Cal-said-oh-ney. It’s the type of geologic discovery that will take over your life if you’re not careful.

Truth be told, rootin’ around in the dirt, and for hours on end, is not exactly the type of hobby I imagined being wrapped up in. Then again, that’s the very way Nevada enchants, calling you deeper and deeper into the desert for one thing or another, and in this case, it’s the allure in the unknown of every unturned stone.

With some of the most unusual geology in the West, country, and entire world, Nevada’s is a geologist’s wet dream. From ancient prehistoric swamps, to sunken opalized forests, to more turquoise mines than anywhere else, there’s a lot worth digging into out there. And a lot like hot springs or forgotten summit trails to skyscraping peaks, Nevada rockhounding is easy to become consumed by, with free public lands dig sites every-freakin-where. Even then, the cardinal rule with Nevada dirt-road-ramblin’ is knowing whose land you’re on. It’s easy to start assuming everything out there is yours because most of the time it is—except for when it’s not.

Most of the time the most carat-producing rockhounding sites in Nevada are either private claims with a pay-to-dig operation going on (think Otteson’s turquoise mine, or even the Black Fire Opal mines up in the Sheldon), or lie within very clearly marked BLM lands (like Garnet Hill). But every now and then you’ll come across a place that still feels wild because, private or public, or in this case both, it is. I’d been hearing stories about blue lace agate too good to be true and finally figured out exactly where in the Sagebrush Kingdom it was located. Squarely on private land. Glad I checked—because nobody wants to be that guy. Sometimes Nevada’s one degree of separation works against you, and other times it all plays to your advantage. As for this particular instance, I was able to get in touch with the claim owner and ask permission to make a visit. And baby—ask and you shall receive.

My husband and I have traveled to Nevada’s deepest darkest corners to root around in the dirt, and for hours on end, but for this particular trip, my Dad and I jumped in the car and pointed the tires east along Nevada’s Highway 50—a route proclaimed as the loneliest, but something I’ve always strongly felt is anything but. Ever since I can remember, my Dad and I have picked up rocks from all over the country and gifted them to each other—speaking of which, did you know if you find a rock with a stripe in it, it’s good luck? Geology nerds like me refer to them as Wishing Stones, and in my family, we like to believe that they’re even more powerfully lucky when you give them to someone else. Anyway, we’ve picked up unusual rocks from all over the country and gifted them to each other through the years, so you could say rocks and rockhounding has been our thing.

First thing on the agenda? Middlegate Station, of course. Situated about an hour east of Fallon along Nevada’s Highway 50, not much else is out there, making it easy to locate and drive right on into that gravel driveway. Said to be the last true roadhouse in America (or something like that, anyway), Middlegate Station is found in it’s own basin, in between what early pioneers decided was an eastern mountain range with an opening (east gate), and of course a western one as well (west gate), meaning what lies in the middle of it is of course, the one and only Middlegate.

All kinds of pioneer activity occurred across Nevada’s Great Basin beginning in the 1850s and of course many years after, and by the end of the decade, nearly 30 official Pony Express Stations were established across what would become the Silver State, including Middlegate Station—a stage stop where riders could change horses, refuel, and rest up. Despite being one of the most legendary programs the US Government ever instituted, the Pony Express was short-lived, with all stations from Missouri to California abandoned less than 18 months after they were built. Once Middlegate was closed and government-appointed watchmen moved on, area ranchers carried of pieces of Middlegate Station, using its building materials in an otherwise barren (treeless) high desert terrain. Luckily enough, another famous route was punched through by 1916, and ran pretty closely to the original route Pony Express Riders navigated just 57 years before.

Something like a trip out to Austin and back may seem like a commitment to most people, but feels like a blink of an eye for me and my husband, who’ve logged thousands upon thousands of hours along Nevada’s rural highways. There was a time I joked that I had driven Highway 50 at least 50 times in one year, but I’m positive I actually did. Nevada is the most mountainous place in the country, with more than 300 ranges stretching north-south. When you travel a road like Nevada’s Highway 50, you sure can feel it, as you climb up and over a high elevation mountain pass, drop down into iconic basin and range topography, and repeat—over and over. The drive from Reno to Austin along Highway 50 is no different, with some of Nevada’s most breathtaking scenery—ranging from Dixie Valley’s unmistakable alkali flats, to the longest mountain range in Nevada, and beyond—valley after valley.

It felt like a blink of an eye before we were in Austin—Nevada’s “City of Churches.” Another one of Nevada’s most famous 19th-century silver mining districts, Austin, NV is nestled in the northern end of the Toiyabe Mountains—one of the longest, and most mysterious mountain ranges in all of Nevada. Less than 200 people call Austin home today, and boy, you can really feel it as you throw it in park and take a stroll through the mostly-abandoned town before you.

At one point Austin teemed with a grocery store and lumber yard, multiple restaurants and gas stations, several different turquoise shops, and in true Nevada fashion, many saloons, but not much remains open there today. While a few motel options have stayed open, there’s really only one place to eat in Austin, one gas station, and the most glorious turquoise shop in all of Nevada. But, that could all change soon, at least I sure hope so. Story has it that a professional gambler from Las Vegas has been purchasing up most vacant properties throughout town, and I have to hope that he’s got plans to someday reopen it all—at least that would sure be one hell of a Nevada story, wouldn’t it?

My Dad and I refuelled, threw it in park, took a walk around town, and beelined it straight for the best turquoise shop in all of Nevada: Jason’s Art Gallery. Manned by owners Duane and Jeanne (and named after their son, Jason), most of what you’ll find within tiny Nevada turquoise store is all mined from their Little Bluebird turquoise mine, cut, polished, and set by Duane, and sold to you by Jeanne herself. One of my favorite things about turquoise is that there are so damn many varieties, and that everyone seems to love something a little different. The good news is, Jason’s Art Gallery offers just that, with classic deep Royston blues, to light robin’s egg varieties, to wild horse, white buffalo, and beyond. And best yet, offering necklaces, money clips, bracelets, rings, hat pins, and more, Duane’s probably made whatever it is you’re looking for, and offers everything at the most affordable rates I’ve ever found.

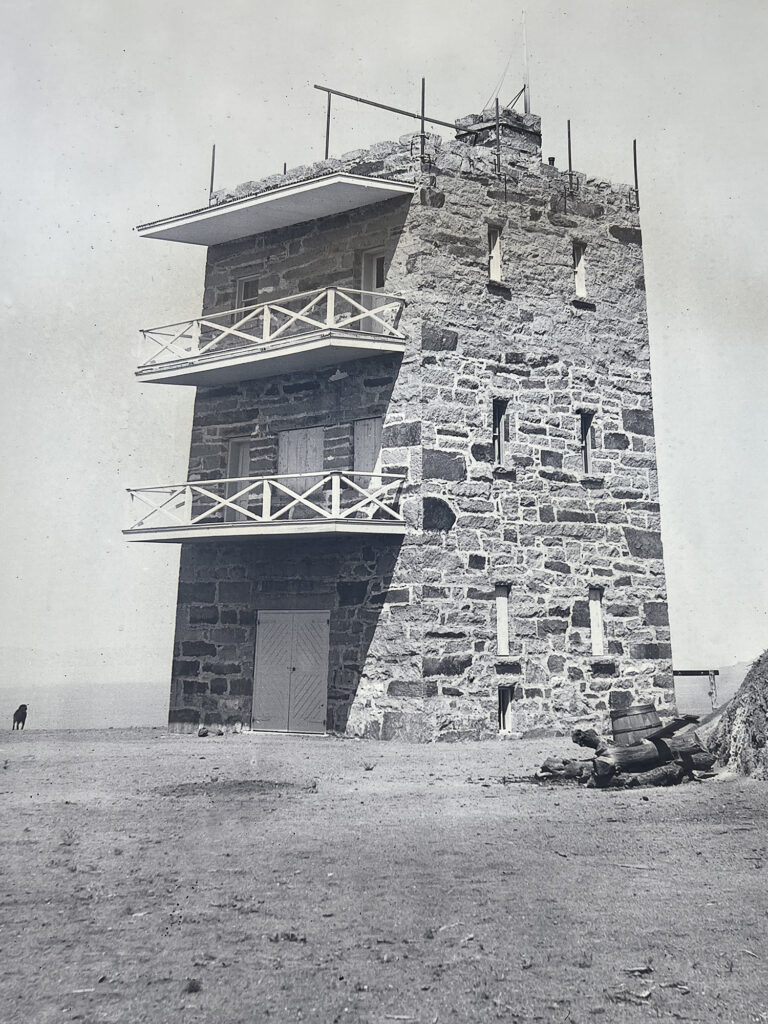

Back in the car, I realized my Dad had never been up to Stokes Castle, so we pointed the tires up behind Champ’s Gas Station to a piece of Anson Phelps Stokes’ American Dream. A businessmen who brought his family to Austin during its peak years, Stokes built the home in 1897 as a summer retreat, modeling it after structures he’d seen in Italy. This three-story, native granite-made mansion was complete right as Austin’s silver caches were waning, and if you can believe it, Anson and his family spent only one month living in the castle. The main floor contained a kitchen, while the second and third offered bedrooms and balconies. Each floor had a fireplace, and the roof terrace offered a sun deck with 100-mile views of the Reese River Valley below.

By 1898, Anson sold his Austin mine, all the milling equipment to go along with it, and the castle, never to return to central Nevada again. Once one of the most lavish structures in all of the Austin mining district, the brand-new castle sat completely abandoned until the 1950s when one of Anson’s cousins purchased the castle.

Today, the Austin Historical Society maintains the property—meaning they put up a chain link fence to thwart vandals many years ago. Other than that, not much visible restoration is in play, with the balconies long gone, once-boarded now-exposed windows and doors, and those massive chunks of granite slowly tumbling down. There’s a spot in the fence wide enough to squeeze a camera (and body) through if you want to go in to take a few pictures, even though I joke this is how I’ll probably go out some day—a giant brick eroding off the top of an abandoned structure bonking my head into my grave. Even though no much historic integrity remains, that 100-mile vantage point from Stokes’ Castle is still fully available, offering some of the best perspectives of classic Basin & Range landscapes in Nevada borders.

Now onto another castle, and just down the road—the Paradise Ranch Castle, a true Nevada oddity that, bonus, begs a stay if you’re up for a bit of an odd night. Owned by proprietor Donna and her late husband Bob, Donna and her new companion David run this concrete castle in the desert, welcoming guests from all over the state, West, and world to the deliciously remote Reese River Valley. Once I stayed there with some folks from Germany and France, who’d flown into New York, driven across the United States to experience some of the country’s most famous landmarks and attractions, and were on their way to San Francisco when they decided to stop for a stay at the Paradise Ranch Castle. I thought to myself, “These are probably people who’ve experienced many real castles—how in the hell did they end up at this odd American version of one?? “But that’s the way the real Nevada operates, offering genuine experiences you can’t understand from the guidebooks, but can only see once you’re out there, in it.

Let me just say this: Bob was a prolific collector. All of his collections are on full display throughout the castle, including a wide array of all kinds of unusual musical instruments, a pretty valuable range of Cleveland Indians memorabilia (their home state), swords, dolls, entire suits of armor, and mannequins dressed head-to-toe in medieval garb. It’s wild. Donna welcomes guests into a few different sleeping arrangements upstairs, along with one escape-room-style accommodation in the basement that even she admitted people are way too afraid to actually stay in, and “The Dungeon”—a game room and bar filled with a jukebox, pool table, aquariums, and leather couches to stretch out on. It’s a weird place—fun, but really weird.

My Dad and I settled in, then got to work on locating the bounty we were seeking: that blue chalcedony. Donna and David knew all about it, the rockhound’s paradise that surrounded their property, warned us about a myriad of private claims, pointed off in the distance in the right direction, and without about an hour-or-so of remaining daylight, we headed into the hills. Timing our drip during late July, it was peak summer, which lent that special glow only Western skies can produce, and late into the evening. As with any rockhounding, especially in a place like Nevada where it isn’t all too obvious, the best way to start is to begin.

Taking side roads that led to routes almost reclaimed by the desert altogether we climbed higher in elevation into the rolling sagebrush steppe. With not one soul around, any “dig sites” were far from obvious. So on a big ol’ beautiful vista, we pulled over the car, unloaded our rockhounding tools, and started swingin’ a pickaxe into any and everything. And just like that, periwinkle blues ribboned through every unturned stone. Depending on what it is you’re looking for, rockhounding is certainly the type of hobby that solicits equal parts patience and grit—you have to root around for a while before you’re likely to find something worth keeping, and you’re probably going to get dirty along the way. And as I dug further into the mountainside, this perfect July evening was no exception. I quickly filled my bucket, amazed and the trove of blue chalcedony and blue lace agate I was discovering with not much effort.

While my Dad was starting to get the hang of things closer to the vehicle, I settled down along a bank and started digging away at the wall, hoping to uncover something good—like really good. Nearly 8:30 PM now I stopped to look out over Reese River Valley, now lit up with the type of fiery skies that only seem to happen to this extent in the central part of the state. With the Toiyabe Mountains and Bunker Hill in the distance, everything in the world was perfect. The rich aroma of sage hung in the area, and a pastel panorama offered beautiful sights in every direction, trying to take a long enough look for it to stick with me forever. Horny toads, jackrabbits, and dozens of pronghorn antelope began to emerge out into the warm desert night, and I turned back to the bank, dragging the rock hammer’s tip along the wall, loosening sediment that had probably been there for eons, but felt freshly deposited by the most recent rain.

Fistfulls of blue chalcedony jostled loose and into my bucket, each one seemingly better than the last, until my rock hammer snagged on something. Assuming it was just a rock or even a sagebrush root, I unfurled its grip, noticing the corner of the rock it was indeed hung up on was the pale blue hue that called me out here to begin with. Slowly nestling the tip along a safe, unbreakable edge I pried that sucker free, stunned with my baseball-sized beautiful botryoidal discovery—heart of the damn desert.

I excitedly called my Dad over, holding onto one of those magic moments that can only happen when you’re out there in it, who arrived with a spray bottle in hand, ready to wash off my fist-sized chunk of a rock. Blue chalcedony is spectacular alkali-powdered and pried straight from the earth, but once its gleaming, mysterious cornflower blues come alive with a little spritz of water? Definitely something you’d never expect to spring free from dusty ol’ Nevada. Land of a thousand thrills is right.