- Stark, Mike. 2022. Chasing the Ghost Bear: On the Trail of America’s Lost Super Beast. Lincoln, Nebraska. Bison Books.

- Swain, Bob. “Notes on the Labor of Love Cave”, December 1982.

- Weiser, Matt. “Cave Bear Discovery Links to County’s Past”, White Pine County Nevada, December 2024.https://elynevada.net/cave-bear/