Prefer to Hear this Story Instead? Listen Here.

There aren’t many places in Nevada that behold something I really can’t explain—Jarbidge is one of them, and my strange stories aren’t the only ones to originate from these woods.

Part 1: Jarbidge Wilderness and the Lost Sheepherder’s Mine

Perched in Nevada’s upper right hand corner where Nevada meets Idaho, folklore here runs just about as deep as its thousand foot river canyons the way it always has since man first set foot here an astonishing 14,000 years ago. The Shoshone, who moved with the seasons throughout most of modern-day Nevada and were the first to live in this region of the Western United States, were the first people to live around the present Jarbidge River canyon and Jarbidge Wilderness Area—double underscore on the around.

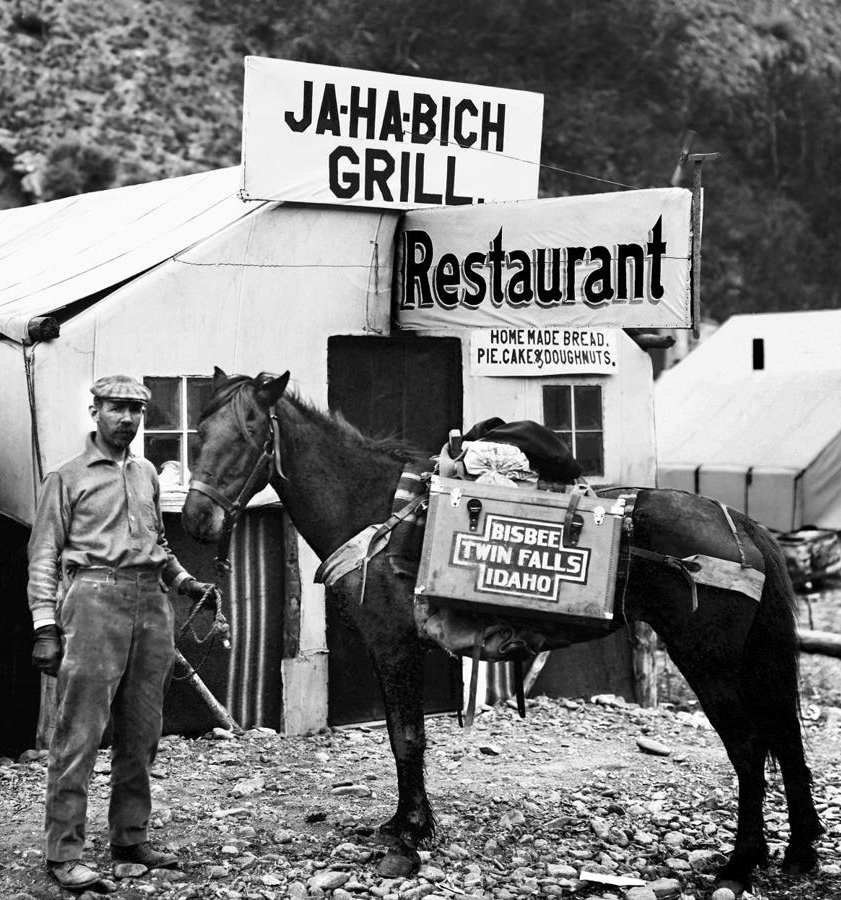

So what does Jarbidge mean, anyway? Like a lot of towns in Nevada it’s a made up word, a bastardization of the Shoshone word T’Sawhawbitts (pronounced like Tuh-Suh-Haw-Bits.) Through the years, as pioneers, miners, and other Westward explorers arrived in the region, it evolved from its original T’Sawhawbitts, to Jahabich, to Jarbidge—but rest assured, no matter what 6th generation Nevadans and Elko County residents may insist upon, it’s never been JarbRidge, just Jarbidge.

But back to its original name—ever wonder what that word actually means? In Shoshone, T’Sawhawbitts simply translates to Devil. Even though the Shoshone lived around the Jarbidge River canyon, they wouldn’t enter it regularly or dare live inside because they believed a dangerous beastly creature lived within, haunting this rugged mountainous terrain.

I can tell you by personal experience that a string of bad luck continues to happen to us here each and every summer where, even for a pair of experienced Nevada explorers, hits me in a chaotic and unpredictable way. It’s the only time in Nevada where we’ve ever been spooked at night, when we heard old-timey music in the middle of nowhere with no possible campers around us on more than one occasion. On the most basic level, I can’t explain it.

Neither can all the old timers in Jarbidge, who’re still talking about a headless skeleton that guards an undiscovered gold claim in the Jarbidge River Canyon. Jarbidge was one of the last great gold rushes in the American West with a bonanza at the turn of the 20th century. But before that, with gold and silver beckoning people east from California and into Nevada, prospectors, homesteaders, and every Euro-explorer in between first arrived to the Jarbidge area in the 1870s. Legend has it that a man named Ross was investigating gold float—or particles of gold so small they can be seen floating down rivers and streams—in the Jarbidge River. Knowing there was surely gold awaiting discovery deep in the canyon’s walls, his search persisted for many seasons where he would walk the Jarbidge Wilderness mountain sides in the spring, summer, and early fall before being shut out of the canyon by wintry weather.

Finally, Ross discovered the gold bounties he dreamt of, and right on the brink of winter. Leaving his tools right where he cried eureka, he told only one other person about the location of his discovery—a sheepherder named Russ Ishman who also knew this countryside from years tending to his flock. Legend has it that Ross told Russ (not the greatest pair of names, I know) he would work his claim in the spring but if he somehow didn’t return, Russ should consider the caché his property and develop it himself.

Well, the next spring arrived and Russ returned to his flock in Jarbidge, yet Ross was nowhere to be found. Knowing the region Ross described, Russ spent the entire summer searching for the fabled ledge, locating it right as winter arrived yet again. Here, he discovered all of Ross’ tools right as he’d left them, along with a complete skeleton positioned nearby. Was it Ross’? We don’t know. In the most sinister of ways, Russ took the head, climbed out of the canyon and recounted the tale to his boss, John Pence, where they immediately planned to relocate the site in the spring and uncover their reward.

So, by the time warmer weather rolled around again, the pair began ascending the Jarbidge Mountains—some of the tallest, and definitely some of the most ruggedly remote in the state—to the fabled gold-laden ledge. And even though Russ had worked this terrain for many years, the the trek was too steep, too fast. Russ died on the ascent from a brain hemorrhage, and even though he too had explained the location to his employer ahead of their voyage, the ledge has never been located.

SAGE SECRET: This whole situation—where a high desert prospector or adventurer spoke of the next big mineral caché on their death bed, but could never quite get the exact coordinates out before kicking the can—has happened many times in Nevada history, by the way. Snowshoe Thompson is another example, where he spoke of the next bonanza somewhere down in Diamond Valley. Nobody could ever quite locate that fabled deposit, either.

Fast forward 30 years to 1908 when high grade gold ore was discovered near the Jarbidge River, which some believed was finally the discovery of the legendary Lost Sheepherders’ Mine, but was quickly disproved with differing mineral purities. Legend has it that this gold laden ledge still awaits discovery somewhere in the Jarbidge Wilderness, at least enough to inspire a few modern day gold mining companies to set up in downtown Jarbidge once more to explore the region’s mineral prospects. This is a controversy of course among locals, who weren’t exactly thrilled to see a modern man camp set up in their population: 19 town. And despite man camp employees hoping the locals may slip up after a few too many cold ones at the Outdoor Inn revealing details about Deer Creek Cave, God’s Pocket, and maybe even the Lost Sheepherder’s Ledge, nobody has yet to discover it.

Editor’s Note

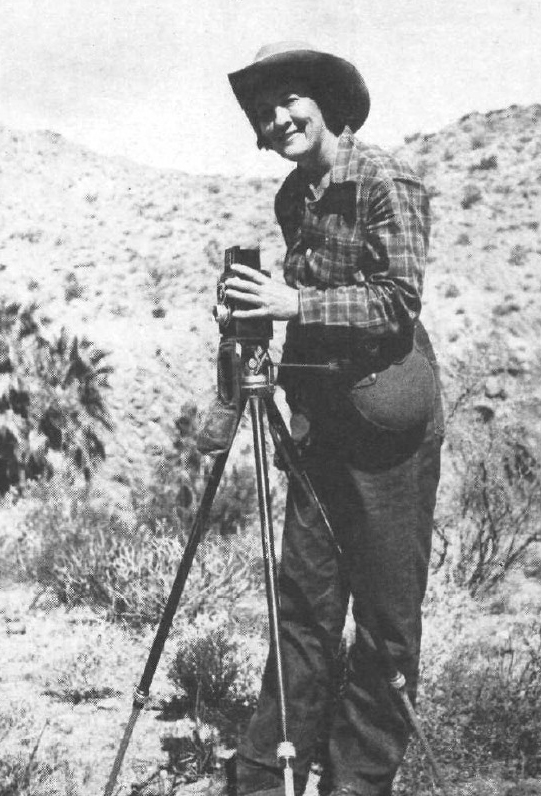

There’s no way I would’ve ever discovered this story if it weren’t for my hero, Nell Murbarger.

The original desert rambler of Nevada, Nell’s work for Desert Life Magazine brought her into The Great Basin, where she traveled solo in her station wagon during the 1940s-50s to cover Nevada’s freshly abandoned ghost towns and meet with many people who were still alive, and worked them just a few years prior.

I have an unending interest in Nevada, but Nell’s work has made it stretch even further.

Read more about her coverage of the Lost Sheepherder’s Mine in Sovereigns of the Sage, and if you haven’t picked up Ghosts of the Glory Trail, I really urge that you do.