Prefer to Hear this story Instead? Listen Here.

To know something is there even though you can’t see it right away is my most favorite thing about Nevada, and proves true with all of this state’s best features. But add an unending tally of hot pools, and some of the largest geysers in the world to that quest and you’ll never not have my full attention.

As the most geothermally active place in the country and one of the most in the entire world, more hot springs sources await in Nevada than just about any place else. This country’s first people have treasured naturally occurring Nevada hot springs as sacred places for thousands of years, and while modern man has definitely impacted Nevada’s ruggedly remote landscapes to many varying degrees, visiting many of them makes it easy to forget what century you’re in. At least, the good ones. They’re the wild soaks, or those that blend in with Nevada’s rolling, high desert sagebrush steppe with not another soul in your 60-mile line of sight. They will always be my favorite kind. The kind I’ll never stop seeking.

But then there are others that were monumentalized in the Nevada history books as Historic Hot Spring Resorts. While the desert wilds swallowed most of them up long ago, there were once dozens of hot spring resorts all across Nevada from the late 1800s to the early 1900s when a national trend of relishing mineral purities of naturally occurring hot springs water came West. Resort hot springs once stood at Golconda and Buena Vista Valley to name a few, and even as recently as 10 years ago you could find five of these historic haunts across the Sagebrush State. Today only three remain.

But layered into Nevada’s steamiest thread of history is the fact that pretty much wherever you go or if you drill down deep enough, chances are you’ll find hot water. Then again, plenty of it gushes out of the ground too—both naturally and with intention—with some of North America’s most once-prolific, pre-exploited geyser fields out there in the Sagebrush Ocean, second only to the great and powerful Yellowstone National Park.

This is a subject that is real easy for me to derail on with hot water pretty much any place you go looking, but I’ll try my best to stick to the point here today with the legend at hand. It’s the story of the Great Basin’s dramatic geothermal activity, the tiny yet massive ecosystems and essential habitats they create, the crescendoing controversy of turning the earth’s heat into electricity, and Nevada’s many lost hot spring geysers.

nevada’s lost geyser fields

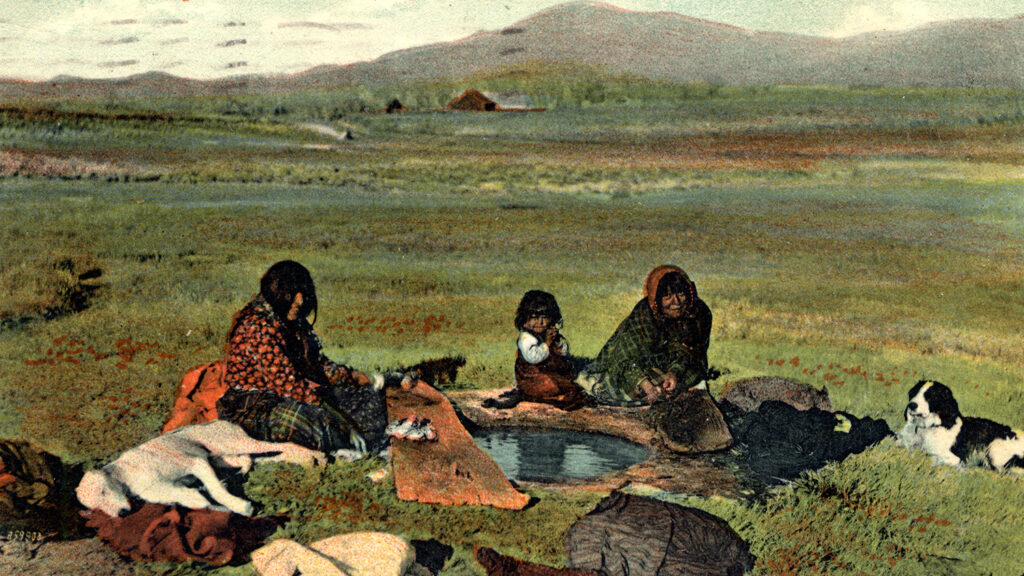

Nevada was once home to some of the tallest natural geysers in the country and world. It’s a freaky revelation that almost seems too unreal for even me to believe. And especially so knowing one of them once surged in the southern end of the very town I live in. But, that’s the natural origin story of Steamboat Hot Springs in south Reno if you can believe it, with so much seismic and geothermal activity it rumbled into an entirely different place. Well that, and it was tapped for geothermal power-generating capabilities years ago, which altered the state of this landscape forever.

For a place usually dismissed for its nothingness, Nevada sure gets to lay claim to all kinds of wild superlatives: the most mountainous, the driest, and also the most seismically active, to name a few among many. Brimming with so many fault lines—or cracks in the earth that allow hot water to circulate in the mighty basins beneath—there are so many hot pots and fumaroles out there in Nevada wild that the pros say that even if you put the most geothermally active places in the world inside the Great Basin’s topography—so that would include Western Turkey, the north island of New Zealand, and all of Iceland—Nevada’s colossal terrain would still have acreage to spare.

Point is, it’s not just that there is a super-strong geothermal and seismic relationship here in the Sagebrush State, but that the acreage we’re talking about is so enormous, which makes it one of the most geothermally active places in the world. Plus as if steamy pools all across Nevada weren’t enough to make you believe Nevada’s one of the planet’s most obvious geothermally active places, seismic students estimate that around 40 to 75% of the Great Basin’s geothermal systems are hidden deep beneath the ground. It’s vast, complicated, and a lot of hot water with even more ideas of how to best reap its distinctive benefits we’re talking about here.

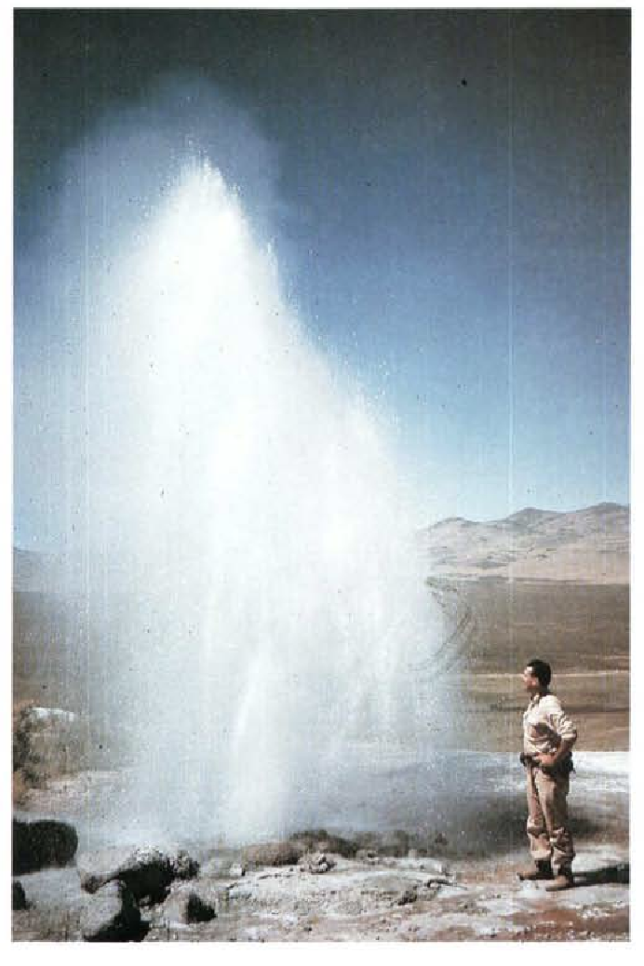

But, back to Steamboat and the 70 foot-tall geyser that once catapulted out of the ground. The Washoe, Northern Paiute, and Western Shoshone people moved throughout Nevada’s massive basins with the changing seasons, and revered Nevada hot springs as sacred ground, Steamboat Hot Springs included. Then, with the calamitous arrival of Euro-Americans and the national wideswept trend of turning natural hot springs into luxury bathhouse experiences, Steamboat would become a tourist attraction permanently.

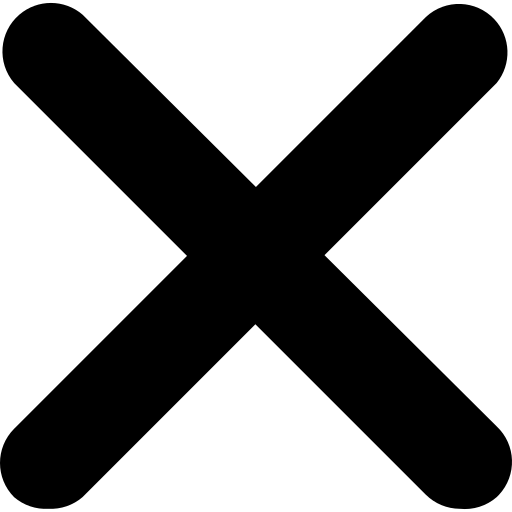

Steamboat showcased one prominent geyser, but also featured about 20 smaller ones, forming one of the largest geyser fields in the entire freakin’ world. Early pioneer journals noted an astonishing 60 to 70 columns of steam could be seen back then, and honestly I can’t even imagine what that experience must’ve been like. One I wish I could time travel to have seen with my own eyes. It became a stagecoach stop, and then turned into a wellness center, hotel, and Comstock millionaire or not, became a place to stop and marvel at that 70-foot-tall geyser. Imagine seeing that gushing at full bore.

An earthquake in 1900 shook up the flow of hot springs and disrupted the geyser, which hasn’t spouted in the years since. Then Ormat, one of the world’s leading geothermal plant producers, tapped into Steamboat in 1992 and well, I don’t think the geyser is coming back. Timothy O’Sullivan, who one of the West’s most famous documenters, photographed Steamboat Hot Springs’ famous fumaroles (or natural cracks in the ground where steam visibly escapes), though not much historic visual evidence exists of what Steamboat geyser once looked like, at least from what I could find. But, it’s far from the only geyser in the Nevada history books.

Fly Geyser & the sacred pyramid lake steam geyser

Fly Geyser, the one that National Geographic made famous on its cover and one the Burning Man Project charges you $40 bucks to look at, is probably Nevada’s most famous geyser, at least at this particular intersection of time.

Plenty of hot water and other geothermally active energies lure backroaders and desert dreamers alike up to the Black Rock Desert all twelve months of the year, and that rainbow-colored man made geyser surely plays a big part in it all.

But unlike Steamboat and the other geysers in this Legend of Lost Nevada, Fly Geyser was man made, drilled by early homesteading pioneers searching for a dependable source of water in the driest state in America, and later reconsidered for you guessed it—geothermal power producing capabilities. Also unlike the rest in this tale, Fly Geyser is covered in thermophilic algae, which is what gives it its wild ass vibrancy, beholding just about every hue on the color spectrum.

Also in this part of the western Great Basin you’ll find the Pyramid Lake geysers at the off-limits Needles, which have been closed due to vandalism since the 1980s. Like all other hot springs in Nevada and far beyond, The Needles and the amazing geyser erupting within was used as a natural place to offer prayer, fostering the same spiritual qualities to the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe as, say, a church. Thankfully, this geyser and any others in the area are a no-go to geothermal developers thanks to the protection of the Tribe.

Chances are this probably wasn’t the only natural geyser at Pyramid Lake throughout the centuries, considering the area is one of the most fantastic displays of the West’s tufa formations, or calcium deposits made by the slow percolation of hot springs. Like the Stone Mother and Pyramid formation itself (also made of tufa), the Needles are totally off limits to non-tribal members (read: trespassers will be ticketed and fined). But, erupting 25 feet beyond the tufa formations at the northwest shoreline of Pyramid Lake, you can still see the steam geyser from a very public Surprise Valley Road, especially during winter months.

Dixie Valley: Nevada’s Geothermal power generating hq

Then there’s probably the most controversial of them all: Dixie Valley. When it comes to using the earth’s heat to make electricity, geologists have been studying Dixie Valley since the 50s after some of the three largest earthquakes ever recorded in Nevada history happened here. All of them were over a 6.0+ magnitude, including Fairview Earthquake (7.3), and the Dixie Valley Earthquake (6.9) whose rumblings were so significant that church bells were said to have rang in places as far away as Missouri. Since those major seismic events, a lot of work has been devoted to studying the nature of faulting across Dixie Valley, which of course involves geothermal systems above and below the ground surface.

But then, then there were the toads. While geothermal power generation has long been happening in Dixie Valley, a plan was approved in late 2021 to take its existing geothermal generating capabilities to the moon with the authorization of two 30-megawatt geothermal power plants and up to 18 production and injection well sites. Even though geothermal power can run 24/7, it’s scalable, its physical footprint is far less than wind or solar, and it’s proven to drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions, geothermal power plants are exceptionally noisy and bright.

The type of light and noise geothermal plants produce may not be a big deal in a city or town, but out in Nevada’s Great Basin—or some of the most lasting dark sky country around and some of the quietest natural soundscapes there are—a plant like this can be devastating to recreationalists and conservationists, but also to the many creatures who’ve long lived here, and in some cases, nowhere else on earth.

One time we went to this Greater Sage-Grouse lecture in Elko and one of the folks presenting was a scientist who’d devoted his life to studying these fascinating creatures. He spoke a lot about how their habitats are disappearing for a lot of reasons, ranging from sagebrush rangeland threats (like wildfire) to interference of man, like geothermal power plants, which are devastatingly bright and noisy, at least compared to other power-generating plants.

Surprisingly enough, he mentioned a specific study conducted in Dixie Valley, where they were able to determine the Dixie Valley geothermal power plant not only pushed the Greater Sage-Grouse out of the valley entirely, but also a lot of other types of wildlife, like pronghorn antelope, coyote, and raptors, to name a few among many. In particular, he said the lights and noise from the Dixie Valley geothermal plant pushed most wildlife at least 15 miles away from it, if not out of the valley entirely.

Once greenlighted to expand their geothermal operations by a lot, the Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Tribe sued the BLM, citing both the threat to the natural hot springs in the valley (some of which were already ruined by their operation, like those up in Jersey Valley), and the Dixie Valley toad, which lives in marshy wetlands created by tiny flow runoff from geothermal activities and nowhere else on earth.

Water in the desert has always been something humans have fought over and as the years go by, will probably continue to be the most sacred thing in the driest environment in the country. And while it’s so completely crucial for humans, what may look like a tiny pool or insignificant wetland not much bigger than a wide spot in the road is an essential habitat to animals and other creatures who rely on them. Because the other option is to be completely extinct.

Meet the Beowawe Geysers: The Second Largest Geyser in North America

Over on the eastern side of the state, second only to Steamboat’s once-visible geyser field, there was Beowawe. And strap in, because the origin story of this place is basically the wildest tale of them all—at least in my hyper-active imagination, it is. This is the type of story I wish I could take the credit for dreaming up myself, but it’s based on actual historical accounts which makes it that much better.

To most people Beowawe is that one kinda-scary rest stop between Battle Mountain and Elko on Nevada’s Interstate 80 that’s somehow always under construction and roped off. At least, that’s all it has been to me before learning the tale of the lost geysers that once fanned high over the valley south of the highway there. But even in a state whose many towns and geographic features’ nomenclature originates from cultures around the world or are made up words altogether, Beowawe definitely manages to stand out.

Legend has it that an enormous man in stature and size, reportedly weighing at least 300 pounds or more, came to this north central stretch of Nevada looking for possible places to set up towns to support the Central Pacific Railroad. His name was J.A. Fillmore, and apparently while looking for future depot stops, he stopped along the banks of the Humboldt River to relieve himself when a Paiute woman saw him. Naturally, she was absolutely terrified at what I’m guessing was the largest white man she’d ever seen in general but especially at the sight of him going number two, and ran off, screaming Bea-wa-we, which loosely translates to “big butt” in Paiute.

But it doesn’t stop there. Then there are equally thrilling explanations for the origin of this word by modern tribesmen. Paiutes also claim part of the word, Bewa, translates to “big balls” (also totally possible based on what this lady probably saw before her), while the Shoshone say Bewa means “the runs” or simply “place to take a dump” and argue that the word could even be interpreted as “big wagon”. So whether this large, large man had dumps like a truck (or wagon), got the runs, had astounding anatomy, or maybe even all three, this actually happened.

Once Fillmore pulled it together and stopped terrorizing the original inhabitants of what would forever be known from that moment forward as Beowawe, this shallow, gravely spot along the Humboldt River became the safest place for California-bound conestogas to cross Nevada’s longest river system. It was also a place the Paiute and other tribal nations had used for decades. Even though it first started off as a shipping point to the mines in the area, the arrival of the Transcontinental Railroad prompted the formation of the town of Beowawe, which eventually reached its peak in 1881 with 60-ish people living here. Like everywhere else in Nevada, fire would eventually destroy it.

It’s important to note that lots and lots of conflict happened here. With an unending stream of wagons passing through and also setting up camp in this shallow gravely spot along the Humboldt, the location basically became a pioneer landmark: Gravelly Ford. Of course having already been used for easy access to the river from the region’s original land owners, this of course made tensions between Nevada’s indigenous population and westward pioneers soar.

A long, long list of massacres happened at Beowawe, and while there is a pioneer cemetery nearby monumentalizing the “Maiden’s Grave” and other families who wouldn’t survive the trek West, there are easily twice as many natives who lost their lives here who don’t have a well-kept historic cemetery to stop and see.

The Geysers of Whirlwind Valley

Besides a shallow, safe place to cross the Humboldt River along the California Trail, Gravelly Ford also of course promised reliable access to water, and plenty of hot springs throughout Crescent Valley where pioneers could stop, rest, and maybe even have a bath. And what a freakin’ bath that must’ve been, considering there was a 215 foot-tall hot geyser that once blasted out of the earth here. That, and together with twenty seven more geysers ranging from one-to-88 feet tall, the Beowawe Geysers formed the second most significant geyser field in the entire continent.

To put it all in perspective, Yellowstone’s Steamboat Geyser—the largest natural geyser in North America and the entire world—erupts to 300 feet tall, and Old Faithful usually ranges from 106 to 180 feet each time she blows. So Beowawe’s main geyser erupting 215 feet over the Great Basin Desert made it not only twice the size of Reno’s Steamboat Hot Springs, but made it taller than Old Faithful and just 75 feet shy of one of the tallest, most powerful geysers in the whole world.

Despite all this pioneer traffic and plenty of violence happening mere miles from the Beowawe Geysers for many years, this incredible geothermal site southwest of Beowawe in a place called Whirlwind Valley (!!) was mentioned in a few Central Pacific Railroad sightseeing guides, though nobody really paid much attention to them until 1934 when its geologic accounts were actually documented for real. USGS geologists noted many hot springs on the surface and many fumaroles, but most importantly (at least geologically speaking) was Beowawe’s old sinter terrace, which if you’ve been to places like Diana’s Punchbowl, is exactly like that: terraces or mounds of layered rock surface made from super-fine silica that points to past geothermal activity.

And then from 1945 to 1957, many USGS expeditions were made to the Beowawe Geysers, whose reports ultimately attracted the attention of my forever hero, Nell Murbarger, who wrote about them in the January 1956 edition of Desert Magazine. In her article, Geysers of Whirlwind Valley, Murbarger challenges her reader (at least this future reader) by reporting she discovered that this “remote pocket in the mountains of north central Nevada with a colorful terrace and boiling pools provide an amazing spectacle for the few people who venture over the treacherous road that leads to this spot.” She goes on to say that she heard about Beowawe from a Basque sheepherder who told her about the site in a garbled mixture of French, Spanish, and English, and over a dying campfire under a stormy sky in the Toiyabe Mountains. Damn. She and I would’ve definitely been friends.

Having roamed just about every mountain and valley in the Sagebrush State, she doubted him (or maybe herself for not understanding him), wondering how such a place could’ve escaped her knowledge. But, she was able to confirm his jumbled proclamation by the Mackay School of Mines in Reno, and later, more rural Nevadans she met along the way. My gal. In her article she notes that she arrived at night and camped next to the hot spring, astonished at sunrise by just how enormous the site was.

While she initially estimated a ledge to be 10 to 12 feet wide, once the sun rose, it actually turned out to be one hundred, with “every square foot of the area alive with thermal activity”. That, and what she first believed to be dead fumaroles were alive with 30 foot-wide columns of water, boiling springs of every size, and a dark blow-hole of unknown depths. She spent the rest of her time here marveling at the geothermal activity, squeezing in a long mineral bath, and searching for “Indian relics”, noting “for in my belief lies my assurance that Whirlwind Valley will still be unchanged when next I have an opportunity to visit it.” Oh Nell, how I really wish that were still actually true.

It took her three attempts to reach the Beowawe Geysers, which had remained unexploited during her 1956 visit, and very much unlike my stop by in 2024. Knowing very well that all kinds of geothermal power companies had gotten their hooks in this site just three years after Nell’s 1959 voyage, I still wanted to see it, hoping maybe there was some sign of an old geyser, or perhaps even a less significant power generating pool somewhere around there. So in April 2024 after heading to Elko County to survey Greater Sage Grouse Leks at the Cottonwood Ranch, we pointed the tires south of Interstate 80 in search of any sign of the continent’s second largest geyser.

Instead and to our prediction, we were met with a giant geothermal power plant tank farm, with no signs of any geysers, now only a legend. Sure, there was plenty of water in that valley, alkali too, but no geyser. No soakable spots, either. Even though power harnessing operations have been involved here for many decades, Beowawe Power LLC signed a 29 year contract with NV Energy in 2006 tapping the 208 degree fahrenheit Beowawe hot springs right at the source. Goodbye geyser, sayonara hot spring.

While we won’t ever be able to see Nevada’s land of lost geyser fields with our own eyes, at least not the 200-footers like Murbarger once saw, I have a lot of contentment with wondering about if we may have stepped in the same spot, noticed how the light hit that particular spot on the mountain way down there, taken in that exact view of the Great Basin’s colossal expanse, or even set up our camp in the same place for the night, Nell and I.

The good news is there are still a few bubbling up out there in Nevada wild that I would absolutely, and with enthusiasm, challenge you to go find. The ones that you can’t see right away, but are definitely and without question there. And whether it’s Nell’s legacy we’re keeping upright or that of our very own, the quest of Finding Nevada Wild won’t ever disappear.

Sources:

- “Beowawe, Nevada”, Wikipedia, April 2, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beowawe,_Nevada

- “Fly Geyser”, Wikipedia, January 20, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fly_Geyser

- “In the U.S., Steamboat Hot Springs, Nevada”, National Park Service/U.S. Department of the Interior, April 2024, https://www.nps.gov/features/yell/ofvec/exhibits/treasures/global/steamboat.htm

- McKenzie, Jessica, “Showdown in Dixie Valley”, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, November 7, 2022, Wikipedia/11/geothermal-energy-dixie-valley-toad-biodiversity/

- Murbarger, Nell, “Geysers of Whirlwind Valley” Desert Magazine, January 1956, Vol. 18, Issue 1, https://archive.org/details/sim_desert_1956-01_19_1/page/n19/mode/2up

- Newton, Marilyn, “Beowawe: Nevada’s town name may have salacious origins”, Reno Gazette-Journal, February 15, 2014, https://www.rgj.com/story/life/2014/02/13/beowawe/5467081/

- “Site Description: Beowawe”, Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, 2014, https://data.nbmg.unr.edu/Public/Geothermal/SiteDescriptions/Beowawe.pdf

- “Steamboat Springs (Nevada)”, Wikipedia, January 29, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steamboat_Springs_(Nevada)

- “The Needles at Pyramid Lake”, All Around Nevada: Explore the Silver State (and beyond) in Virtual Reality, April 2024, https://allaroundnevada.com/needles/

- White, Donald E., “The Beowawe Geysers, Nevada, Before Geothermal Development”, U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1998, https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/1998/report.pdf