Prefer to Hear this story Instead? Listen Here.

To live life in a secret hideaway locked deep inside a faraway Nevada canyon. It’s the ultimate dream, at least for me, but it was also one of what’s said to have been an almost-mythical desert frontiersmen, Jack Longstreet.

I spend a lot of my time tracking down not only Nevada’s most isolated places, but the feeling of isolation. The type of places that have just about been swallowed up by the desert altogether, and are only really noticed as you’re scouring the atlas bumping down an old gravel road, or from following old bullet-hole riddled signs that point right to them from the main highway.

They’re the spots where you’re almost guaranteed to not cross paths with a single soul throughout the duration of your two-day ramble and the type of hideout where you can let your mind wander just as far off as you are from the nearest highway. Where you can quiet your mind in the closest thing to true silence you’ve probably ever listened for, and wonder what’s at the end of that canyon road over there, then actually follow it find out. To feel real connection with your co-pilot, and with the Sagebrush Ocean that surrounds the two of you.

Even though Jack Longstreet lived in another era with an entirely different set of circumstances, this is basically the way Jack Longstreet decided to live his life, and over and over again, naturally gravitating to hideouts beyond the realm of law and to places where people didn’t know him, or his past. Yet, despite being a rugged individualist with a strong moral code, wherever he roamed, trouble usually followed, and he saw the ease of avoiding his enemies by living in out-of-the-way places within an “unexplored desert.”

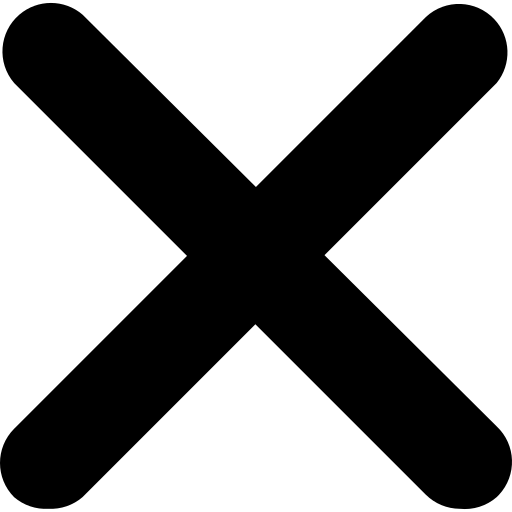

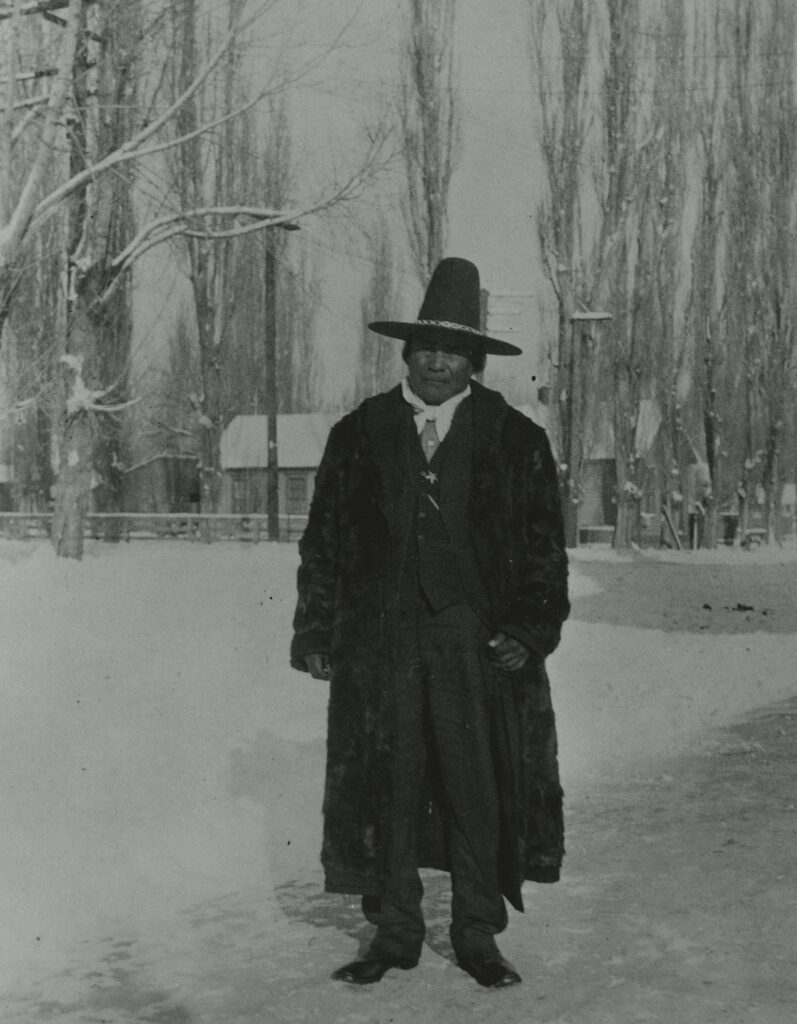

With a missing ear taken from his horse thieving days, notches carved into his long barrel .44 Colt, and a broad, muscular build, people feared Longstreet but the truth is he was just about as misunderstood as the Great Basin itself, epitomizing the mythical Western frontiersmen with self-reliance, independence, and fair-mindedness. Jack Longstreet spent almost a full century as an outlaw, Pony Express rider, prospector, rancher, saloon keeper, trailblazer, stagecoach shotgun rider, and fierce defender of Indian rights. Yet, with so much said about him and so little actually known, there’s plenty of room for legend and lore when it comes to the life of Jack Longstreet, and Nevada’s place in it.

A Young (And Wily) jack Longstreet

Believed to have been born in 1834 though nobody really knows for certain, not a whole lot is known about Andrew Jackson Longstreet in his early life, at least before his knack for gun slinging and whiskey drinking earned him a permanent spot on a roster of horse thieves. Or was it stealing cattle? Well, he wrangled and stole some kind of ungulates, he and his crew were all eventually caught, and he was the only one who lived to see another day. This probably all happened in Louisiana by the way, but nobody knows for sure on that, either. Only an early teen and the very youngest member of his gang, the rest were hanged while he got out alive by sparing only an ear, which was the sort of thing that would permanently brand him as an outlaw for the rest of his life.

From that point on, he (understandably so) grew out his light blonde hair in an attempt to cover his ear, and tried to avoid most people where the subject of his missing ear might come up. Then again, if I too were part of the first generation of Western explorers in a truly lawless West, I suppose if someone chopped my ear off I’d probably do the same, along with turning to places of isolation only an unmapped Nevada could produce. But we’re not quite there yet, because this domain in part of what would become the Silver State was still very much Arizona Territory.

Finding El Dorado, And a Tent Saloon in Moapa Valley

Twenty three. That’s how many years young Longstreet was by the time he and his lone ear rode north to El Dorado Canyon, lured by tales of gold to the famous Techatticup Mine at Nelson Ghost Town. Originally reigned by the Spanish and later part of Arizona Territory, a major gold discovery happened here in 1861. If you can imagine the most Wild West cast of misfits, that’s exactly who showed up here, plus what’s said to be plenty of Civil War deserters, and even more renegades, outlaws, and drifters.

In other words, a desert desperado like Longstreet blended in just fine in a gold boomtown chock full of people on the lam from one thing or another, and he got by running a small store in a tent saloon setup near one of Nelson’s main mines. Having spent his teen years perfecting his gun handling skills and even rumored to have ridden as a Pony Express Rider, this is really when he first became friends with the Southern Paiute—maybe because he was also rumored but never confirmed to be half Apache and felt a natural connectedness to them, but also entirely likely because of his affinity of sharing cactus wine and gambling habits alongside them.

Legend has it that Longstreet was more interested in seeing what was at the bottom of his whiskey bottle than he was claimstaking, which is partly why he didn’t hang around Nelson for too long. And while he missed out on thousands in gold bullion claims along the banks of the mighty Colorado, a restlessness inside told him there was lots more eldorado to be discovered in this part of an uncharted West. So he loaded up his tent saloon on his thoroughbred horse (the only thing he was ever said to spend money on, by the way), and sauntered 90 miles north to the next spot he would stake his tent saloon: St. Thomas.

Today we know this place as a waterlogged Nevada ghost town that very recently revealed itself from Lake Mead National Recreation Area’s rapidly receding shoreline. But back before Hoover Dam was constructed and they dammed the Colorado River into the nation’s largest man-made lake, there was St. Thomas. A whole unflooded town that operated exactly the same as any other Nevada-Arizona Territory hopeful, just with lots more Mormons on an undying mission to colonize this part of the West.

While the Mormon-outlaw-style 60ish-person-population that settled in Moapa Valley built homes, plowed the land, dug canals, built roads, planted trees, and formed the towns of St. Joseph, Overton, and St. Thomas, a good deal of these folks were far from upstanding individuals. Matter of fact, so many bad guys had settled into Lincoln County that the Pioche Record suggested calling this part of the world “murderer’s paradise” because so many eluded the law by slipping back and forth across the territorial boundary line.

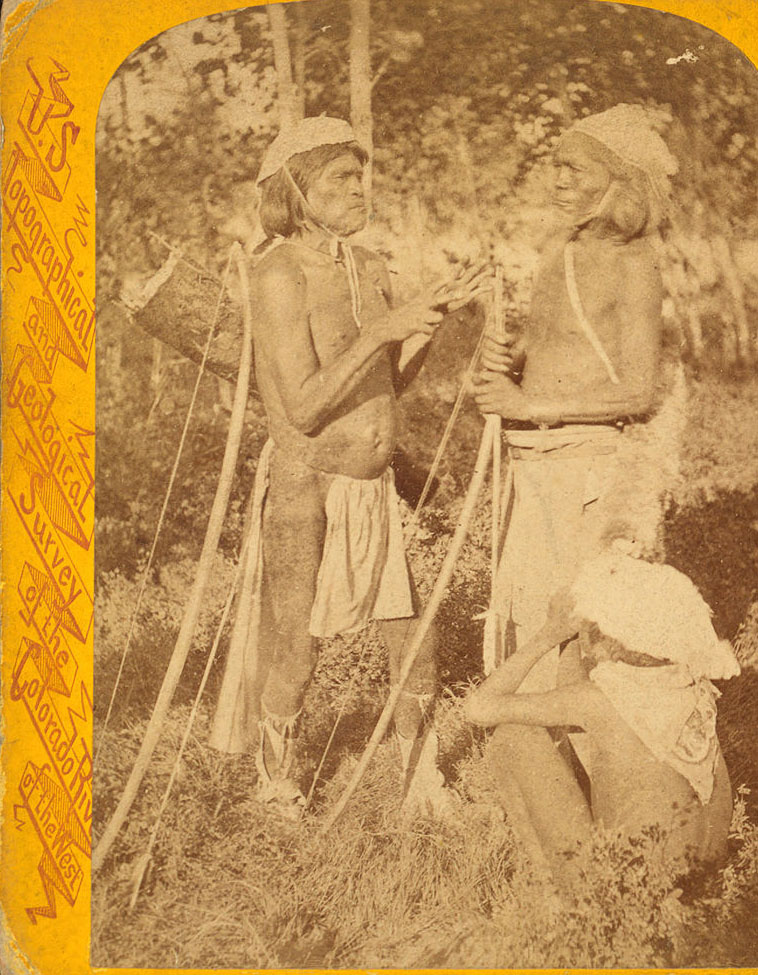

A Legendary Advocate For the Rights of Indian Wrongs

There wasn’t a whole lot of law and order to begin with during this particular time and place, which complicates an already difficult-to-understand situation surrounding the Moapa Valley’s indigenous population. You see, as one of Nevada’s four major tribes, the Southern Paiute had lived in this region for thousands of years prior to the Spanish, and Euro-Americans. The calamitous arrival of Mormon pioneers led to a range of emotions for the Southern Paiute, but still, they hoped to live peacefully among these new settlers and even other bands of Indians if it meant keeping their land.

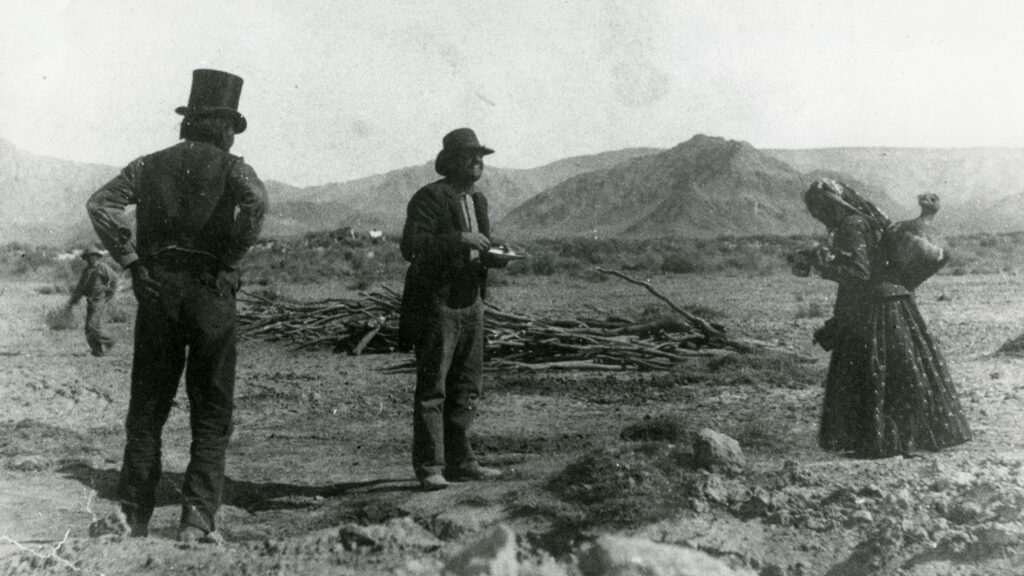

While 400 Native Americans lived in the Moapa Valley at the time of their (and Longstreet’s arrival), it was proposed that 2,300 people could relocate to the region under the promise of maintaining control of their ancestral homelands. Yet, the settlers argued that they’d already gone to elaborate lengths to create an irrigation system and somehow proved that the land was more fertile under their colonization to try and maintain control over “their” newly claimed territory. On top of it, the Southern Paiute were treated as uncivilized people who basically wouldn’t know what to do with the land if they did maintain control, and were ultimately “bought out” for an extremely depressing 32 thousand dollars.

To make matters worse, the land they were promised—the Moapa Valley Indian Reservation—was not only largely reduced in size by the time the deal was actually inked, but of course the Southern Paiute were pushed to the least desirable acreage, like the quicksands of the Virgin River. Additionally, their farmlands operated on a dismal water supply from the dumb dumb pioneers, Mormon-driven cattle mowed down any crops they could actually get to grow in infertile swaths of land, and their game was overhunted. Like most of the other (smart!) white men during this era, Longstreet listened and learned from the Southern Paiute until he spoke the language of the Nuwuvi as if he were one of them, learning it was impossible to ignore the many wrongdoings against them.

While listening to and recording many grievances, Longstreet initially operated a tent saloon-style drugstore upon his arrival to St. Thomas, but that didn’t last long. He wasn’t actually a doctor and didn’t have any formal medical training, and that timed out badly when everyone in the valley got super sick and he wasn’t equipped to actually treat them. So, he sold his setup, and purchased 120 acres of land 60 miles due north of the Moapa Valley Indian Reservation and from what I’ve read, didn’t take any shit from these absurd Mormon pioneers terrorizing his Southern Paiute pals.

He eventually grew his 120 acres to 240 over the course of about ten years, and along the way, shot at least one guy in an “accident” nobody could ever really explain. The guy was personally responsible for allowing his cattle to trample Indian crops and basically being an all-around jerk, and then suddenly and very mysteriously ended up dead in a ditch after being around Longstreet. His cause of death was ruled as exposure even though a few people who saw the body claimed there were three bullet holes in him. With no witnesses, Longstreet got off.

Things continued to go from bad to worse with awful Indian agents not doing their jobs. All the government-funded infrastructure promised to them on the Moapa Indian Reservation never came to fruition, clothing and blankets designed to be delivered to them were sold off, they were charged for seeds, tools, and other supplies that were supposed to given to them for free, and were essentially required to pay a toll on land that already belonged to them.

There was also a really complicated string of events where Longstreet exposed many wrongdoings committed against the Southern Paiute by a particular Bureau of Indian Affairs-appointed Indian Agent. And this dude lived up to every syllable of a truly villainous name: Colonel Farmer Bradfute. Barf. He did a lot of bad things and Longstreet basically called him on all of them, to the point where Colonel Bradfute tried to unveil Longstreet’s outlaw background in hopes of having him locked up for good. But it didn’t work, because with no actual proof and a few unbelievable character witnesses he remained free, including one from Christian Zabriskie (yep, that Zabriskie), who defended Longstreet with a story about when he saved him from being stranded in the middle Death Valley by shoeing his horses when he was stranded 200 miles from the nearest blacksmith.

And despite baseless, convenient accusations against him when he got in the way of powerful people’s unethical decisions, that is exactly the type of guy Longstreet was. He’d already spent decades doing risky things few others were willing to do. Where there was a killer he tracked them in terrain where lawmen were even afraid to go. He made sign posts to save lives in desolate stretches of desert that three white men knew well enough to mark, navigated unmapped places as if he’d already been there, and continued to engage with Indians in their own language and more importantly, defended them.

But, with all of Bradfute’s baseless threats pushing him out of Moapa Valley, he would return long enough to see proper Indian Reservation boundary fences built and wrongs righted. It wasn’t long after that when he basically immediately sold his ranch, and headed West into wilder country to the headwaters of the Amargosa River in Oasis Valley.

Into Sylvania, and an Unexplored Desert

We know this part of Nevada as Beatty today, but back in the 1870s when Longstreet rode into this stretch of desolate desert, there were only three white men living in this part of the world. Longstreet was one of them. Right on the outskirts of Death Valley National Park, this section of “Unexplored Desert” became known as Oasis Valley because it was the first glimpse of water in a diresome 42 mile stretch of arid terrain without any. Longstreet settled into this uncharacteristically lush valley on a 160 acre homestead at the headwaters of the Amargosa River, which flows 185 miles mostly underground as one of the world’s longest, and complex rivers from Beatty, all the way down to Ash Meadows.

Longstreet was in his fifties when he arrived in Oasis Valley, and would stay here until he was well into his seventies running another tent saloon, this one rowdier than any others ahead of it. In other words, Longstreet’s gun barrel made its point more than a few times during these two decades of his life. He had proven not only his tastes for isolation ran as far and wide as the Amargosa, but so did his unrivaled survival skills in places so remote even the Natives avoided them.

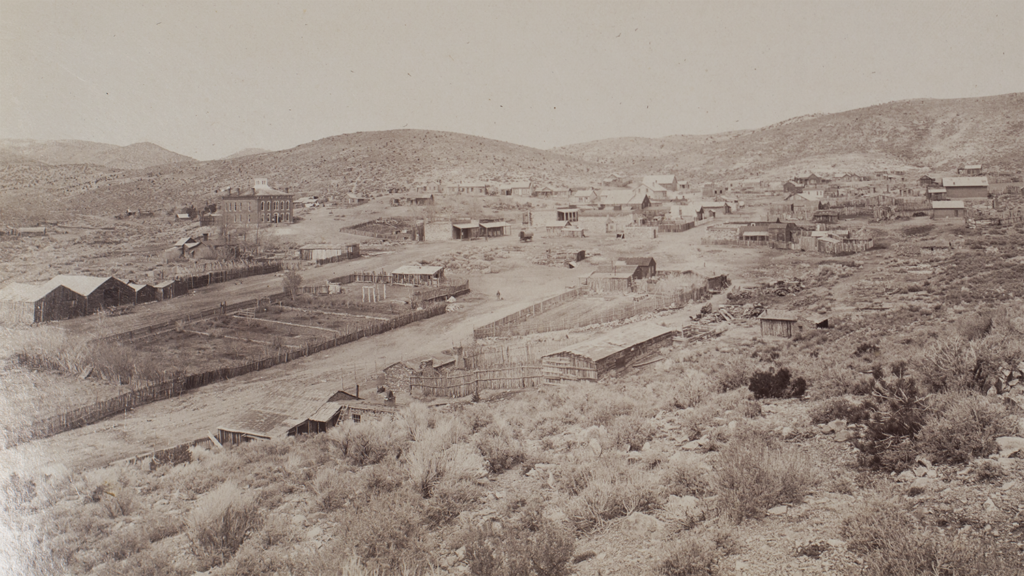

By 1890, ten years ahead of the Tonopah and Goldfield mega-bonanzas that would draw populations this central section of Nevada had never imagined, he left Oasis Valley for an up-and-coming mining camp called Sylvania. Situated right along the modern-day California-Nevada border near where Fish Lake Valley is today, lead and silver deposits were discovered here, and ma ybe what’s most fascinating to me is that even though there were plenty of far livelier and prosperous mining camps nearby, he chose Sylvania as his next, brief home because it was the type of place where an outcast could be accepted with no questions.

Unlike the Virginia Citys and Bodies of the world, Sylvania was not civilized or wealthy and that’s exactly why he steered his cayuse in that very direction. It didn’t have fancy opera houses, ornate churches and homes, and definitely no well-dressed millionaires discussing the success of their investments, but in its place a small, hopeful, and uproarious population on the edge of the known world. What a romantic vision that must’ve been.

His time in Sylvania was again earmarked by standing up for the Paiutes, who had for the most part accepted him as one of them, asking him what land he belonged to and not the name of his tribe. He fought for the many Paiute miners who were not being paid at the Sylvania Mining Company, or being paid at very unfair, discounted rates. His friendship and natural instinct to defend Native Americans was something that didn’t exist in the time he was alive. But what’s even more rare, or at least a story you didn’t hear happening much back then, is that Longstreet participated in many sacred rituals with Wovoka, the messiah of the Walker River and creator of the Ghost Dance.

There’s enough info and intrigue about the Indian Ghost Dance movement to have an entire story about it, but for the sake brevity in this one, it was essentially an entire spiritual movement that began in Nevada in 1889 when a Paiute named Wovoka prophesied the extinction of white people and the return of the old-time life and superiority of the Indians. It’s a social dance, but also considered a healing practice, and Longstreet participated in many of them in the Walker River region, and mind bogglingly, right alongside Wovoka himself.

Ash Meadows, and more legendary frontiersmen-in-the-making

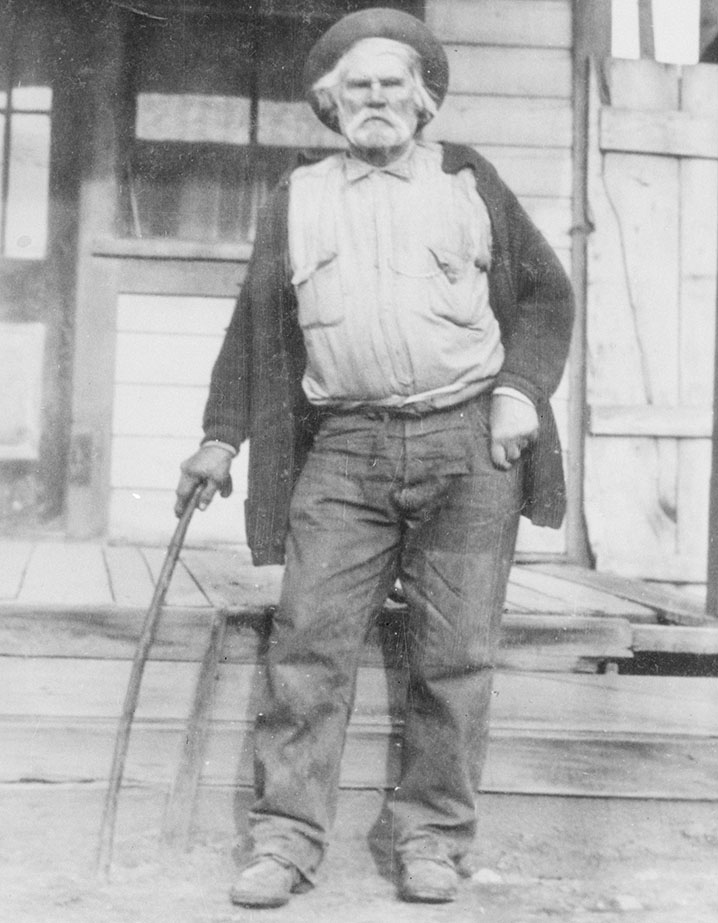

Most of the places Jack Longstreet lived and even traveled through weren’t established places then, or even now, and even if he did live with some sort of permanence, most of his old homesteads were lost to time long ago. That is, with one exception: Ash Meadows.

Today, some of us know Ash Meadows as Nevada’s tiny piece of Death Valley National Park — a national wildlife refuge that beholds crystal-clear, icy-blue pools with an almost unbelievable vibrancy that behold silvery flashes from the world’s rarest fish. And just like everywhere else in the West, it originally belonged to the Southern Paiute (the Timbisha), though its English name was decided upon because of the thick groves of ash trees that once stood there. With a collection of gushing, Amargosa River-fed pools you’d never know were there unless you actually stopped by, Ash Meadows became the perfect hideout for Jack Longstreet, where he could continue living in secrecy while also advocating for wrongdoings made against the Timbisha people who’d spent many generations there.

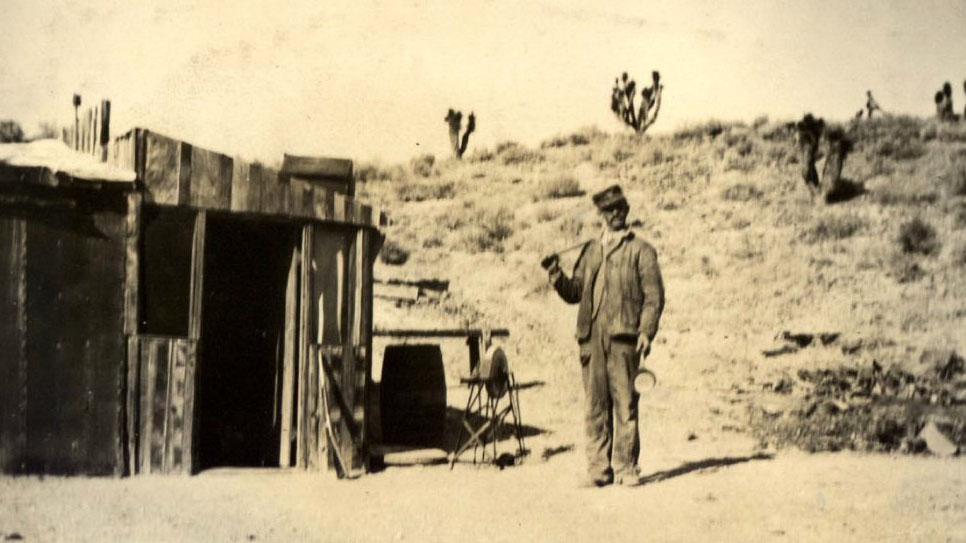

So Longstreet squatted on the land among the Paiutes, built a small cabin near an absolutely unreal natural warm spring, and named it Ash Meadows Ranch. Even though this was one of his shortest, permanent stints as he roamed from one isolated Nevada location to the next, it’s his only residence that became permanent, and also monumentalized once the Death Valley National Park boundary line absorbed this historic site. Despite having sat there for more than 100 years and almost reclaimed by the Mojave Desert entirely, funds from a $90,000 grant from the Nevada Public Land Management Act restored Longstreet’s cabin in 2004. There’s that, and of course the wild-ass Longstreet Inn & Casino, which is a must-experience if you’re ever passing through, if only to give Jackpot the bar cat a scratch on the head from me.

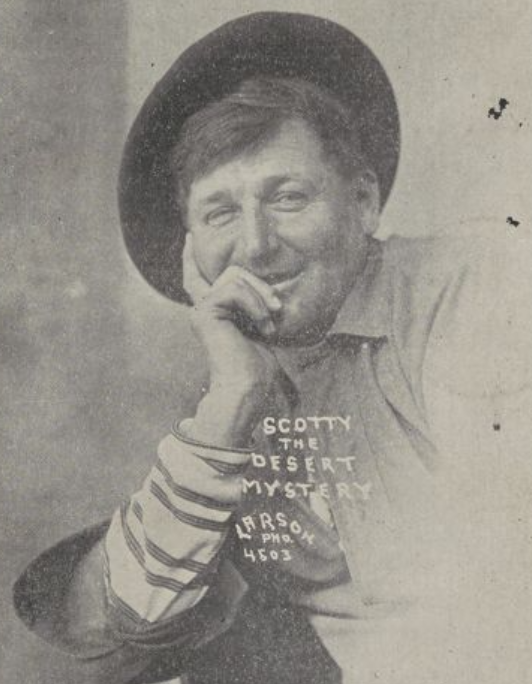

All of Longstreet’s time in Nevada and northern Arizona Territory was special and meaningful, but his time in Ash Meadows really lights up all the corners of my imagination, and mostly because of the people he was running around with in this region. Some of them included Christian Zabriskie, who would become rich from borax operations in the Death Valley and Candelaria regions, Death Valley Scotty, who was basically another Western frontiersmen who ran around with Buffalo Bill and would guide people through a wild and dangerous Death Valley, Shorty Harris, who discovered bullfrog-shaped nuggets of gold in the Bullfrog Mining District which would become Rhyolite and dozens more mining camps, and Shotgun Kitty, who was a hotel cook, poker player, and expert markswoman.

Ash Meadows is also where Jack would meet his Southern Paiute wife Fannie Black. And despite having already lived a full life by this point and setting himself up to hunker down in Ash Meadows for the rest of his days, the intrigue of an even more isolated frontier called him deeper into the Nevada desert.

A Death as Mysterious as His Life

Jack and Fannie sold their Ash Meadows property for a piece of paradise in central Nevada’s Monitor Valley—or just up the road from what we know today as Belmont Ghost Town. He would live out his last days (into his nineties) like the last eight decades that preceded them, fighting for the excitement of it, hunting and exploring as it pleased him, dancing on mountain tops, and embracing the freedom of the old frontier—or the exact version I can’t get ever seem to get out of my imagination.

His demise was just as much of a mystery as the rest of his life, where he would accidentally shoot himself in the armpit or shoulder, then ultimately die from it at the age of 94. Even though he went to the hospital in Tonopah (which had boomed by then), he left early, it became infected, and he would suffer from a stroke. Longstreet’s dire condition was discovered when a friend rode to his ranch to find him unable to move, and lying alone in the intense heat without any water. Fannie was around somewhere but not at his bedside, which some say could’ve been related to her Paiute beliefs of when a man grows old and helpless it’s better off to let him die. Jack was hurriedly taken to Tonopah and a car was dispatched to bring Fannie to the hospital, but Longstreet died before she could arrive, and while Longstreet died in 1928, a much younger Fannie was only 4 years behind him. They were both buried next to each other in the Belmont Cemetery.

A hero by some and a criminal to others, Longstreet outlived most of his admirers and enemies alike. His self-reliance, leadership, and allegiance to doing the right thing when it cost him everything is something to celebrate every time you head out into Nevada’s big ol’ big empty in search of isolation—I know it is for me. To be a misunderstood person among a miscast place is a trait I think all of Nevada’s most interesting explorers share in common—at least that sure was the case with ol’ Longstreet, who led a life so intriguing it perpetuated a century-and-a-half of frontier myths that all turned out to be true.

Sources

- Allen Metscher (Director of the Central Nevada Museum) in discussion with the author, February 2024.

- “Christian B. Zabriskie”, Death Valley National Park/National Park Service, February 2024, https://www.nps.gov/deva/learn/historyculture/christian-brevoort-zabriskie.htm

- “Death Valley Scotty”, Death Valley National Park/National Park Service, February 2024, https://www.nps.gov/deva/learn/historyculture/death-valley-scotty.htm

- “Jack Longstreet”, The Historical Marker Database, October 29, 2021. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=107098

- Jack Longstreet: A Nevada Frontier Character”, Miscellaneous Ramblings of a Happy Wanderer, May 14, 2012. https://sam-miscellaneousramblings.blogspot.com/2012/05/jack-longstreet-nevada-frontier.html

- “Nye County History”, February 2024. http://nyecountyhistory.com/cem/longstreet.pdf

- Zanjani, Sally. 1988. Jack Longstreet: Last of the Desert Frontiersmen. Las Vegas, NV. Nevada Publications.